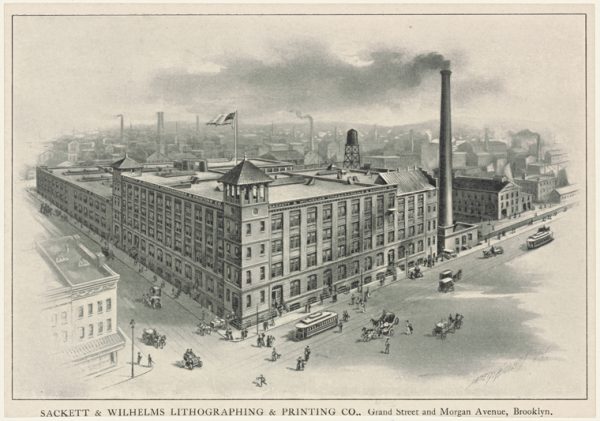

In the summer of 1902, the Sackett and Wilhelms Lithography & Printing Company in Brooklyn, New York had a problem. They were trying to print an issue of the popular humor magazine Judge, but the humidity was preventing the inks from setting properly on the pages.

The moisture in the air was warping the paper and messing up the alignment. So the company hired a young engineer named Willis Carrier to solve the problem.

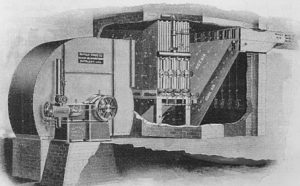

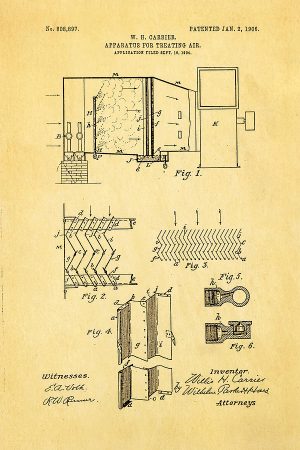

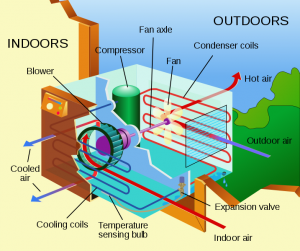

Carrier developed a system that pumps air over metal coils cooled with ammonia to pull moisture from the air, but it had a side effect — it also made the air cooler. The room with the machine became the popular lunch spot for employees. Carrier had invented air conditioning, and began to think about how it could be used for human comfort.

