It’s the most wonderful time of the year. It’s mini-stories season! Gather the kids around the fire because We have a year-end mix of short stories about a rogue architect, spooky kitchens, a hundred year old music streaming service, and the crazy way the French tried to make telling time less crazy. Let’s go!!!

The Decimalization of Time by Chris Berube

The French Revolution ushered in a whole lot of change — including (as part of this new, rational society they were building) a novel French idea called “decimalization”, which is a system of measurements that uses ten as the base number. They declared this an ingenious new idea …. Ignoring the fact that China had something similar to this up to the 17th century. And this whole system was about everything being neatly divisible by ten — time gone metric, as it were.

And it wasn’t just seconds, or minutes, or hours, but even days and months. There would be 100 minutes an hour, and a 100 seconds per minute, and just 10 hours per day, and so on. Of course, this meant things like the very length of a second changing fundamentally. The French introduced this along with a new calendar featuring ten-day weeks and this new timekeeping system in ten hour days in 1793.

And it wasn’t just seconds, or minutes, or hours, but even days and months. There would be 100 minutes an hour, and a 100 seconds per minute, and just 10 hours per day, and so on. Of course, this meant things like the very length of a second changing fundamentally. The French introduced this along with a new calendar featuring ten-day weeks and this new timekeeping system in ten hour days in 1793.

And it had a rather rough start. They kind of half-introduced as a new official system, with some of France switching over to this new system. But according to accounts from the time, only some people were using it, and even they were having a tough time getting adjusted to it. So to help ease this transition, they actually had these special clocks made that had both systems of time on the clock face. In the end, of course, the effort fizzled out, and the French use time like the rest of us.

There have been periodic calls to revive decimal-based time. It is appealingly logical, after all. But some changes may just be too big for people to stomach — like changing the length of a second. The human experience is as much about emotion as it is about rationality, and for things like this: minds are much more easily swayed by hearts.

Escarping Imprisonment by Kurt Kohlstedt

Many of the world’s most famous modern architects have something surprising in common: they never got their license to legally practice architecture. Even more surprisingly: some, like Le Corbusier and Frank Lloyd Wright, studied little to no architecture at all.

And that wasn’t terribly uncommon historically, and to some extent even today. Some designers don’t want to study for that test or get the prerequisite work requirements or meet those continuing education requirements. And learning on the job as an apprentice used to be a much more common path into architectural design. Today, architectural designers (who can’t call themselves architects, legally!) often work in firms where there are ‘actual’ architects on board who can look over and sign off on their drawings to keep things on the up and up.

But there was one famous historical (non-)architect, who practiced absent a degree or license, who eventually got into trouble for practicing. Carlo Scarpa was a 20th century Italian designer who, despite his lack of credentials, nonetheless worked in one of the richest historical built environments in the world: his hometown of Venice.

He shared certain aesthetics and approaches with regional Modernists like Alvar Aalto or Louis Kahn, who went beyond simple glass-and-steel boxes. He wasn’t a Modernist in the sense of someone obsessed with clean lines or straight and simple surfaces, creating neutral backdrops as foils for life and art. Rather, he was known for adding his own creative, and often quite bold and eccentric design elements to his rich historical surroundings. He would take creative liberties, deciding how to position and frame art in a museum, for instance, including what colors and material to use as backdrops, and even custom-designing pedestals for sculptures to sit on.

He shared certain aesthetics and approaches with regional Modernists like Alvar Aalto or Louis Kahn, who went beyond simple glass-and-steel boxes. He wasn’t a Modernist in the sense of someone obsessed with clean lines or straight and simple surfaces, creating neutral backdrops as foils for life and art. Rather, he was known for adding his own creative, and often quite bold and eccentric design elements to his rich historical surroundings. He would take creative liberties, deciding how to position and frame art in a museum, for instance, including what colors and material to use as backdrops, and even custom-designing pedestals for sculptures to sit on.

