461 Dean Street, Brooklyn’s new modular skyscraper, has been making headlines, both for being the world’s tallest modular building and for being overdue and over budget. What’s notable about 461 Dean, is that it approached modular housing from a luxury angle, rather than the usual sci-fi solution to overcrowding and other social crises.

Still, this skyscraper failed to realize the goals of modular design: simplicity, economy, swiftness of construction, repeatability, and flexibility. Moreover, 461 Dean is not alone. In fact, it is merely the latest in a long, vibrant history of mass-modular housing pitfalls.

Modular vs. Prefab

Modular construction and prefabricated construction are different but often overlap — there are usually prefabricated parts of the modular scheme, for instance.

Prefabricated construction consists of any structure designed and produced in a factory prior to building.

Modular construction consists of some sort of frame or structure in which smaller units (called modules, which are often fabricated off-site) are assembled onto the frame on-site. Modules range in size and complexity from entire apartments (e.g. 461 Dean Street) to individual rooms. The term module in this context does not refer to individual elements such as single walls, doors or windows, but rather self-enclosed dwelling spaces.

While prefabricated housing has had a long and prosperous history, modular architecture is a much more recent phenomenon. By the time modular construction and planning began, prefabrication had already been around for centuries.

Origins of Modularity

The first modular housing schemes can be traced back to Buckminster Fuller, whose flexible housing experiment of the 1920s and 30s, the Dymaxion House, came with things like notably advanced prefabricated bathroom modules.

These modules were shipped to the US military for use during World War II. However, the full extent of Fuller’s modular ideas was never completely realized due to a lack of funding in his Dymaxion company, and the engineer-architect soon moved on to other projects.

The first successful construction of a fully modular home system did not materialize until 1933, with the Winslow Ames House by Robert W. McLaughlin and his company, American House, Inc.

This innovative house was built with the help of a new exterior finishing material called Cemesto, a panel board made partly of sugarcane, patented by the John B. Pierce Foundation. The Winslow Ames House consisted of several room modules serviced by a ‘service core’ to which all bathroom, kitchen, plumbing, and heating systems were attached.

In 1942, the US Government used a similar Cemesto prefabrication system to build the top secret town of Oak Ridge, Tennessee, home of the Manhattan Project, virtually overnight.

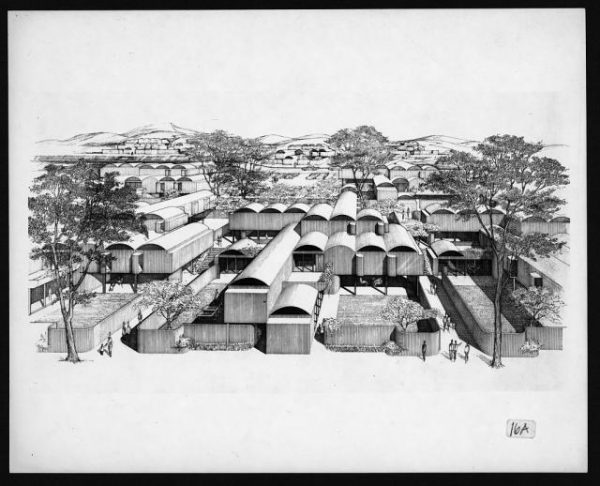

They hired the firm Skidmore, Owings, & Merrill, to come up with a scheme called “Flexible Space” – fully modular homes flexible enough for the variety of families soon to inhabit this clandestine new place. The houses came in discrete sections, cast in cemento, and assembled on site in slightly varying configurations.

Modularity for the Masses

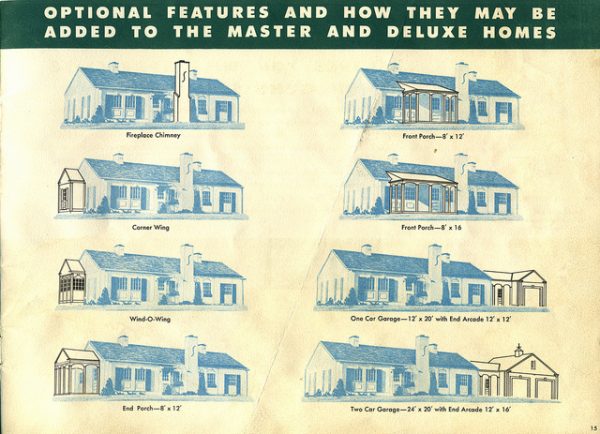

After the war, the concept of modularity spread to the burgeoning suburbia, albeit in a mellowed-out way, in the form of plug-and-play panel systems of the 1940s and 50s Lustron and Gunnison prefabricated houses.

