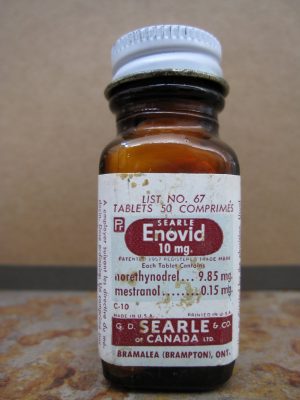

In 1960, a new wonder drug hit the U.S. market. And while lots of new drugs promise dramatic results, this one would actually transform millions of lives and radically shift American culture. It was called Enovid. It was the first oral contraceptive, and it ushered in extraordinary changes and opportunities for women.

Within just two years, 1.2 million American women were taking the birth control pill. Within five years, the pill would become the most popular form of birth control in the United States.

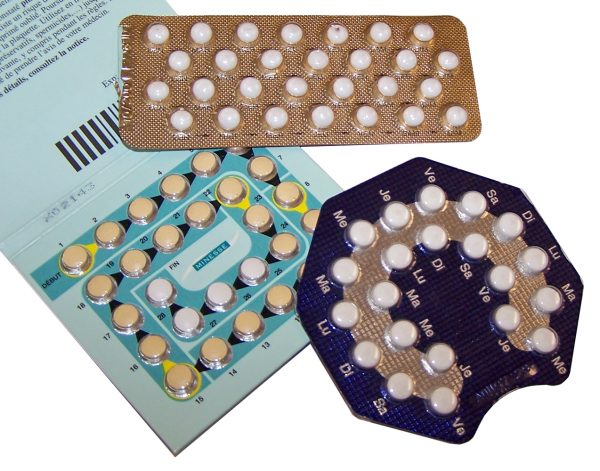

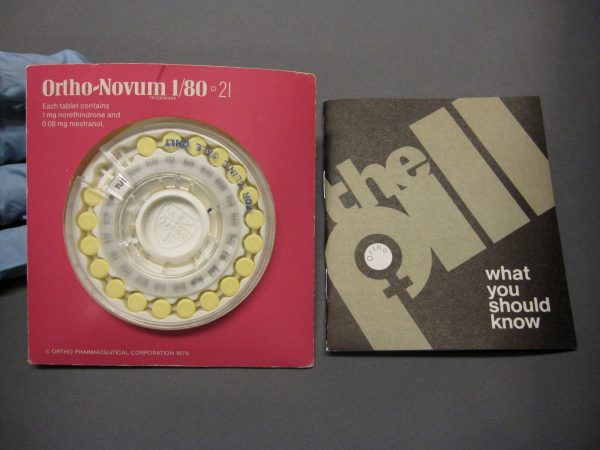

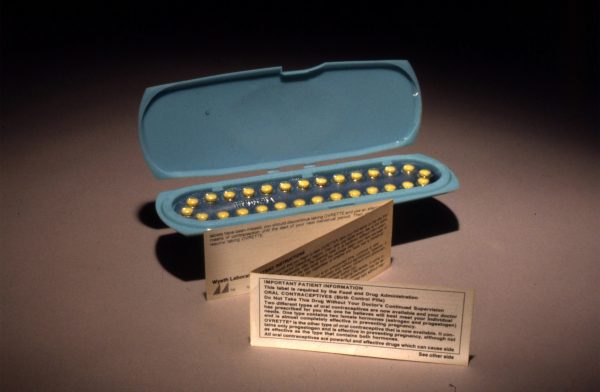

Most people are familiar with at least one version of its packaging — a round plastic disc which opens like a shell and looks like a makeup compact. But the pill wasn’t always packaged this way. The first birth control pill to hit the market came in a simple glass bottle of loose tablets, like any other prescription pill.

How the pill traveled from these nondescript bottles into some of the most heavily designed and recognizable pill packages in history, tells a story about the medical and cultural anxieties of the time. And it begins with a family in Illinois.

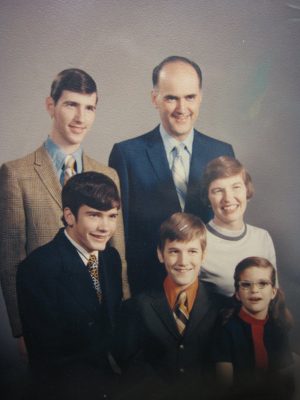

In 1961, David and Doris Wagner were a middle-aged couple with four kids. They didn’t want more children, so they were thrilled to learn about the pill. Doris got a prescription. The pills came in a big glass bottle. The instructions said to begin the pill on the fifth day of her period, and to take one pill every day for twenty days, followed by a five day break for menstruation.