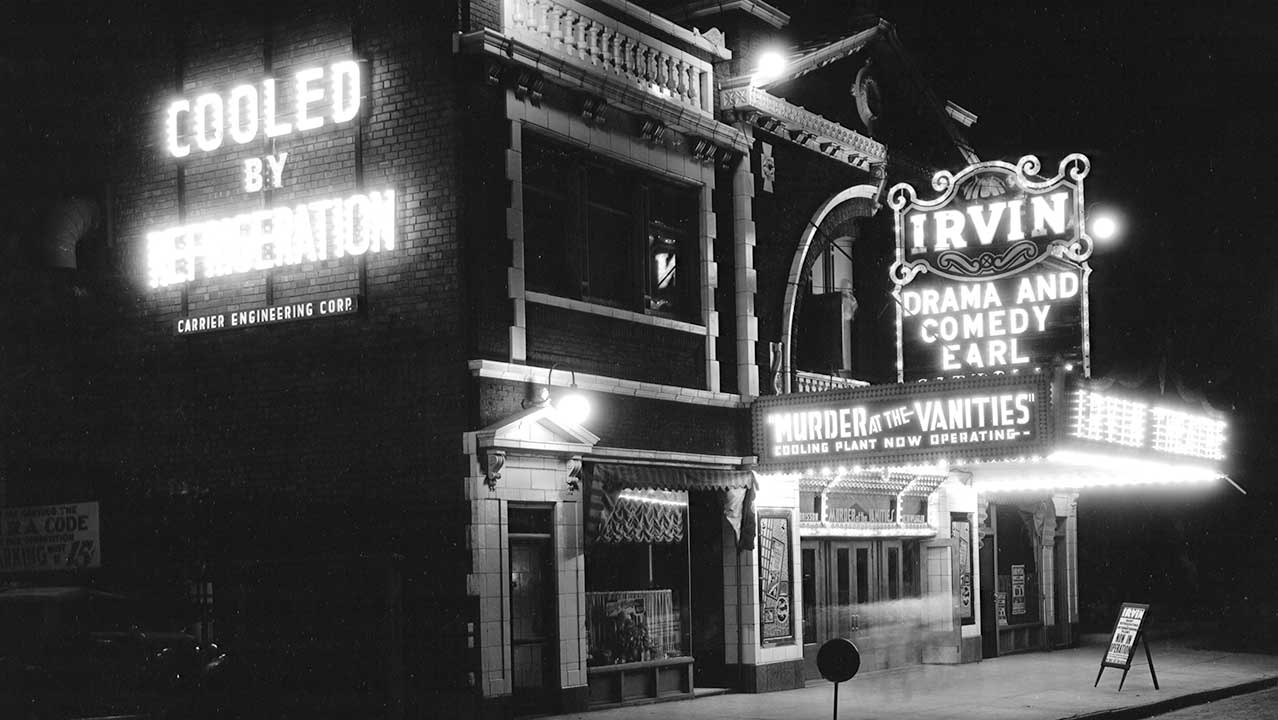

Before air conditioning took off, a hot and crowded theater was the last place anyone wanted to be during the summer. So Carrier approached a bunch of theater owners and pitched them on his technology — it wouldn’t be cheap, he explained, but higher ticket sales could pay for it.

Soon, theaters were advertising chilled air and drawing huge crowds, eventually helping to spawn the “summer blockbuster” phenomenon.

But air conditioning would do a lot more than cool entertainment spaces. Ultimately, it would dramatically change where people in the United States lived and the design of other buildings, including homes.

Luxury AC Goes Mainstream

But the air conditioning revolution didn’t happen all at once. Before World War II, a few wealthy elites had systems installed in their mansions, but mechanically chilled air was still seen as a luxury.

Willis Carrier wanted to change that. In a 1929 speech, he said: “air conditioning and cooling for summer may become a necessity rather than a luxury, and we will look upon present times as marking the end of that ‘dark age’ in which there was but relatively little cooling for human comfort.” And he was right.

Early AC systems were massive, but by the late 1940s, Carrier and other companies were selling air conditioners that could fit in your window. But they were expensive, and it wasn’t clear at first that people would buy them. Companies helped sell air conditioning through advertisements that targeted women and emphasized the ability to completely control the indoor climate.

In 1960, 13% of homes in the United States had AC — by 1980, it was up to 55%. Today it’s close to 90%. In just a few decades air conditioning went from luxury to necessity, just as Willis Carrier predicted. And the ubiquity of AC has had a serious impact on how and maybe most profoundly where we live. Hot places like Arizona and Florida saw huge influxes of residents. A mass migration to the so-called “Sunbelt” changed the political map, too, as electoral college seats moved with citizens. And since a lot of these new southward migrants were conservative retirees, they voted Republican, forming a key target demographic in Reagan’s election in 1980.

Vernacular vs. Conditioned Spaces

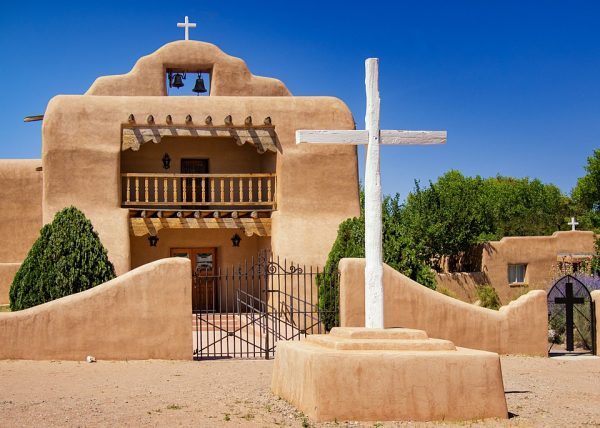

Of course, people did live in these states before the advent of air conditioning. And they developed strategies to beat the heat, including forms of vernacular architecture that responded to the local environment.

