In 1928, a strange phenomenon was sweeping the state of Idaho. A Boise resident might wake up on a typical Monday morning, drag themself out of bed, and they would hop in their car to drive to work, only to realize that their license plate had been stolen right off of their car. “People would come up but they would pull up to either a tourist park or a motel and they would spot those plates and […] they would just take it off of the car,” says historian Rick Just.

People just couldn’t resist. Because that year, Idaho had revolutionized license plate design. Before this, license plates mostly only displayed basic information like the state name and the registration numbers on a solid-colored background. But in 1928, the secretary of state in Idaho had an epiphany. He realized that the license plate was the perfect place to advertise a home-grown product, and that product was… a potato. The execution wasn’t perfect. But it was innovative. Below the tremendous tater, there was even a modest, pragmatic slogan: Idaho Potatoes.

Idaho was the first state to slap a slogan on a license plate, which may not seem like a big deal, but it turns out this idea would end up having outsized consequences, and not just for Idaho. Because what started in one state would soon spread. And when it did, the question of what should go on a license plate, and what shouldn’t, would prove surprisingly contentious.

The Call of the Road

The first state-issued license plates appeared at the very beginning of the 20th century, and they served a mostly bureaucratic function. More people were buying and crashing cars every year, so state governments originally mandated plates as a way to keep track of all the nuts behind the wheel. No one was interested in sloganeering… but then, Americans discovered the great American road trip.

Christine Byron is a former history librarian and worked at the Grand Rapids Public Library and she says that the rise of the road trip in the 1920s created a huge new tourist market. People on the road needed services that hadn’t existed in the age of steam-powered travel. Gas stations, food, roadside motels — from the states’ perspectives, all those new tourist dollars were up for grabs. States began letting the world know what they had to offer. Arizona had the Grand Canyon. Minnesota had its lakes. In this war for tourists, states promoted themselves anywhere they could, but no one thought to advertise on a license plate until 1928 when Idahoans realized that their plates were too valuable to waste on just a registration number.

Idaho’s potato plates centered on agriculture, rather than tourism. But still, Rick Just says once Idaho staked its “starchy flag” on the license plate, the rush was on. “License plates became a different thing because of that potato.” States spent the middle of the century transforming their plates from austere government documents into colorful boosters of tourism and industry. In 1940, Arizona stamped “Grand Canyon State” on its plates and never looked back. In 1950 Minnesota went with ‘Land of 10,000 Lakes.” Some states went with a classic slogan and stuck with it, like New York’s “Empire State.” Other states couldn’t make up their minds.

As fun as some of these plates might have been, at half a square foot, a license plate is a small canvas. When you have to pigeonhole an entire state into a single idea, not everyone is going to be pleased. Florida had to nix one of its plate designs after residents complained that the grapefruit with a stem attached looked more like a bomb. Massachusetts, meanwhile, tried to put a codfish on its plate only to be blamed by fishermen for a poor catch that year because the fish on the plate was swimming away from the word “Massachusetts.” But the fight over license plates was about to be taken to the next level, thanks to a politician named Meldrim Thomson.

Thomson was a titan of New Hampshire politics in the 1970s. He served three terms as governor and he was a conservative firebrand who hated democrats. Thomson had a lot of unorthodox ideas (including wanting to arm the New Hampshire national guard with nuclear weapons) and he was obsessed with the idea of “freedom.”

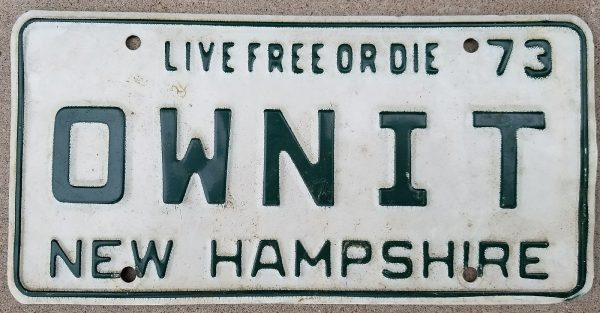

“Live Free or Die,” of course, is New Hampshire’s fiery state motto. It was coined by a Revolutionary War vet, and Thomson loved it so much that, before he became governor, he worked with allies in the state legislature to get it slapped on every car in the state. In 1971, the slogan on the state’s license plate changed from Scenic New Hampshire, to Live Free or Die.

Live Free or… Go to Jail

Not everyone embraced the “Live Free or Die” slogan. At 88 years old, George Maynard still gets heated about the New Hampshire license plate. Maynard and his family joined the Jehovah’s Witnesses, and in 1972 they moved to Claremont, New Hampshire. That’s where the trouble started.