If Doris lost track of her cycle, or if she forgot whether or not she had taken her pill that day, she was instructed to pour all the pills out of the bottle, count how many pills were left, subtract that by the original number of pills, and consult a calendar. Not a very user-friendly design.

If Doris missed a pill, she risked getting pregnant again. That made both Doris and husband David very nervous.

David Wagner was an engineer and used to solving mechanical problems. He figured he could create a packaging system that would make the pill-taking process easier. First, he created a simple calendar on a piece of paper and placed each pill on the correct day.

That worked pretty well, until the inevitable accident, when the pills were scattered and fell to the floor. What David Wagner came up with next is very similar to what is still used today.

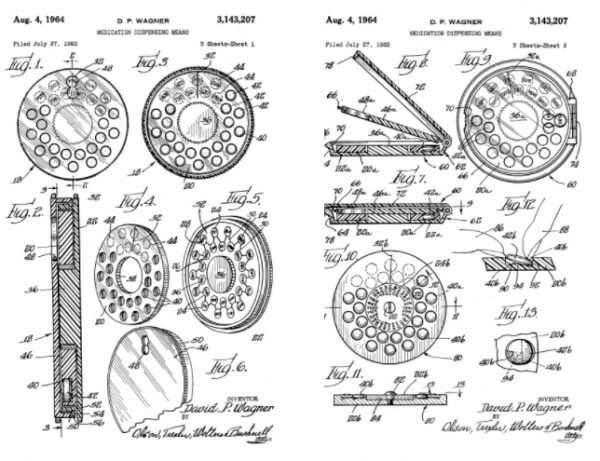

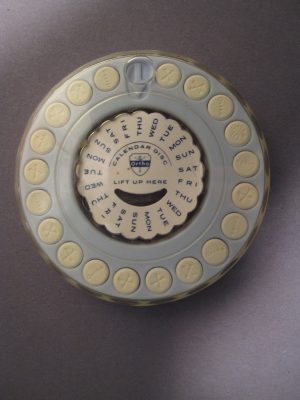

Wagner’s original prototype was made out of two disks of clear plastic and a snap fastener he borrowed from his child’s toy. The bottom disk held twenty pills. The top disk had one hole drilled through it, which could be rotated each day to expose the correct pill along with the corresponding day of the week.

Wagner received a patent for the design, and decided to try and convince pharmaceutical companies to use his packaging. But they were reluctant to adopt it.

At the time, drug companies were known for the boring sameness of their prescription packaging. Wagner was told that a special package just for birth control wasn’t needed and seemed commercial and flashy. His design was turned down by every company he approached.

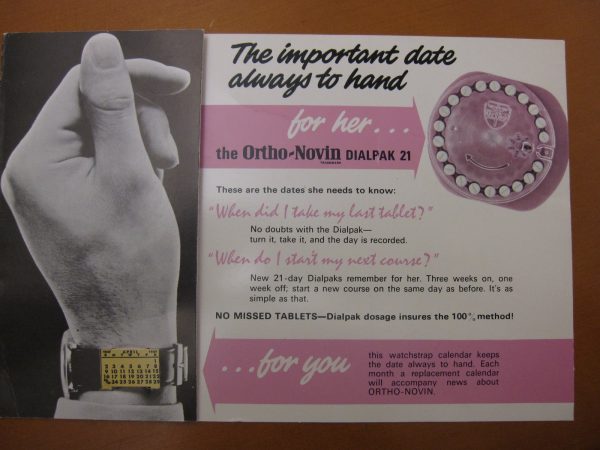

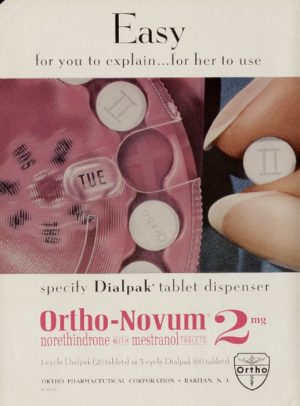

Then, just few months after Wagner had approached a company called Ortho Pharmaceuticals, they released their first birth control pill. And these pills came in a circular plastic container, with a dial that moved each day to reveal the next pill. It was called the Dialpak. It looked very familiar to Wagner. He threatened a lawsuit, and in December 1964, signed an agreement with Ortho Pharmaceuticals — and later with other companies — for royalty payments.

Eventually, David Wagner got tired of chasing royalty obligations from pharmaceutical companies and he sold the patent rights to Ortho Pharmaceuticals. He returned to his quiet life in Illinois. But his design became a national sensation.