These popular houses consisted of steel frames with customizable features like a varying selection of kitchen and bath systems, windows and doors, and add-ons like porches, porticos, and garages. While only somewhat modular in design, the houses helped introduce the concepts of modularity to the general public.

The modular idea captivated many throughout the 1950s, notably the architect and designer George Nelson, most famous for his mid-century modern furniture. Nelson led the transition to new emerging concepts of modularity, expressing modular construction on the exterior (unlike his predecessors, who sought to obscure the modular nature of their designs). His ongoing Experimental House concept combined new materials such as affordable plastics, with the space-age futurism Nelson was most famous for.

In the 1960s, the futuristic aesthetic language pioneered by Nelson and the Eameses and popularized by television programs like Star Trek and current events, including the Space Race and the Atomic Age, became infused in the modular housing schemes of the 1960s. These schemes, which focused on installing individual housing units on a mass structural frame, were forward-thinking solutions to the proposed upcoming overpopulation crisis.

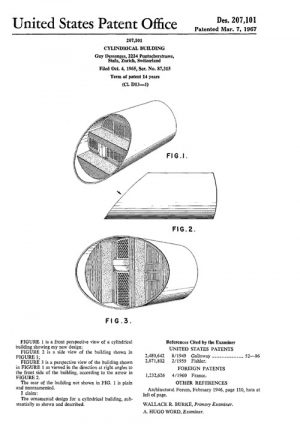

The modular era of the early 60s opened with fanciful leisure housing by the French architect Guy Dessauges, whose elegant capsule houses on pylons offered panoramic views of their scenic locations.

The concept of modularity reached an unattainable level of complexity in the 1964 with Plug In City, a mega-scale modular concept by the British experimental architecture collective Archigram. Though it was never built, Plug-In-City set the stage for the idea of the interchangeable city for the somewhat-dystopian future predicted in the Cold War atmosphere of the 1960s.

Perhaps the biggest accomplishment of this heydey of modular experimentation was the prefabricated modular megastructure by Moshe Safdie, Habitat 67, built for the 1967 Expo in Montreal.

Habitat 67, a graduate project by Moshe Safdie, who studied at McGill University, consists of up to 12 stories comprised of 354 identical prefab concrete apartments arranged in a variety of combinations. The project focused on the integration of light, fresh air, and open space, in the context of a dense, urban community prototype. The apartments still stand, and still sell for upwards of hundreds of thousands of dollars (a rarity for experimental housing schemes).

On the other side of the world, Japan, confronted by a post-war population and manufacturing boom, developed the architectural style of Metabolism, which focused on flexibility, modularity, and the Archigram-like concept of interchangeable units.

Though the Metabolist group was only active until the 1973 Energy Crisis, they had a large effect on American architects and thinkers, who visited for the 1970 Expo.

Like Archigram, the Metabolists concepts were mostly hypothetical, never reaching past the model stage. However, they did manage to have a few buildings built. The most notorious and interesting of these structures was the 1972 Nagakin Capsule Tower, by Kisha Kurokawa.

The Nagakin Capsule tower consists of 140 self-contained prefabricated capsules, complete with bathrooms, cabinetry, and a built-in HiFi set. The tiny capsules, designed to be removable and replaceable, only measure 7.5 x 6.9 x 12 feet — a predecessor to today’s increasingly popular micro-apartments.

Despite its striking appearance, the tower has been in danger of demolition for over 10 years; for now, preservation efforts have forestalled the potential loss of such an important building.

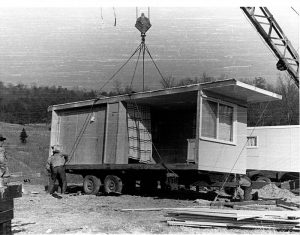

The American architect, Paul Rudolph, most famous for his Brutalist government buildings, was inspired by modular projects seen in World Expositions and those by his European contemporaries. Rudolph devised a mass-housing project in New Haven, Connecticut, near Yale where Rudolph taught architecture. Rudolph’s concept took existing housing infrastructure developments, namely the single-wide trailer, and applied it in a Habitat 67-esque fashion.

