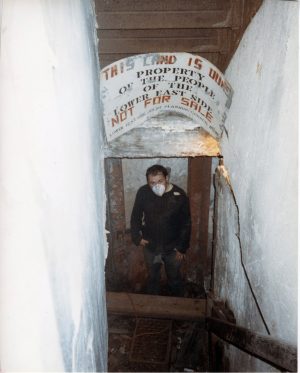

In 1987, three years after moving to New York City, Maggie Wrigley found herself on the edge of homelessness. She was trying to figure out where to stay, when she heard about an abandoned tenement building on the Lower East Side. It was owned by the city, but it had been left empty and unmaintained. The building was full of rubble. Some of the walls were rotten and falling down. There was no running water. But it was a place to live, rent-free. Wrigley moved in.

It wasn’t just the building that was falling down. The whole Lower East Side — a neighborhood that today is filled with expensive boutiques and high-end condos — was struggling in the 1980s. There were trash-strewn lots and empty buildings everywhere. By the late 1980s, squatters like Wrigley would come to occupy more than a dozen old tenements on the Lower East Side.

These squatters would eventually do something improbable: they’d resist eviction by the city for almost two decades, even as the neighborhood around them gentrified, and as the buildings they occupied became more valuable, and as the city tried harder and harder to kick them out.

In the 1960s and 70s, New York City began to hollow out. The city lost many of its manufacturing jobs, and people with means moved to the suburbs. The city’s tax base declined, and in many neighborhoods, property values started to slide.

During this period, some landlords began “milking” their properties. This meant they’d do all they could to extract maximum profit from them. They’d neglect upkeep and cut services while still continuing to collect rents. And when the money coming in from rents no longer covered the cost of a mortgage or property taxes, some landlords would just walk away. In lieu of collecting back taxes, the city ended up taking ownership of tens of thousands of poorly-maintained properties.

The New York City government was also struggling financially at this time, and it began to cut off services to some parts of the city. This was an intentional strategy called “planned shrinkage.” The city closed fire stations in poor neighborhoods, withdrew services, and made few repairs on public infrastructure. Neighborhoods across the city — like the Lower East Side — ended up largely depopulated and full of abandoned buildings. All of which meant terrible housing conditions for the people who remained, but lots of opportunities for squatters.

The squatters included an eclectic mix of artists, punks, transients, displaced locals, and political activists. There were some residents with mental health issues and addiction problems. Many of the squatters also saw themselves as activists for affordable, or free, housing in a city that was plagued by homelessness.

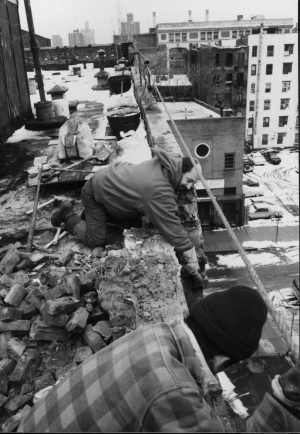

The squatters set about fixing up their decrepit buildings, clearing rubble, building stairs, reinforcing walls, and replacing windows. They tapped into the city’s electric grid and water system. From the early- to mid-80s, the squatters didn’t face much active resistance from the city, even though they were illegally occupying city-owned buildings.

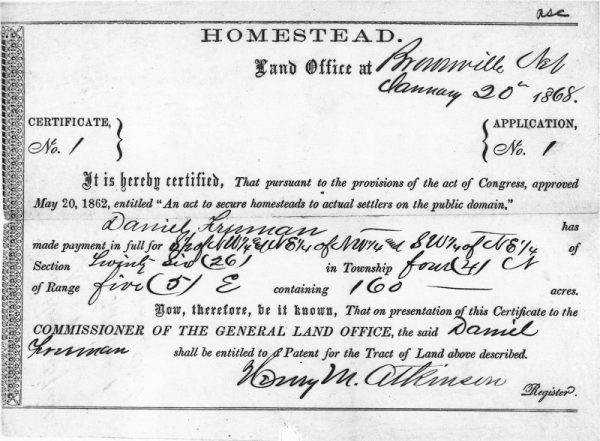

When the squatters took over the buildings on the Lower East Side, they were part of a long American tradition of laying claim to land by occupying and developing it. In 1862, Congress passed the Homestead Act, which opened up millions of acres of land in the American west to settlers. They had to farm it and improve it, and then after five years, they could take legal ownership.