As pharmaceutical companies began marketing these new birth control pills they faced a couple of obstacles — obstacles that packaging design would help to overcome.

First of all, the pill marked a major turning point in the pharmaceutical industry. Before birth control, only sick people took pharmaceutical drugs. The birth control pill was one of the first prescriptions intended to be taken by healthy Americans.

And so pharmaceutical companies designed the packaging to look, not like medicine, but instead like an ordinary, everyday object. It was Wagner’s disc with bright colors and graphics.

The other challenge faced by the pharmaceuticals companies was the conservative outlook of the predominantly male corps of doctors. Some were wary about the revolutionary impact the birth control pill would have on sex and gender roles. In 1967, a group of doctors gathered in a symposium called “The Pill and the Puritan Ethic” where they discussed the ethical dilemmas posed by young and unmarried women “demanding and needing” contraceptive advice.

Not only were physicians grappling with issues that were actually none of their business, they were also wondering if women were even capable of following the directions for taking the pill. Pharmaceutical companies responded with ads aimed at physicians, which declared their packaging as “the fool-proof” method.

As the 1960s progressed, more and more women began taking the pill, and its invention was hailed as a major feminist milestone. But there was a darker side to the pill as well. The pill of the 1960s was not the same pill prescribed today.

The old pill had about seven times more estrogen. And this high dose of estrogen caused negative side effects like dizziness and nausea, as well as more serious problems like blood clots and a higher risk of cancer.

Some of these problems had been apparent in early birth control trials. But the trials had been conducted in the 1950s in Puerto Rico, where the pill was primarily tested on low-income women, many of whom were not even aware they were participating in a medical trial. Researchers mostly ignored their complaints.

As the pill moved into the mainstream, most women did not hear about these health risks from their doctors. And it was hard to fathom that the pill that came in pink plastic compacts — the pill that millions of women carried around in their purses — could be dangerous.

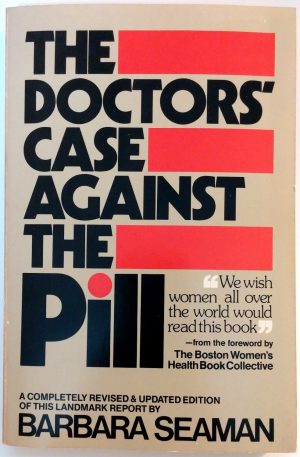

Then in 1969, journalist Barbara Seaman published a book called “The Doctor’s Case Against The Pill,” which exposed the dangers of the birth control pill. Her book inspired Congress to hold hearings to investigate their safety. But no women were invited to testify. It was a panel of men.

Then in 1969, journalist Barbara Seaman published a book called “The Doctor’s Case Against The Pill,” which exposed the dangers of the birth control pill. Her book inspired Congress to hold hearings to investigate their safety. But no women were invited to testify. It was a panel of men.

So women started showing up at the hearings, demanding that their views be heard. A group of women from the activist group DC Women’s Liberation convened at the Capitol with prepared questions and bail money tucked in their socks. The women strategically placed themselves in the middle of audience rows and repeatedly interrupted the hearings demanding more transparency.

These hearings exposed the fact that some doctors had long been aware of the negative side effects of the pill, and many had failed to adequately alert their female patients. The situation left many women feeling torn. They were grateful for the freedom and autonomy the pill gave them, but they also felt betrayed.

The hormonal dosage of the pill was gradually lowered, and it became much safer for women. And one of the longer term legacies of the pill has been to elevate the status of patients from passive receivers to active consumers who could raise questions and concerns.

In turn, this has led to another enduring innovation related to pill packaging: feminist health activists successfully changed FDA policy to require a typed warning of side effects to be included in every birth control package. This laid the groundwork for the side effect warnings that come in all prescription packages today.

So today, when you pick up a prescription — any prescription — that little typed sheet you get that lists every side effect, from the mild to the terrifying — you have birth control to thank for that too.

Meanwhile, other designers have also improved on the packaging itself — in 1999, Martha Davis helped develop a compact reusable exterior case (the “Personal Pak“) to look more discreet and reduce waste, all while carrying forward the circular shape of Wagner’s original design.

Comments (3)

Share

Thank you Wagner.

I’m curious about the number of pills in the package. Many packages now contain 28 pills, instead of the original 20. The last ones don’t contain any active ingredients. How did that come about?

The first 7 pills in packs today are just placebos you take during your meses. It’s to encourage women to continue the habit of taking a pill everyday so they don’t forget. You don’t have to take them, however, and can take just the original 20 which have the actual medication in them.