In the desert southwest, for instance, houses were traditionally built with hefty materials like adobe and stone that can absorb heat. This “thermal mass” soaks up solar heat by day and releases it at night.

In humid southeast, a lot of vernacular architecture was designed to maximize shade and air movement. There were screened-in sleeping porches, breezeways between rooms, and cupolas in the roof to draw cool air up through the house.

On-demand cold air freed architects from the challenge of designing a home that was uniquely suited to the climate around it. Air conditioning systems were expensive, but home builders made up for the costs in part by cutting down on passive cooling features, and little by little the local architectural traditions rooted in the climate gave way to tightly sealed, mass produced tract homes for growing suburbs.

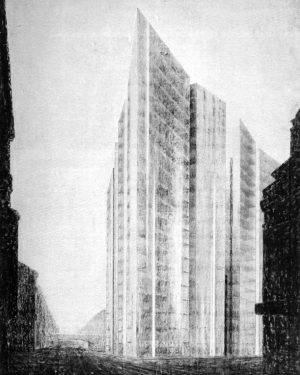

Air conditioning also revolutionized the design of other building types, including skyscrapers, schools, and offices. Before AC, the only source of cool air was the outdoors, and so offices usually had high ceilings and lots of windows that people could open. The floor plans of many mid-rise buildings from the early 20th century often had thin irregular shapes designed to give more access to light and air. But with air conditioning, buildings could fill up the entire lot with offices deep inside the core of the building and nowhere near a window.

This evolving technology also changed facade design — shading systems were no longer as essential and buildings could have uninterrupted, glass-and-steel facades with windows that didn’t open. For a lot of architects, this was seen as a plus — they could stop worrying about designing for human comfort and focus on sleek, Modernist aesthetics.

Still, as a consequence of all of this, the modern built environment in the United States is now totally dependent on air conditioning. A lot of our buildings would be uninhabitable in the summer without AC, and all of the electricity needed to keep it running.

According to Stan Cox, author of the book Losing Our Cool, the United States now uses as much electricity for air conditioning as it did for all purposes in 1955. And as homes have increased in size the more space needs to be cooled. “It’s crazy to think about,” says Cox, “that on a hot day here in Kansas there are [huge] houses being kept at 70 degrees all day long and all the occupants are off [at] work and school. And so it’s not cooling a human being at all.”

And that excessive AC use is a real problem, because air conditioning might be keeping our buildings cool, but it’s making the outside world hotter. Per Cox: “The additional greenhouse emissions from air conditioning in the United States add up to about 500 million tons of CO2 equivalent per year,” more than the entire construction industry.

And this building approach is being exported to other countries in places like the Middle East and Asia, further upping power demands.