And much like our friends Le Corbusier and Wright, this guy with all of his creativity, didn’t get a license, but he was at least a little bit closer than those guys, for what it’s worth — he, at least, officially studied architecture! Nonetheless, after years of successfully designing buildings, he was eventually sued by the Venice Order of Architects for practicing architecture without a license. His career as he knew it was on the line — the stakes were high for all concerned.

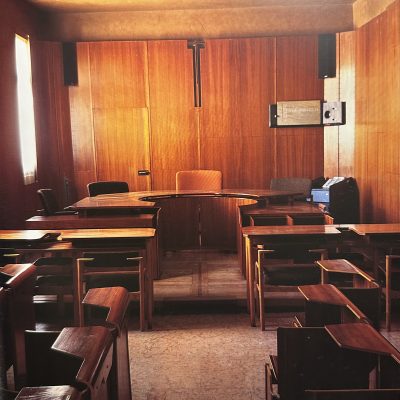

But then something remarkable happened. As the story goes: when the case wound up in front of the judge, it was in the courtroom that Scarpa himself had designed. And the judge essentially looked around the room, and said something to the effect of: it seems like this guy can do a pretty good job. Case dismissed! Apparently, even Scarpa’s own lawyer in the case went on to hire him to design his home. The courtroom itself wasn’t anything particularly crazy — just a very thoughtful mid-century design with a careful attention to materiality and details, from the door handles to the edges of wooden seats.

So Scarpa went back to work, and kept up his signature brand of quirky creativity up until he died at the age of 72 … but with a final design that would follow him to the grave. He designed his own burial plot, and he incorporated a drainage hole into the lid of the coffin cover. Visitors paying their respects were encouraged to come share a glass of wine with him after he had passed away — pouring one out for him, and down into this drain, to give him a drink. In any case, Scarpa is perhaps one of the most influential and compelling designers of the 20th Century. If you aren’t familiar with his work, you should check it out!

Ghost Kitchens by Delaney Hall

“Ghost kitchens” go by various names — they’re sometimes known as dark kitchens or virtual kitchens or cloud kitchens. And they’re a relatively new trend in the restaurant industry that seemed to really take off during the pandemic, rising along with the popularity of delivery services like DoorDash and Uber Eats. And the basic idea is that they are kitchens that specialize in delivery only. They do not have a storefront. They do not have servers. They do not have a place. You can’t walk in and sit down. They only sell food through delivery apps. And the more you learn about them, the stranger they get.

There are a few different types of ghost kitchens. One type is a kitchen that makes food for a bunch of different, “restaurants” that all have different identities and names. And those restaurants are basically hanging their digital shingle out on services like DoorDash or UberEats. And they might appear to be different restaurants, but the reality is that all their food is cooked in the same ghost kitchen.

Some of these operations are smaller and independent, but there are big players involved, too, with deep connections to the tech industry. So Travis Kalanick, the former chief executive of Uber, has been working on Cloud Kitchens, which is a ghost kitchen startup, for example. There’s also Reef Technology, a startup that includes multi-brand kitchens. This is very much a world where restaurants meet tech.

Some of these operations are smaller and independent, but there are big players involved, too, with deep connections to the tech industry. So Travis Kalanick, the former chief executive of Uber, has been working on Cloud Kitchens, which is a ghost kitchen startup, for example. There’s also Reef Technology, a startup that includes multi-brand kitchens. This is very much a world where restaurants meet tech.

And this trend is also intersecting with traditional brick and mortar restaurants in interesting ways. There’s another type of ghost kitchen that actually runs out of existing restaurants. Some of the most popular chain restaurants out there – places with actual restaurants you can eat at – have decided to cash in on this ghost kitchen trend. To do so, they’ve created new delivery-only restaurant brands – that they’re running out of their existing chain kitchens.

And this trend is also intersecting with traditional brick and mortar restaurants in interesting ways. There’s another type of ghost kitchen that actually runs out of existing restaurants. Some of the most popular chain restaurants out there – places with actual restaurants you can eat at – have decided to cash in on this ghost kitchen trend. To do so, they’ve created new delivery-only restaurant brands – that they’re running out of their existing chain kitchens.