Every day, Maynard would hop in his car to drive to work while his New Hampshire license plates displayed in all caps, “Live Free or Die.” This really grated on Maynard because he didn’t share Meldrim Thomson’s belief in freedom over everything. As a Jehovah’s Witness, Maynard actually believed that God-given life was more important than freedom and he didn’t appreciate the government telling him what to die over. So Maynard covered the slogan up with some tape. But when he erased the state’s message, George Maynard marched to the front lines of the license plate wars.

Covering up the slogan was a violation of state law, and one day Maynard and his wife were coming back to their car after doing some shopping, and they saw a police officer writing them a ticket. Maynard refused to pay the $25 ticket and also kept the tape over the slogan. The tickets piled up. Finally, his consistent refusal to pay them landed him in court. The judge ended up putting him in jail for fifteen days, “And so if you don’t want to live free or die, you go to jail in New Hampshire,” says Maynard.

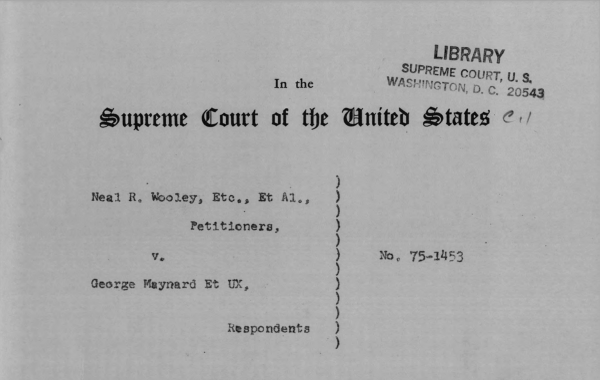

But Maynard still wasn’t done fighting. With the help of the American Civil Liberties Union, he filed suit in New Hampshire, claiming the state’s law prohibiting the altering of license plates was unconstitutional. The state court agreed but unfortunately for Maynard, Meldrim “Live-free-or-die” Thomson, had become governor by then, and he appealed the case all the way to the Supreme Court. License plates collided with the First Amendment before the high court in November of 1976. During oral arguments, George Maynard’s lawyer claimed that, in covering up Live Free or Die, George was just exercising his freedom of expression. The Supreme Court ultimately ended up siding with Maynard. “The First Amendment protects [..] you against government censorship. But the free speech clause also protects your right not to speak,” says Caroline Mala Corbin, a First Amendment scholar at the University of Miami, “So it protects you against the government, forcing you to say an ideological message that you disagree with. And that was what the problem was here.”

Another Plate, Another Battle

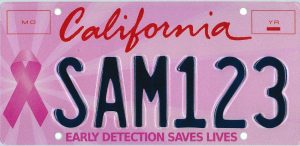

As it turns out, the constitutional battle over license plates was not over because after all of that was settled, a new problem showed up: specialty plates. Unlike vanity plates, where drivers choose their own numbers, specialty plates sport alternate designs with their own logos and slogans. They’re usually put out in collaboration with the government by a non-governmental organization. When drivers choose a specialty plate, they pay a little extra and those proceeds get split between their chosen group and the state Department of Motor Vehicles.

Specialty plates are easy money and a lot of states will issue one to almost any group as long as enough people are interested. But the problem with an open-door policy is you might not like who comes inside, and about a decade ago, the state of Texas learned this the hard way. The DMV board votes on proposed designs for specialty plates and one particular year The Sons of Confederate Veterans wanted Texas to issue a license plate featuring the Confederate battle flag.

In favor of the confederate flag plates was Jerry Patterson, Commissioner of the Texas Land Office and a member of the Sons of Confederate Veterans and Patterson made a First Amendment argument. He thought that if enough people like him wanted a specialty plate related to Texas history, the state shouldn’t be allowed to prevent them from having it. After two hours of tense testimony, the board held its vote and rejected the Confederate flag plates. But then the Sons of Confederate Veterans sued, arguing that the state was unfairly singling out The Sons of Confederate Veterans when it denied their plate.

I’ll See You In Court… Again.

So in 2015, license plates were back in the Supreme Court. George Maynard’s “Live Free Or Die” case had established that you could reject the state’s messaging if it didn’t suit you. But was it okay for the state to reject your message on a state-issued license plate? This time it was a really close decision—a 5-4 split. But the court’s majority sided with Texas. The state could deny the confederate flag plates. The court acknowledged Jerry Patterson’s right to display symbols—even abhorrent ones—on a bumper sticker, but they said that right does not extend to license plates, because the court held that specialty license plates were government speech—and the government’s right to speak is also protected.