Modern Meets Traditional Architecture

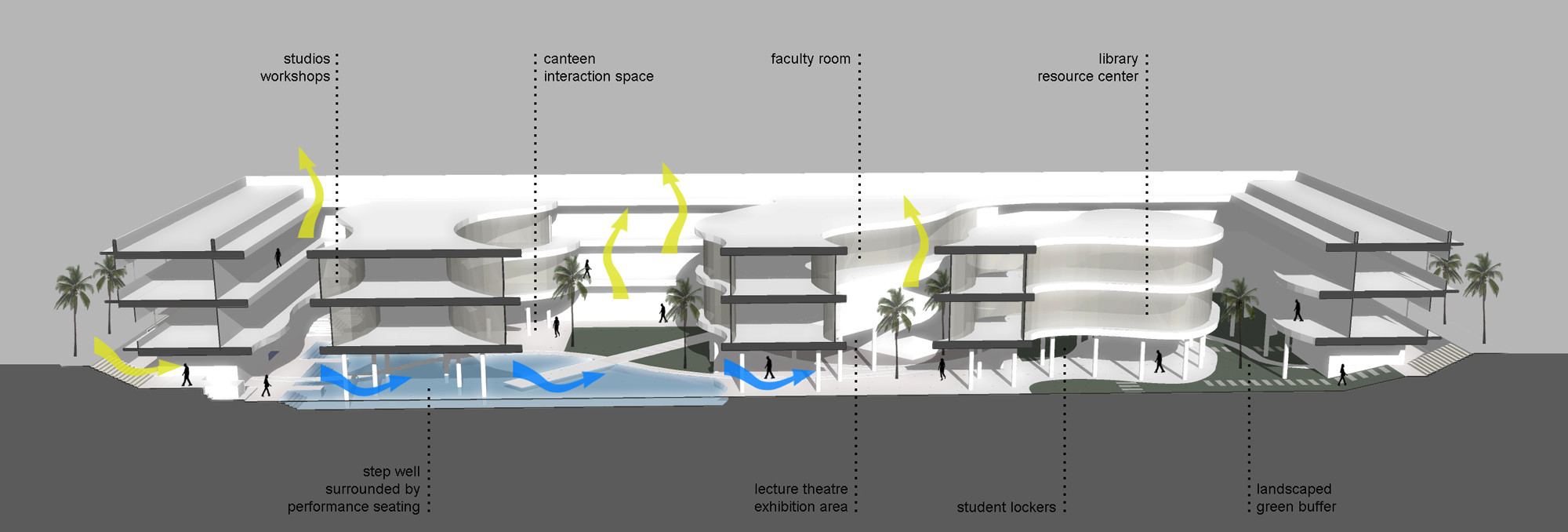

Manit Rastogi, an Indian architect and co-founder of the New Delhi firm Morphogenesis, sees a lot of new glass-and-steel buildings that look like any others of their kind around the world. But he is also familiar with regional vernacular traditions designed to keep people cool. His firm looks to these examples to design new buildings, blending Modern aesthetics with passive cooling techniques.