But it’s not always clear to consumers that the delivery-only brand is affiliated with the chain. Pasquale’s Pizza and Wings? That’s really a rebranded face for Chuck E. Cheese! Pardon My Cheese Steak? An alternative operation of The International House of Pancakes. IHOP also operates under Thrilled Cheese, Super Mega Dilla, and Tender Fix.

So ghost kitchens are enabling chain restaurants that have a very fixed identity to do something different under various surprising alter egos. It’s like a chance to reach radically different markets than the ones that you might actually reach through your brick and mortar restaurants. So you can essentially disguise who’s behind a certain operation — and the connotations of a place like IHOP.

So ghost kitchens are enabling chain restaurants that have a very fixed identity to do something different under various surprising alter egos. It’s like a chance to reach radically different markets than the ones that you might actually reach through your brick and mortar restaurants. So you can essentially disguise who’s behind a certain operation — and the connotations of a place like IHOP.

So to recap: there are ghost kitchens operating multiple delivery only brands out of one commercial space. And there are big restaurant chains who’ve developed these delivery-only alter egos. But there’s one last example of a ghost kitchen, too, which is exceptionally strange: digital brands that hire out production to existing kitchens. For example, Mr. Beast Burgers, spun up by famous YouTuber Mr. Beast, has no restaurants or dedicated kitchens — instead, they partner with a company that specializes in connecting brands like his with kitchens. The result is that Mr. Beast Burgers are made in various commercial or local or restaurant kitchens. There are more than a thousand locations listed on the Mr. Beast Burger website.

And this highlights one of the tricky elements of being a virtual restaurant. Because Mr. Beast Burger has outsourced all of the food buying and food making to partner restaurants, consistency and quality control has been issues. Some customers have had really good experiences with burgers, but other people have had bad experiences, complaining about the presentation being bad, with burgers arriving and random packaging. Or worse: some have claimed they were delivered uncooked food or burgers on moldy buns. Mr. Beast, for his part, is now suing his distribution partner. And they’re suing him back.

And this highlights one of the tricky elements of being a virtual restaurant. Because Mr. Beast Burger has outsourced all of the food buying and food making to partner restaurants, consistency and quality control has been issues. Some customers have had really good experiences with burgers, but other people have had bad experiences, complaining about the presentation being bad, with burgers arriving and random packaging. Or worse: some have claimed they were delivered uncooked food or burgers on moldy buns. Mr. Beast, for his part, is now suing his distribution partner. And they’re suing him back.

These something inevitably deceptive about the whole “ghost kitchen” concept. Our old-fashioned expectation of a restaurant is that it is a place staffed by people who are trained to create a particular kind of food — that there’s just this single integrated entity responsible for the quality of what I’m about to eat. With ghost kitchens, it’s just different. It might be a commercial kitchen appearing to be lots of different “restaurants.” It might be a Chucky cheese masquerading as a Pasquale’s. Or it might be an Italian chain making hamburgers for an unrelated brand and slapping a logo on it.

The Original Streaming Service by Talon Stradley (Read by LeVar Burton)

For a monthly fee, you could simply pick up your phone and hear an entire orchestral performance. Only, it wasn’t an orchestra. It was a single instrument, doing its best impression of an orchestra. It all begins with the telharmonium’s inventor, the ever curious Thaddeus Cahill, who was reserved, studious and incredibly smart. As early as 13 he was experimenting with music sent over telephone wires, an idea that would later become the Telharmonium. When he was just 18 years old, he filed his first patent. Many more would follow as he worked to improve devices like typewriters and pipe organs. He soon set his ambitions higher to develop a machine that could meticulously control the very shape of a soundwave. While other instruments used air or strings to produce their tones, Cahill turned to something new: electricity. He began working on the ultimate instrument which Cahill patented in 1897 when he was 30 years old. This instrument would be able to perfectly replicate any other sound on Earth.

