When Herbie Miller was growing up in East Kingston, Jamaica in the 1950s and 60s, he and his friends would put on their best outfits and head into the city. From blocks away, they could hear music pumping out through giant, powerful speakers set up at dance halls, bars and social clubs all over downtown. The sound was irresistible. And so Herbie and his crew would just follow their ears. Along the way, they’d run into other kids like them — everyone looking for the exact same thing: the perfect dance party.

The guys would collect scrap metal and recycle empty bottles just to earn enough cash to pay the door. But sometimes, they’d still come up short. These parties were the hottest dance scene on the island – with DJs spinning the latest tracks by artists like Alton Ellis, Don Drummond, and Roland Alphonso. If they got lucky, a sympathetic bouncer would suddenly open the gate and wave Herbie and his buddies through. When Herbie was growing up, these amazing parties — sometimes called lawn dances, or blues dances — were happening on the regular all over downtown Kingston. And one of the things that made them burn so damn hot, was the technology that powered the party.

Oh Carolina by The Folkes Brothers is an early example of the shift Jamaican music was making from strict R&B influences to more indigenous sounds like Nyabinghi drumming.

Jamaica is famous around the world for its music, including genres like ska, dub, and reggae. It’s tempting to think that those powerful amplifiers and giant speakers were designed to perfectly capture Jamaica’s indigenous sounds. But it’s actually the other way around. Those speakers and amps came first. And the electricians, mechanics and engineers who built and adapted that technology would then play a decisive role in the creation of Jamaica’s modern music. They helped pioneer approaches to making and performing music that would spawn whole other scenes from the Bronx to the UK.

These dance parties first emerged in Jamaica in the decade following WWII. That’s when the deeply underdeveloped British colony started to grow economically. One big boost came from US tourism. The demand for musical artists in the resort towns was so high, it sparked an exodus of musicians out of the capital city of Kingston. Many of them packed up their saxophones and guitars, and struck out for tourist hot spots in search of higher paying gigs. So a handful of small businessmen, inventors, and audio engineers across central and West Kingston began to improvise a way to give the people the dance parties they craved without any live musicians. As small as they were, these parties would soon inspire some big advances in technology. And that tech was gonna help West Kingston’s nascent dance scene explode.

These dance parties first emerged in Jamaica in the decade following WWII. That’s when the deeply underdeveloped British colony started to grow economically. One big boost came from US tourism. The demand for musical artists in the resort towns was so high, it sparked an exodus of musicians out of the capital city of Kingston. Many of them packed up their saxophones and guitars, and struck out for tourist hot spots in search of higher paying gigs. So a handful of small businessmen, inventors, and audio engineers across central and West Kingston began to improvise a way to give the people the dance parties they craved without any live musicians. As small as they were, these parties would soon inspire some big advances in technology. And that tech was gonna help West Kingston’s nascent dance scene explode.

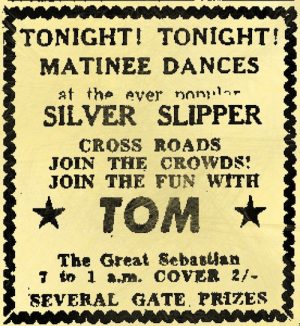

Right around 1950, a Jamaican inventor named Hedley Jones used his knowledge as a former radar engineer for the British Royal Airforce to build a new kind of powerful, dynamic amplifier. It was designed specifically for DJs. The amp had what’s called a “three-band equalizer” which could separate out and then emphasize high, mid, and low frequencies. Practically speaking, when you wanted a DJ to pump that bass, he now had the ability to do just that. A hardware store owner whose DJ name was Tom the Great Sebastian was one of the first to wire Hedley Jones’ new amp to his turntable and speakers. And he gave the powerful rig a new name: the sound system.

West Kingston’s dance scene expanded from cozy house parties to larger affairs in social clubs, empty buildings, and large open lawns. To keep all those people dancing, it now took a robust operation. And everything in the sound system just got bigger and bigger — the amps, the speakers, and the speaker cabinets. The meaning of “sound system” also expanded beyond the equipment itself. A “sound system” was also all the people it took to operate it — the owners, the DJs, and the engineers. By the early 50s, there were close to a dozen professional, top ranking sound system crews in and around Kingston. And these crews (sometimes just called “sounds” ) were locked in a full on technological arms race to see who could build the biggest rig.