Rudolph’s project, Oriental Masonic Gardens, was assembled from 148 prefabricated units, grouped in clusters of four around a central utility ‘core’. The living spaces were based on stacked units – the ground floor unit consisted of living spaces, with bedrooms located within the second story unit. A third story unit could be added for additional living spaces. The project was ultimately unsuccessful. According to Rudolph in a later interview: “People hated it. First of all it leaked, which is a very good reason to hate something, but I think it was much more complicated than that. Psychologically, the good folk who inhabited these dwellings thought that they were beneath them. In other words, the deviation of the dwelling was not something to their liking.”

Unsuccessful developments such as Rudolph’s pushed public taste away from the mass modular concept as the 70s came to a close. The resolution of the 1970s energy crises combined with the new era of Neoliberal economic theory and prosperity created by the technological advantages of the Green Revolution, created a boom in consumerism manifested as house-building during the Reagan era. Americans were all too happy to put the grim weight of social programs and societal turmoil (including failed social housing) of the past two decades behind them and usher in a period of increased private spending and private ownership.

While modular apartment concepts retained favorability in the densely populated cities of Europe during this period, the modular housing concepts of the 1980s in America returned to the thinking of the 1940s and 50s, focusing on the individual home rather than the collective housing prototype. The 1980s saw modular housing technology applied to the construction of suburban homes, with companies such as Unity Homes devised modular methods of building as an alternative to the often-stigmatized manufactured homes of the time.

These new modular houses were constructed from parts in a factory, where a steel frame was used as the chassis on which the house was transported to the construction site. Here, the home was picked up with a crane and assembled on a prepared foundation. The frame then went back to the factory for construction of the next “off frame” modular. These modular methods, whose origins are directly linked to the early cemento houses of Oak Ridge, Tennessee, remain popular in home construction today.

Contemporary Modularity

The great advances in technology during the 1990s and 2000s inspired a new generation of architects to return to the concept of experimental modular housing. Improvements in computer rendering led to innovative manufacturing concepts like the Klip House, whose computer-designed parts could be snapped together like LEGOs.

The flexible nature of Klip House aimed to appeal to those seeking a single family detached home that could adapt to their changing needs. With this system, the need for more space could be solved by simply clipping in another module rather than moving out or building an entirely new home (therefore mitigating the relentless urban sprawl of the last four decades).

The most recent developments in modular housing have sought to solve an entirely new problem: urban housing affordability. As more and more wealth moves into cities, and speculation on urban property rises, displacement and gentrification have created an urban housing affordability crisis spanning cities from coast to coast.

An unexpected side effect of this problem is the displacement of young people and creative-types, who have become a new sect of marginalized home-buyers, priced out of the places where their careers can thrive. New types of housing have arisen for those desperately looking for low rents: container houses and modular micro-apartments.

Container housing, a creative reuse approach in which excess or discarded shipping containers are transformed into small homes, hit the mainstream consciousness in 2000, when the firm Urban Space Management completed the Container City I project in the Trinity Buoy Wharf area of London. The project bears many similarities to Rudolph’s Oriental Masonic Gardens, in that several discrete units are assembled into a complex of private homes. The firm has gone on to complete 16 additional projects.

Though popular in Europe, complicated zoning laws in the US have prevented the proliferation of shipping container developments, despite claims that they could be an effective affordable housing solution.

The micro-apartment, a housing solution with origins in extremely high density cities such as Hong Kong, has spread to cities in the US, with a notable projects in New York and Seattle. Projects such as My Micro New York, consist of prefabricated 313 square-foot modules assembled on a steel frame on-site.

The micro-apartment, with its origins in projects like Nagakin Capsule Tower, aims to provide safe living spaces with lower rents – a response to situations where bedrooms are divided ad hoc into separate dwelling spaces under the nose of the law in order to allow more inhabitants to save money on rent. Time will tell whether or not these schemes are ultimately successful, as is the case with the vast majority of mass-modular housing concepts.

Though mass modular housing has had a few successes such as Habitat 67, the majority of projects either never make it past the planning stage or are resounding failures. Yet the plug-in-play flexibility of modular construction has always inspired forward-thinking architects. The harsh reality of our times is that the fossil-fuel centric world of sprawl is short-lived and unsustainable. With the proliferation of new forms of housing and non-nuclear living situations, combined with our highly technological age, the conditions are ripe for a golden age of affordable modular housing — as long as zoning boards, cities, and individuals keep an open mind.

Leave a Comment

Share