For a monthly fee, you could simply pick up your phone and hear an entire orchestral performance. Only, it wasn’t an orchestra. It was a single instrument, doing its best impression of an orchestra. It all begins with the telharmonium’s inventor, the ever curious Thaddeus Cahill, who was reserved, studious and incredibly smart. As early as 13 he was experimenting with music sent over telephone wires, an idea that would later become the Telharmonium. When he was just 18 years old, he filed his first patent. Many more would follow as he worked to improve devices like typewriters and pipe organs. He soon set his ambitions higher to develop a machine that could meticulously control the very shape of a soundwave. While other instruments used air or strings to produce their tones, Cahill turned to something new: electricity. He began working on the ultimate instrument which Cahill patented in 1897 when he was 30 years old. This instrument would be able to perfectly replicate any other sound on Earth.

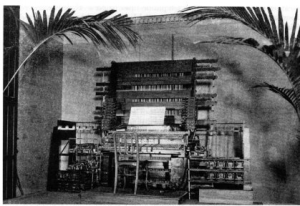

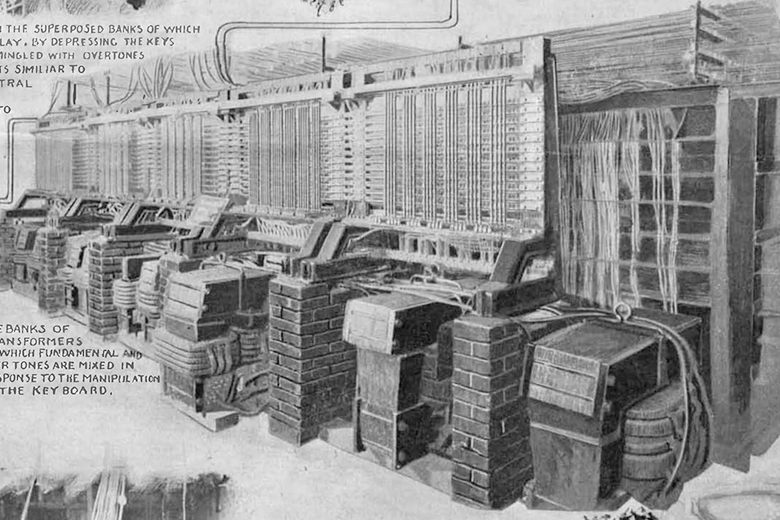

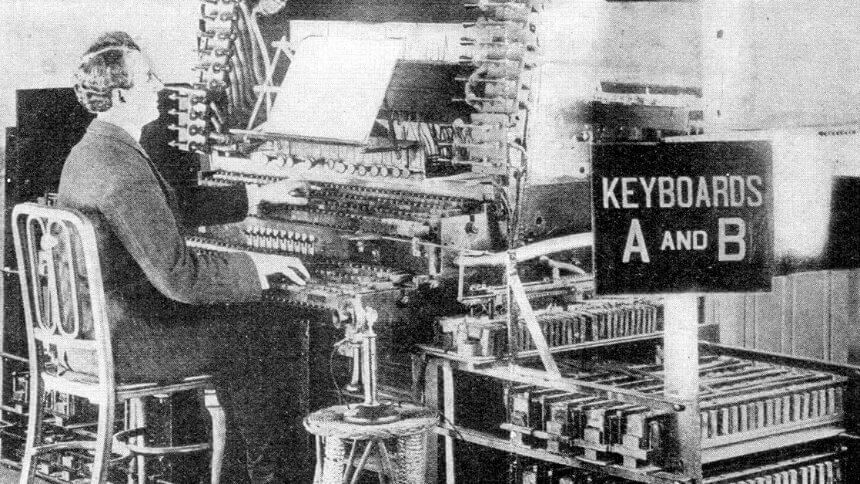

The telharmonium was massive. It looked less like a grand piano or a cello, and more like a power plant with 200 tons of large steel boxes and wires. It was a machine designed to play with the building blocks of sound. You can think of it like a painter’s palette. The fundamental note is like a primary color – think red, blue, or yellow. Overtones are much quieter notes that play alongside the fundamental. These are the subtle shades that give depth and complexity. Each instrument accentuates different overtones, giving you different sounds. This is part of why a piano sounds different than a violin, even if they’re playing the same note. Cahill wanted to shape exactly which overtones we were hearing, allowing him to recreate any musical instrument he desired.