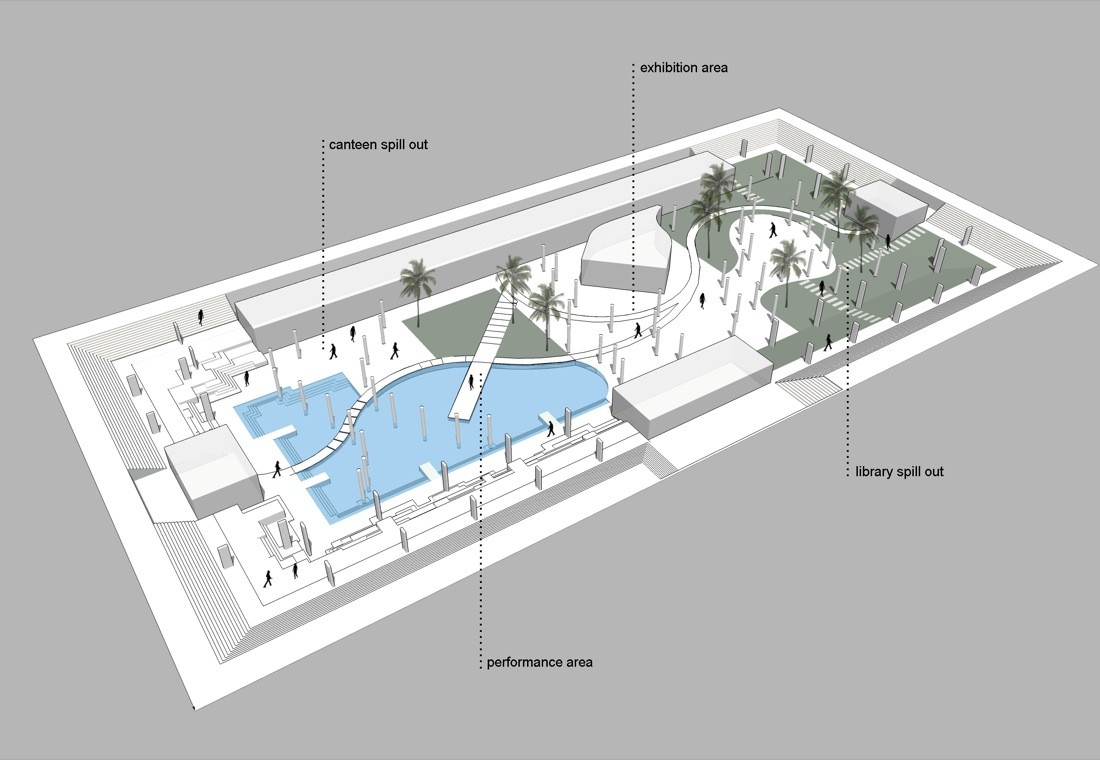

“So the Pearl Academy of Fashion,” he says, in reference to one of his projects, “is on the outskirts of Jaipur which is essentially a desert climate.” In his work on the school, he studied old palaces and forts for inspiration on cooling techniques. And he was particularly impressed by a feature called a “baoli,” or: stepwell. These are basically pools of water dug deep into the ground beneath the building and surrounded on all sides by descending steps, intricately carved from stone. The cool temperatures from underground combine with the evaporative cooling of the water to lower the temperature in the palace.

Rastogi decided to put a modern take on this ancient architectural feature in his building. “So we created a baoli,” he says, “across the entire site. We dug three meters down into the ground and we recycle all the water into that stepwell then allowed for evaporative cooling to come up and cool the site down.”

Meanwhile, the top of the building is insulated using earthenware pots. And on the sides they put “jalis,” traditional latticed screens which keep sun out but let light in.

All of the these passive cooling strategies combine to lower the temperature within the building. When it’s 115 degrees Fahrenheit outside, it’s around 84 degrees inside the Pearl Academy. That may sound hot, but for the region, it’s pretty pleasant. Rastogi says thermal comfort is relative.

Thermal Monotony

These days, architects and engineers around the world generally use thermal comfort standards set by the the American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers. These have historically dictated a rather narrow range for ideal temperatures, which in turn requires more heating and cooling.

And some architects, like Lisa Heschong, see this as problematic — “you will never achieve a static environment where 100 percent of the people are happy,” she says. “There is a huge amount of individual variation in what people experience and what they prefer,” based on factors like age, sex and the kind of climate we are used to. All of this runs against the idea of targeting a single static indoor temperature.

Gail Brager, professor at the UC Berkeley College of Environmental Design, has developed new thermal comfort standards, which have been adopted by ASHRAE, that allow for a wider range of temperatures within buildings. Brager doesn’t want to get rid of air conditioning altogether, but she thinks that we can be more intentional about when and where we use it: “Our environmental conditioning systems think about heating and cooling spaces rather than heating and cooling people,” she contends.

Brager says we could save enormous amounts of energy by letting the temperatures in buildings fluctuate over a wider range, and giving people more tools to heat and cool themselves. To accomplish this, Brager advocates a take a combination of high and low tech approaches. A window that you can open right by your desk is a great personal cooling device. A sweater is a pretty good personal heating device. But Brager and her team are also developing low energy desk fans, foot-warmers, and chairs that can heat or cool.

Thermal Delight

Reducing our reliance on air conditioning is often framed as a loss, giving up comfort, but neither Gail Brager nor Lisa Heschong see it that way. Back in the 1970s, Heschong wrote a beautiful little book called Thermal Delight in Architecture. In it, she argues that we should think about our perception of temperature as a sense. Just like any other sense, temperature can cause us discomfort but it can also give us a lot of pleasure — the feeling of a warm fire in the winter or a cool breeze on a hot summer night. But these experiences require change — they don’t happen in a thermally neutral environment.

Reducing our reliance on air conditioning is often framed as a loss, giving up comfort, but neither Gail Brager nor Lisa Heschong see it that way. Back in the 1970s, Heschong wrote a beautiful little book called Thermal Delight in Architecture. In it, she argues that we should think about our perception of temperature as a sense. Just like any other sense, temperature can cause us discomfort but it can also give us a lot of pleasure — the feeling of a warm fire in the winter or a cool breeze on a hot summer night. But these experiences require change — they don’t happen in a thermally neutral environment.

Gail Brager has done studies on thermal comfort in buildings around the world, and she’s found that people actually prefer naturally ventilated buildings where they can open windows and feel a little control over their own temperatures. And this is a big deal in today’s world where the average person spends 90% of their time indoors.

Comments (18)

Share

As a marketer at an MEP engineering design firm that uses passive design in our work, I was surprised you guys didn’t mention Passive House/PassivHaus design movement (although you pretty much alluded to it throughout the episode).

I loved this piece, regardless, and I’m so pleased to see the wider world getting exposed to passive design as another strategy to address climate change! Thank you!