Guys who were trained in electrical engineering and cabinetry mixed and matched imported equipment with miscellaneous spare parts, tinkering, soldering, hammering, wiring and rewiring … all on the quest to build amp and speaker units that pumped out sound so clear and so powerful it could crush every other DJ in town. As vital and impressive as the tech is, there was of course no “sound system” without the actual music. Records were the lifeblood of the sound. But while the early sound system operators had reconstructed their equipment to make it their own, virtually none of the actual music being played was Jamaican. And to get imported music, sound system crews found creative ways to get their hands on the records they needed. Many of them relied on men like Clement Seymour Dodd (who as a kid earned the nickname “Coxsone,” after a well-known British cricket player).

Dodd was a huge music fan. He was very familiar with these records, and he knew how to get more of them from the US. But he didn’t really play any instruments himself. He was a trained auto mechanic and carpenter — a left-brain technician with experience building speaker cabinets for other sound system crews, of which there were more and more each year. By the mid 50s, Kingston’s sound system dance scene was getting very crowded. Like Dodd, the guys who ran them came from all different walks of life. Dodd had been a migrant farmer and auto mechanic before finding his way to music. Early in his career, Coxson Dodd won battle-of-the-band-style clashes against veteran sound men like Duke Reid. Such victories were crucial because they helped establish Coxson as one of the best sound system operators in the game.

Dodd was a huge music fan. He was very familiar with these records, and he knew how to get more of them from the US. But he didn’t really play any instruments himself. He was a trained auto mechanic and carpenter — a left-brain technician with experience building speaker cabinets for other sound system crews, of which there were more and more each year. By the mid 50s, Kingston’s sound system dance scene was getting very crowded. Like Dodd, the guys who ran them came from all different walks of life. Dodd had been a migrant farmer and auto mechanic before finding his way to music. Early in his career, Coxson Dodd won battle-of-the-band-style clashes against veteran sound men like Duke Reid. Such victories were crucial because they helped establish Coxson as one of the best sound system operators in the game.

Winning sound clashes and throwing unforgettable dances was bigger than just bragging rights. In just a few short years, the sound system scene had become incredibly lucrative, supporting not just the sound crews, but security details, drivers, venue owners, and more. When it came to staying ahead of the competition, sound system crews could be relentless. At a clash, one crew might even stoop to sabotage, cutting speaker wires or starting fights just to derail the competition.

And there were other ways that DJ crews fought to stay on top. Lots of Kingstonians relied on the sound system parties to hear new music, for instance. Most people didn’t have record players, and Jamaican radio wasn’t playing the edgier party tracks they wanted to hear. So if that’s the kind of stuff one was looking for, one had to get out and dance.

The idea of authorship also started to change as the scene evolved. After erasing the name of the artist and their record label, sound men would sometimes even rename a newly anonymous tune. Then they’d drop the “new” cut at a party, and folks would go nuts. This whole process was one of the earliest iterations of a thing that would become really familiar in DJ culture: the one who got all the love for the music wasn’t the person who actually created it. It was the DJ. The props were for his skills in reading the crowd, his taste in music, and his access to the best dance cuts.

Easy Snapping by Theophilus Beckford is widely considered one of the first ska songs.

But then came rock and roll, exploding onto the music scene in the mid-1950s. With its pushy, whining guitars and no discernable dance beat, West Kingston’s party crowd was not feeling it. And as rock and roll became king in the US, sound men like Dodd found it harder and harder to get their hands on the bottom-heavy jazz and R&B that Jamaicans loved, and that sounded amazing on those giant speakers. It was time for something new. Dodd’s team was about to conceive a whole new, modern sound in Jamaica. t first, they called their shift in emphasis “upside down R&B.” It’s widely regarded as the first move into a new genre that would later be called “ska” — a style which echoes American R&B, but is clearly its own thing.

Alton Ellis’ Rocksteady is one of the first tracks to name the 1960s style that bridged ska and reggae.

In 1962, Coxson Dodd brought in some of Jamaica’s best sound system engineers, and they helped him build a production hub for the island’s music scene. Dodd named it “The Jamaica Recording and Publishing Studio.” But no one ever called it that. To the many famous artists who would record there, including Lee Perry, The Skatalites, and The Wailers, it was simply “Studio One.”

Larry & Alvin’s Nanny Goat is considered one of the first reggae songs recorded.

This was the early 60s, and Jamaica had just earned its independence. A strong current of black cultural pride and even black nationalism (led mainly by the explosion of the Rastafari faith) was sweeping the island. It became a definitive part of what local artists were recording, and now selling. Jamaicans were hearing themselves and their ambitions reflected back to them in their own music. The public couldn’t get enough. Jamaica now not only had its distinctive sound systems, but also a sound itself to call its own.

Leave a Comment

Share