In the middle of the 20th century, the small town of Jasper, Indiana did something that no other city had done before: they made garbage illegal. The city would still collect some things, like soup cans and plastics, but yucky junk, like food waste, wouldn’t get picked up.

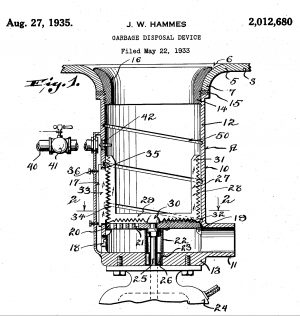

This change was made possible by a new appliance: the garbage disposer – that little grinding machine at the bottom of a lot of kitchen sinks. Most people call it the “disposal” (or “InSinkErator,” or even the “garburator”). In other countries, these machines are less common, but an estimated half of American homes have one.

This change was made possible by a new appliance: the garbage disposer – that little grinding machine at the bottom of a lot of kitchen sinks. Most people call it the “disposal” (or “InSinkErator,” or even the “garburator”). In other countries, these machines are less common, but an estimated half of American homes have one.

Up until the late 1800s, food scraps would often be saved for another meal or repurposed to make candles or soap. However, with the commercialization of food came more waste. In U.S. cities the garbage literally piled up on the streets. This created not only a smelly problem, but a public health one.

Some municipalities started collection services to haul their waste to a dump. Others demanded citizens split up their kitchen refuse from their other waste. The discarded food would get sent to local farmers who used it as feed for their hogs.

By the early 1920s, these haphazard systems of garbage collection were struggling to keep up with 20th century consumerism. Cities and towns were burning garbage, even throwing it into their local river. All of this was seen as spreading disease – it was simply unsanitary.

To deal with the growing garbage problem, a few communities started grinding up their garbage in these massive machines and washing it down into their local sewers. General Electric took this totally new concept – mixing sewage with food waste – and tried to expand on it. They figured: if you could use a large scale grinder to get rid of the town’s garbage, you could maybe build small household ones to eliminate garbage at the source.

To deal with the growing garbage problem, a few communities started grinding up their garbage in these massive machines and washing it down into their local sewers. General Electric took this totally new concept – mixing sewage with food waste – and tried to expand on it. They figured: if you could use a large scale grinder to get rid of the town’s garbage, you could maybe build small household ones to eliminate garbage at the source.

By the late 1930s, people started getting very excited about garbage disposers. Scientific American predicted that the disposer would make the garbage can obsolete. An article in House and Garden magazine introduced readers to new garbage tech, like rubber plate scrapers and waxed garbage pail liners — but its highest praise was for the disposer.

By the late 1930s, people started getting very excited about garbage disposers. Scientific American predicted that the disposer would make the garbage can obsolete. An article in House and Garden magazine introduced readers to new garbage tech, like rubber plate scrapers and waxed garbage pail liners — but its highest praise was for the disposer.

For his part, the mayor of Jasper, Indiana saw an ad for these new-fangled machines, bought one, tried it out, and developed what became known as The Jasper Plan. The idea was simple, if expensive: every home in the town would be outfitted with a garbage disposer.

Not everyone thought widespread use of these machines was a good idea. There was a fear that the disposer would clog pipes and lead to expensive repairs. And so some places, including New York City, actually moved to ban garbage disposers.

But the city council in Jasper, Indiana was confident their disposer plan would work because they were already planning to build a new wastewater treatment plant. They could just amend those plans and upgrade Jasper’s sewers to accommodate for all this new incoming garbage.

But the city council in Jasper, Indiana was confident their disposer plan would work because they were already planning to build a new wastewater treatment plant. They could just amend those plans and upgrade Jasper’s sewers to accommodate for all this new incoming garbage.

To enforce the adoption of disposers, the town simply stopped collecting organic waste. Residents were thus pushed to buy the machines, albeit at a steep discount. Other towns and cities in the midwest saw the plan unfold and began to follow suit.

In Jasper and around the country, the garbage disposer worked its way into postwar housing under the guise of public health and the elimination of garbage. The appliance never did deliver on those promises, but garbage disposers remain a staple of many American kitchens for one simple reason – they’re convenient.

Today, treated wastewater organics create a byproduct known as sludge. In most places, sludge is simply shuffled to a landfill, but in Jasper, they use it as fertilizer. Local farmers often get it for free or a pittance. However, not everyone is on board with this approach. Some researchers say applying sludge back onto farmland can inadvertently pollutants into groundwater.

Today, treated wastewater organics create a byproduct known as sludge. In most places, sludge is simply shuffled to a landfill, but in Jasper, they use it as fertilizer. Local farmers often get it for free or a pittance. However, not everyone is on board with this approach. Some researchers say applying sludge back onto farmland can inadvertently pollutants into groundwater.

Regardless, all of this sort of obfuscates a larger point. We spend a lot of time thinking about how to build machines or find new ways of dealing with the remains of what we buy. But there’s a more effective way to keep garbage off the streets, out of the sewers, and out of the landfill. It’s figuring out ways to avoid creating food waste in the first place. Still, that would require all of us to take a second and think about what’s gonna happen to our garbage next. Which isn’t as easy as flipping a switch and watching it all disappear down the drain.

Leave a Comment

Share