You’d be surprised at how fast you acclimate to an 80 degree office temperature . I live in Oakland, CA and have spent some time in Jaipur. Many, many places that have AC in parts of India keep it set to around 80F. I only noticed AC going down into the low 70s at very western hotels. When I was there it was 110-115 during the day. Within three days I was totally comfortable with the 80 degree interior and came to prefer it.

It’s a big enough difference from the outside that it’s a huge relief to come inside, but you don’t get chilled like you do with hardcore AC in the U.S. It drives me bananas that I have to carry a sweater in summer because of AC.

Eighty degrees can be quite comfortable, until the humidity gets up to 80 or 90%. In many places, the primary purpose of air conditioning is to remove humidity, not cool the air.

if this episode interested you, you should really check out this article on Kieran Timberlake’s attempt to go A/C free in their office. You’ll have to read it to find out if the experiment worked, but it’s pretty entertaining.

http://www.architectmagazine.com/design/kierantimberlakes-cool-experiment_o

I’m an American from the Southwest living in Germany. I used to hate how cold it would get inside buildings in the summer! and I found the reporting on AC very interesting.

Coming to Germany, in the summer, I found that there’s very little air conditioning, windows are simply opened for cooling. I asked where the air conditioning was, they said they don’t need to waste that kind of energy (something similar was said about drying clothes in a machine).

In the winter, there’s a radiator system, you see them in all buildings, directly under windows. My question for 99PI is, how efficient is this system? Rooms can become quite stuffy and hot, and the window is opened, but I wonder, isn’t all that energy lost?

It doesn’t seem very efficient to me, but I’d love to be proven wrong.

The average price of electricity in Germany is 29.69 euro cents. In the US, it’s 12 cents. That probably accounts for the difference in usage for AC.

I learned you should open the windows every day, even if it’s cold, because if there’s not enough ventilation the air becomes moist and moist air warms up less easily. Also, even with my single-layer windows it is best to have the radiator right below because a small ‘heat wall’ is created. However, having the window open while the radiator is full on always seems like a waste to me. I think it’s about finding the right balance.

I also learned warning up a building costs way less energy than cooling it!

What is the name of the magic chair that was mentioned in the story?

Where can I get that chair?

It’s unfortunately not available commercially yet – we are looking for a manufacturer!

The Hungarian Parliament building had a unique cooling system when it was built in 1880. Initially, two fountains in the square in front of the building were used to evaporatively cool air that could then be pumped through grilles into rooms in the parliament building. (There are grilles in front of each of the seats where members of parliament sit.) After the fountains were demolished in the 1930s, cooling was then achieved by filling two large shafts with tonnes of ice and pumping the cold air around them through the grilles. Remarkably this system was still in use until 1994, and is still in working condition.

Details about the warm/cool chair please.

Ditto – interested in learning where to get the chair.

Still not being produced (yet) for retail as far as I know – sorry!

Wonder if this is it?

https://www.amazon.com/Gentherm-Heated-Cooled-Executive-HC-321/dp/B01HOMYOKS

Honestly I really want that chair mentioned. All other chairs I find that are similar are not that great, some are badly designed, and quite a few seem to be inconsistent in build quality. The Aquon seems pretty good if you just want cooling but it is a basic looking chair so I dont know how it is for posture. And the fan seems a little noisy so I’d probably buy a silent fan to replace it. Anyway please respond if you find a manufacturer as you mentioned in another comment.

Harmonizing Space is about understanding the effect our built environment has on us both physically and emotionally. Space layout, the position of a building in an exceeding location, and also the inner arrangement of individual rooms within the building, will greatly influence the space result.

Building health refers to associate degree rising space of interest that supports the physical, psychological, and social health and well-being of individuals in buildings and also the designed atmosphere. Buildings will be key promoters of health and well-being since most of the people pay the majority of their time near and inside.

this reminded me of “The Story of Mrs. Jones and Her Vacuum Cleaner” which is an excerpt from “Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH” in which Mrs. Jones purchases a vacuum cleaner, becomes the talk of the town, all the women buy them, the power plant makes more soot than ever to power the vacuum cleaners, and the women work twice as hard as before using their new vacuum cleaners.