By the 1970s, the idea of urban homesteading had taken hold in cities. Local governments would offer cheap or free houses to low-income residents, provided they worked on the buildings and brought them up to code. Many squatters saw themselves as engaged in a similar effort, but outside of any officially sanctioned program.

In the late 1980s, New York City turned a corner and began coming out of a decades-long economic slump. People were moving back to the city, real estate prices had started to climb, and the city began to reinvest in neighborhoods it had long neglected. But this upward economic pressure meant trouble for squatters. Now they had to fight to hang onto whatever spaces they had claimed.

A lot of the tension focused on Tompkins Square Park on the Lower East Side. The park was close to many of the squats and the site of homeless encampments. In the summer of 1988, the New York Police Department implemented a 1AM curfew, hoping to reduce the number of people living and sleeping there. The curfew sparked protests, which turned into riots. Many of the squatters were part of the altercations.

The city wanted the squatters out of the neighborhood. Local politicians — and some other affordable housing activists — accused the squatters of using renegade methods and of occupying buildings that were badly needed by other low-income residents who had deeper roots in the neighborhood.

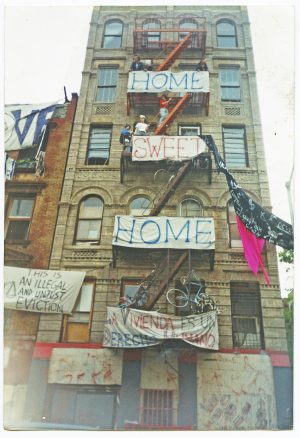

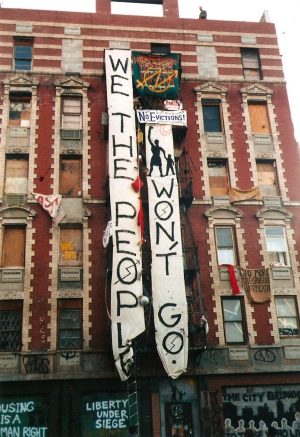

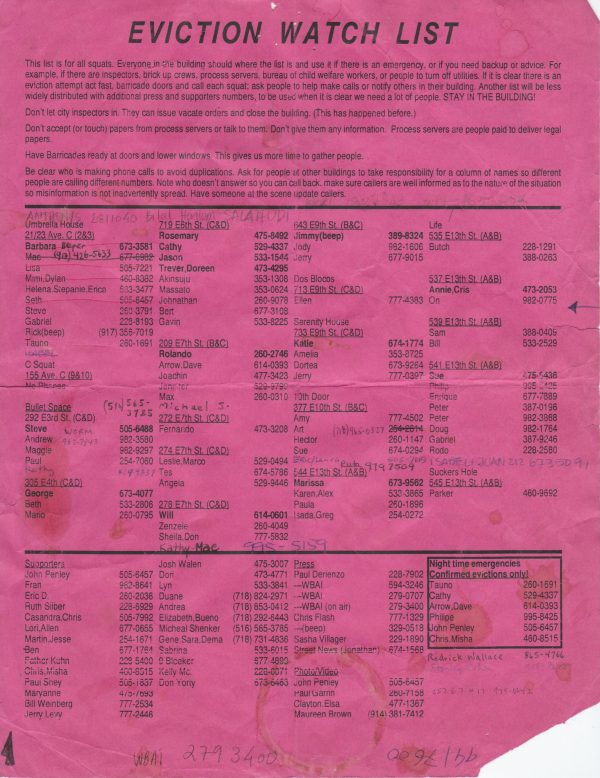

As criticism mounted, the city pushed to evict the squatters. In response, the squatters fought back. They organized an Eviction Watch List, and would block police from entering their buildings. Sometimes they’d defend the buildings from inside, throwing paint and garbage down on the police — or buckets of urine.

