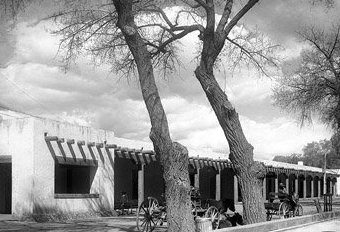

Santa Fe is famous in part for a particular architectural style, an adobe look that’s known as Pueblo Revival. This aesthetic combines elements of indigenous pueblo architecture and New Mexico’s old Spanish missions, resulting in mostly low, brown buildings with smooth edges. Buildings in the city’s historic districts have to follow a number of design guidelines so that they conform with the dominant style. Deviating from those aesthetics can stir up a lot of controversy.

But this adherence to the “Santa Fe Style” hasn’t always been the norm. For a time, there was actually a powerful push to “Americanize” the city’s built environment. Then, over a century ago, a group of preservationists laid out a vision for the look and feel of Santa Fe architecture, and in the process dramatically transformed the town.

Adobe construction has a long history in northern New Mexico with mudbrick buildings dating back hundreds of years. This building material was favored both by the indigenous people of the region and by the Spanish settlers who arrived later on.

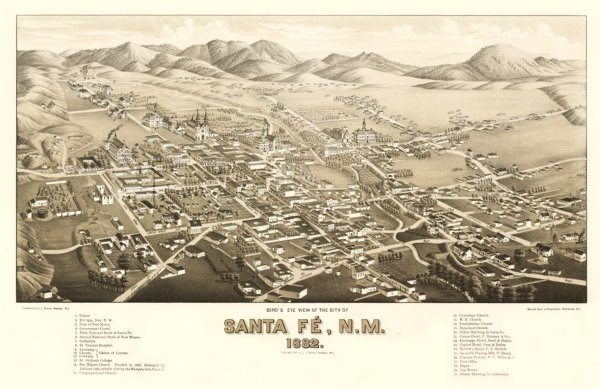

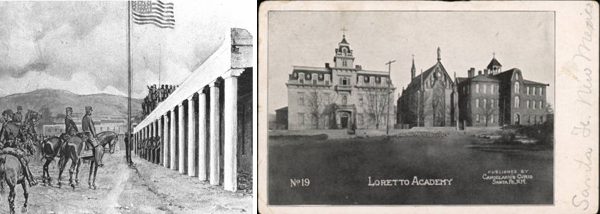

But back in the 1800s, when New Mexico was vying to become a state, Santa Fe actually tried to leave its mud-based architecture behind. There was a push to build new structures in Italianate, Romanesque, Neo-Classical, and other European styles. Local leaders hoped this architectural posturing would help convince Congress to let New Mexico into the Union. At the time, the people in the territory were largely indigenous or Hispanic. Many congressional leaders perceived the region as a dusty foreign outpost unlikely to integrate into mainstream American culture.

Eventually, in 1912, after more than 60 years of trying, New Mexico became a state. But these attempts to fit in cut both ways — they made places like Santa Fe look more like the rest of the U.S., but they didn’t help it stand out. The city began shrinking to the point that the mayor appointed a planning board and charged them with coming up with a strategy to save Santa Fe. The solution, they decided, was tourism.

But they had noticed a trend: many of the people who passed through Santa Fe didn’t stay there. They pushed north toward the pueblos. And so the board created a plan that’s become known as the 1912 Plan. It recommended the city preserve its traditional adobe architecture. But it went even further. It recommended that new development should also be done in the “Santa Fe” style. They wanted to create a kind of citywide architectural brand based on local traditions.

At a time when most historical preservation revolved around individual buildings, Santa Fe decided to broaden its scope dramatically. Most historic preservation at the time was focused on single buildings with connections to Revolutionary or Confederate leaders — places like Monticello or Mount Vernon, for instance. Santa Fe instead decided to focus on the vernacular architecture of the region. The aesthetics of Santa Fe would be carefully crafted and preserved. Rather than pretending to be a conventional American city, the idea was to radically embrace local differences, partly in a bid to attract visitors.

