The Seattle Underground by Avery Trufelman

Generally, residents have a very different experience of their towns and cities than visitors — by and large, locals don’t go to the tourist attractions that are in their backyard. This is true in the case of the Seattle Underground.

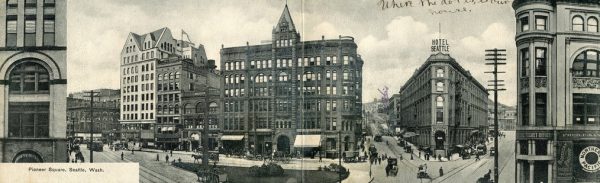

“The vast majority of our visitors are from out of town,” says Dean Nagarian, a tour guide with Bill Speidel’s Underground Tour, which allows you to descend some steps and find yourself underneath the city sidewalks. For about 20 blocks, within a district called Pioneer Square, the sidewalks are actually hollow.

“The vast majority of our visitors are from out of town,” says Dean Nagarian, a tour guide with Bill Speidel’s Underground Tour, which allows you to descend some steps and find yourself underneath the city sidewalks. For about 20 blocks, within a district called Pioneer Square, the sidewalks are actually hollow.

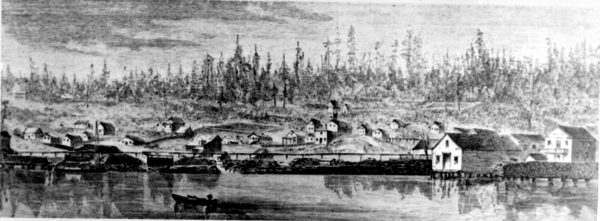

To understand why the sidewalks in Pioneer Square are hollow, one has to go back to when the first white settlers came to the area in 1851. The topography of the region was completely different back then: the land that would one day become Seattle was once a tiny peninsula, which used to periodically flood into an island. It was a terrible place to build a city, but white settlers did it anyway, and Pioneer Square quickly became little logging town full of tiny wooden houses and a logging mill, located near the docks.

Of course, the flooding persisted, which created issues for plumbing. “The toilets were at sea level,” explains historian Alan Stein. “So the problem is at the time the tide came in it would blast water through, and sometimes the “toilets [erupted] with water.”

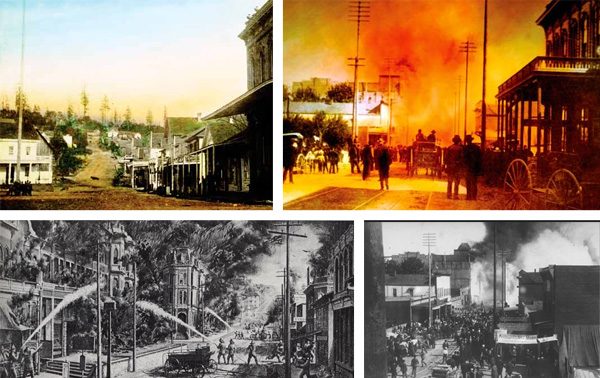

Nevertheless, life continued as the city grew… that is, until the entire downtown area essentially burned to the ground, during the Great Seattle Fire in 1889.

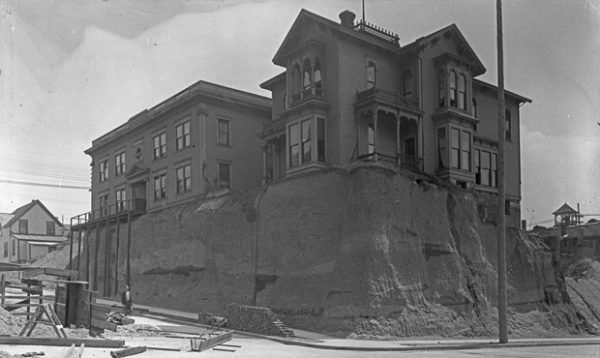

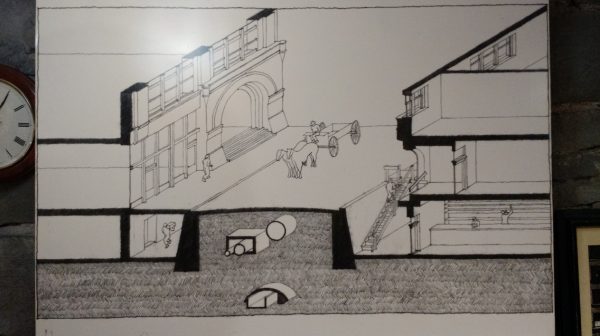

Miraculously, no one died in the Great Seattle fire. So the city saw this disaster as an opportunity to rebuild, and to get their town up above sea level. They decided to raise the streets over 10 feet above where the ground had been before. However, business owners in Pioneer Square were already rebuilding, and rather than halting the local economy while the streets were raised, business owners were told to rebuild using brick and to add another entrance on their second floors, anticipating the grade change.

The streets were being raised up, around the buildings and the sidewalks. In some cases, people had to go down stairs or up ladders to enter shops or businesses.

Eventually the city connected the raised streets to new second-story entrances with new sidewalks, creating a hollow space between the old sidewalk and the new one.

The resulting “underground” was rumored to have a lot of different uses. People have speculated about their lives as speakeasies, gay clubs, paths for espionage, or smuggling. In reality, though, a lot it was just abandoned or used as storage space by the shops above.

By the 1960s, businesses had started to leave Pioneer Square, which became down and out. In light of Seattle’s impending World’s Fair, there was a clamor to tear down Pioneer Square and build more modern structures, like the Space Needle.

The 60’s were a time when, according to historian Alan Stein, “People were more looking forward than they were to the past.” Except for a man named Bill Speidel, who was a columnist for The Seattle Times. Speidel was very interested in city history, and he had a lot of connections with children and grandchildren of some of Seattle’s founding families. Thanks to these old-timers, Speidel heard about the underground and the raising of the streets.

In 1965, Speidel started his tour company, in part to show Seattle residents that, even though they were a young city, that they had a history and a historic district that they were ignoring. Pioneer Square eventually got preservation status as a National Historic District.

Bill Speidel passed away in 1988, but today the area is packed with hoards of tourists, roving around in groups of 47 to take his tour — as many as 188 people come through every hour. The experience still very much continues in Speidel’s style: it’s more dedicated to fun than facts. There are a lot of gags and dad jokes about exploding toilets and the drunken debauchery on the raised streets.

A lot of things that get said on the tour can’t be verified and are likely exaggerated, but that’s true of many touristy tours: as facts and stories get repeated, the history can turn into a giant game of telephone.

In this case, though, without Speidel’s legends and dad jokes, this part of town might not exist at all. Although to this day, it’s a section of Seattle history that tourists know better than locals.

Comments (6)

Share

“auditory icons” are also called “earcons” – from reading “icon” as “eye-con”, and then making the analogy that, what an icon is to the eye, is that which an auditory icon is to the ear.

I really want to find a dictionary now in chronological order. Cant find one online. Anyone else?

Yea the website UI is pretty bad.

Blue Icon located on the left of a definition

https://www.merriam-webster.com/time-traveler/2010

Browse alphabetical is at the bottom of the page

https://www.merriam-webster.com/browse/dictionary

A great example of auditory icons is police radar detectors, Valentine brand in particular:

http://www.valentine1.com

They use different tones to signify the different frequency bands, and vary the beep frequency based on signal intensity. Coupled with visual direction icons, it’s a powerful system.

Episode 290 is a masterpiece!

#RomanMarsforPresident