The squatters weren’t just fighting the city in the streets. When a number of their buildings were slated for redevelopment, they also began devising a legal strategy, using “adverse possession law.” State laws vary, but in New York this laws says that if you occupy a piece of property for ten years — openly, notoriously, continuously, and exclusively — and the person who legally owns that property doesn’t force you out, you can claim title to that property.

Some of the squatters were wary about getting tangled up with the legal system, but others saw adverse possession as a chance to gain ownership. The squatters began building a case and presented their claim to a well-known liberal judge named Elliott Wilk. The judge found the squatters were likely to make a successful case against the city and granted them an injunction against eviction until the case was decided. But before the case could be settled in court, and despite the injunction, the city evicted the residents of two of the buildings. City inspectors claimed they were in danger of collapse.

These evictions provoked the biggest showdown yet between the city and the squatters. On May 30, 1995, the city sent a small battalion of police in riot gear to the Lower East Side. They had a tank repurposed from the Korean War. Officers took up positions on the rooftops of neighboring buildings. Meanwhile, the squatters welded bicycle frames to their fire escapes so it would be difficult for firefighters to climb them. They poured tar on the street, so police would have to march through it as they approached the buildings.

The police presence went on for months. Officers sealed off the ends of the block and required people to show ID before they’d let them through. Still the squatters wouldn’t give up.

Rudy Giuliani, mayor of New York City at this time, was a vocal critic of the squatters. But astonishingly, in 1999, a secret negotiation between the city and the squatters started to unfold. They began to discuss what had once seemed impossible: legalization. The city would sell the squatter’s buildings to a third party, a non-profit organization called the Urban Homesteading Assistance Board. UHAB would then turn the buildings over to the squatters and help them get loans so they could bring the buildings up to code.

After years of negotiation, the deal went through in 2002 — the city sold eleven buildings to UHAB, for one dollar each. And UHAB began working with the squatters to turn their buildings from squats into limited-equity, low-income co-ops. “Limited-equity” meant there would be a cap on how much the apartments could be sold for.

As the squatters rehabbed the buildings and brought them up to code, some of the more unique, hand-built elements of people’s apartments had to go. Some of the buildings became less wild, more uniform. Fewer hand-made mosaics, more boring drywall.

There have been hard trade-offs along the way, but for many, like Maggie Wrigley, the legalization has been a victory for affordable housing in one of the most expensive cities in the country. And it represents a kind of stability at the end of nearly two decades of drama. Maggie’s building is still full of artists and activists. Some people are having kids and starting families.

Maggie’s not a squatter anymore. She’s something else. A homeowner.

Comments (5)

Share

We’re not gonna pay, we’re not gonna pay, we’re not gonna pay LAST YEAR’S REEEEENT!!!!

You can see some footage of the 1995 era in Allen Ginsberg’s documentary, he goes and visits one of the buildings with the camera crew.

I can’t believe that the musical Rent wasn’t referenced once in the piece.

Very interesting episode, also useful to understand shows like “The Get Down”, even if it’s set in the late seventies.

I slightly regret that the opposition between the other poor people in the neighbourhood, who presumably continue to pay their taxes in a completely derelict place, and what they call “Yuppies Squatters”, has been quite overlooked. One feels that this episode almost only describes the “good” squatters against the “bad” city & gouvernment, when it seemed to be actually more nuanced.

As a longtime Buffalo real estate attorney, I often advise clients who buy an “abandoned” building to give any squatters permission to remain on the premises until they are ready to actually use it or sell it. Squatters often take better care of their places than actual tenants, making sure the building is secure and that the infrastructure remains usable. Also, granting permission can inoculate the new owner against an adverse possession claim by taking away the element of hostility. When it comes time for the squatters to go, I also recommend paying the squatters back for any improvements they have made.