And the plan began to work, attracting tourists as well as anthropologists, artists, and others. Architects caught on quickly, and began building in the desired style — not just homes, but commercial and institutional structures like stores, churches, and courthouses. Designers like John Gaw Meem became leaders of this hybrid style, often using modern materials like steel and concrete to mimic the traditional adobe look. Between 1920 and 1930, Santa Fe went from having 200 hotel rooms to 600 hotel rooms.

Then, in the 1950s, a new style of architecture sweeping the world began to threaten the city’s aesthetic: Modernism.

Tourism was also driving more development and the city was growing. And so preservationists pushed for the city to pass an ordinance in 1957 that further refined Santa Fe’s stylistic rules. The ordinance created a large historic district in the center of the city. Any changes to a building in the district had to be approved by a design board.

The district impacted by these new design rules included some of Santa Fe’s oldest neighborhoods. They were full of Hispanic families, some of them living in adobe houses that had been built by their ancestors.

Through the next couple decades, Santa Fe’s popularity continued to expand. In the 1970s, an oil boom in Texas sent waves of new-minted tycoons to Santa Fe, where they began buying up homes in the city’s historic districts. Then, in the 1980s, international travelers started to visit as well. The city of around 50,000 residents started getting over a million visitors a year. And some of them also started buying up old historic homes, driving gentrification.

In Santa Fe, what started out as a vernacular grown out of traditional techniques and the use of materials on hand had evolved into an aesthetic of the elites, something carefully replicated for show. The popularity of this look also led the city to extend the historic districts and to implement further restrictions. They placed limits on the height of buildings. Commercial districts were encouraged to adopt the adobe look and so Santa Fe began to have fake adobe IHOPs and other franchises. A wave of brown stucco washed over the city.

Of course, for long-time residents of the region, ever-higher costs of living became challenging. The style itself may not have been directly to blame, but impacts on affordable housing (including higher land prices) grew out of its popularity. Traditional solutions like increased density or building taller have met resistance from people who lament changes to the city’s traditional character.

In some ways, Santa Fe became a victim of its own success. Early preservationists set out a vision for protecting Santa Fe’s historic look and successfully fostered a tourism industry that is still the foundation of the city’s economy. But the popularity of Santa Fe also helped to widen serious inequalities. Many people working in industries supported by local tourism have been priced out of town. Meanwhile, many expensive homes in town go largely unused, sitting as seasonal residences for cosmopolitan travelers.

Some people have started to take a more holistic view of preservation in light of these side effects, looking at not only maintaining the aesthetics of Santa Fe, but also the community itself. In recent months, the city’s Historic Preservation Division has been working on a study to quantify the changes that have happened in the city’s historic districts over the past few decades. They’ve found that between 1980 and 2018, even as the population of Santa Fe grew, its historic districts emptied out. Many longtime residents left their homes or converted them into rentals. Those people who remain are generally whiter, wealthier, and older.

On the flip side, some argue that any efforts to roll back this tide would be too little, too late — much of the Hispanic population has already left the historic neighborhoods and gentrification has already taken its toll. So, for some preservationists, the only thing that can still be saved is the historic built environment of Santa Fe.

Some affordable housing advocates say there are other historic models that could offer a guide, if the city wants to root its building practices in history. Traditional pueblo architecture, for example, is more dense than Santa Fe’s neighborhoods tend to be.

Early preservationists tried to freeze the city in a moment in time, and on some level, they succeeded. But in holding so tight to the aesthetics of one period, the city actually lost a lot of the people and cultures that used to make Santa Fe what it was.

Comments (1)

Share

This completely sums development on Prince Edward Island Canada and local residents anti new higher density development. Need for housing people who work seasonal and can’t afford to live near where they work.