Ultimately, the Supreme Court’s decision in George Maynard’s case didn’t resolve all the issues around license plates. And neither will the Texas decision. Caroline Mala Corbin thinks license plates will always be a contested space—a government-issued document, displayed on a private vehicle. It’s as if a license plate is a kind of bullhorn. Only instead of taking turns speaking, both the government and private individuals are trying to speak into it at the same time. Perhaps that’s why this little hunk of metal has so often become an ideological battleground, a place for governments and citizens to clash over the identity of an entire state, in the attempt to reduce it to a slogan and symbol, speeding down the highway.

And those debates are still playing out. The supreme court ruling empowered Texas to keep the confederate battle flag off its license plates. But it also empowered states to make the opposite choice and at least six have. If you live in South Carolina, Mississippi, Alabama, Louisiana, Georgia or Tennessee, you can go to your local DMV today and register your car with a state-issued plate bearing the Confederate battle flag. In a couple of those states—Tennessee and South Carolina—lawmakers have actually introduced bills that would ban the flag from specialty plates… But so far and neither bill has gotten a vote.

Comments (16)

Share

NWT license plate is my favourite.

North West Territories! Absolutely!

I immediately thought about the Northwest Territories when listening to this episode.

The best current license plate design is hands down, the license plate for the Northwest Territories in Canada.

Any thoughts on the safety implications of these different designs? Some of them (such as the California state parks one) don’t look as though they’d be very clear and legible from a distance.

Personally, my favourite registration plates are the ones from Switzerland. They have the Swiss flag in the form of a shield on one side, the 2 letter cantonal code followed by the reg. number lastly flanked by the cantonal flag in shield form.

They aren’t too busy, are easy to read and pleasing to the eye.

Absolutely! When I visited Switzerland, I couldn’t stop staring at those plates. They’re such a delightful design.

Canada’s Arctic has the best plates. Northwest Territories has is polar bear plates, Yukon Territory has a prospect panhandling, and Nunavut has the territory’s name in both English and Inuktitut. Nunavut also had a polar bear shaped plate as well.

How could you not discuss Delaware plates and why they are so generic? There’s a reason they aren’t like the other states’.

And that there is a “market” for low digit plates. After the license digit 3 – they can be had via tag switching. Often down a family tree – my father won his in a poker game from his brother after my grandfather passed away and before the plates had “value”. Single digit plates can be quite valuable and also can be considered part of an estate and be valued and taxed!

The NWT plates are nice, but the new Nunavut plates are disappointing. The Yukon plate is distinctive, but a bit kitsch. Nunavut has one of the BEST designed flags in all of North America, and a perfect candidate for a license plate, so it’s sad that they didn’t use it.

BC’s plate is simple, but the serif font is grating. The personalized plates in BC are nice, the BC parks plates are horrid. The Vancouver 2010 Olympic plate was horrible but not as vomit-worty as the BC Parks plates.

Alberta’s plate really has an understated beauty and fascinating typeface, and shout outs to Quebec as well.

I wish the D.C. plate and it’s complaint in resistance against the federal government, “Taxation Without Representation” was mentioned. It’s definitely the most clever use of a license plate that I’ve ever seen.

Here is the most creative license plate collection I’ve seen

https://americanart.si.edu/artwork/preamble-27722

This episode reminded me of all the controversy around the new Ontario license plate. There was controversy around them every step of the design process…

Before the design even came out, there was criticism over the proposed slogan change. The premier (head of the province) wanted to change it to one of his political slogans, “Open For Business.” People thought it was tacky, and the premier settled on using it for commercial plates only.

Then when the design was revealed, the blue text on white of the previous design was replaced with a blue on blue design. People called it a political move, since it doubled down on the premiers political party colour (blue). This didn’t pair well with the redesign being seen as a political move in the first place.

However, that issue didn’t matter in the end, because when the plates were rolled out anyways, they had a bigger problem: the numbers become invisible at night. An office duty police officer posted a photo of the plates at nights, most people couldn’t read the numbers on them, and the topic went viral through the province. There is now a recall and a redesign going on, but when this issue was sidelined a month later by the pandemic, the process slowed down.

Was hoping to see more of the collection from the coda!

I too would have loved to hear a coda on the Delaware aftermarket for low digit plates. It was an interesting discussion in the family after my grandmother passed and the different dollar values for her cherished tags. I say cherished, because that was a bragging point for her for years.