He started with sine waves, the absolute purest form of sound. They contain no overtones, just the fundamental note. The telharmonium uses tonewheels– massive cogs that spin at the frequency of the pitch– to create these sine waves. Each note of the telharmonium had a tonewheel for the fundamental note and up to 20 more for the overtones. This was all made a few years before the amplifier, meaning the Telharmonium had to create an electrical current so strong that it wouldn’t need to be amplified. To make that many notes that loudly required a large, and expensive, machine.

Cahill built a prototype and organized a demonstration. He played Handel’s Largo for an audience of potential investors. The businessmen were amazed. With his project funded, Cahill constructed a full scale telharmonium at his factory in Holyoke, New Jersey. It cost around $200,000 – over $7,000,000 when adjusted for inflation. After its completion, the telharmonium was shipped from Cahill’s New Jersey factory to its new home in Manhattan. It was set up in a building across from the Metropolitan Opera house, called: Telharmonic Hall. The machine’s mechanics were housed in the basement, connected by wires to keyboards in the auditorium.

The debut of Telharmonic Hall in 1906 was a roaring success. Demand was so high, they doubled their daily shows and had to open up the basement to fit more visitors. One notable fan of the telharmonium was author Mark Twain who wrote: “Every time I see or hear a new wonder like this I have to postpone my death right off. I couldn’t possibly leave the world until I have heard this again and again.”

Part of Cahill’s plan was a bold new idea: a musical subscription service. Telharmonic wires were strung up alongside telephone wires and subscribers could pay a monthly fee to listen at home on their phones. And at least one hotel was constructed with Telharmonic service available in every room. However, despite its novelty, there were a number of problems that plagued the telharmonium. While some described it as “pure of pitch” and with a “soothing quality”, others complained that it was “rather crude and lacking in variety.” It was also hard to play, requiring two people to operate keyboards that were completely different from a piano or an organ. The business was impossible to scale. Each new subscriber required more electrical power. Eventually the only way to keep up with demand would be… to build an even bigger machine. The phone companies weren’t too happy either. The telharmonic music and regular phone calls ran on neighboring wires, and the much stronger telharmonium signal would loudly bleed over and provide unexpected background music. In one anecdote, a woman suspected her husband was lying and calling from some concert hall instead of his office.

All of these challenges were made even worse by the financial crisis of 1907. Subscriptions fell, and the attendance was so low that Telharmonic Hall dropped performances to just once a day. The final show at Telharmonic Hall was on February 16th, 1908, its bright but brief time in the spotlight lasting not quite two years.

Cahill tore down the telharmonium and retreated back to Holyoke. He began working on a cheaper and more efficient third model. In 1911, Cahill spent 5 months disassembling, transporting, and reconstructing this third Telharmonium in New York, this time connecting it to Carnegie Hall. It received little fanfare. Both the press and the public were no longer interested in dial-up music, thanks to a new invention – the radio. A few years later, Cahill’s company filed for bankruptcy with over $100,000 in debt – nearly 3 million dollars today. All three telharmoniums were eventually sold for scrap.

Cahill died in 1934. That same year, the Hammond organ was invented, which used tone wheels coupled with newly-developed amplifiers to make a similar– and much more manageable– instrument. It also used overtones to imitate pipe organs, but at a fraction of the size. It was intended for churches, but then broke out as a staple of rock, soul, and blues music. While the sound of the telharmonium may have disappeared, its influence can still be seen today. Synthesizers and other electronic instruments have made it easy to have an entire orchestra at your fingertips. Still… one can’t help but imagine the enchanting sound of the Telharmonium.

Cahill died in 1934. That same year, the Hammond organ was invented, which used tone wheels coupled with newly-developed amplifiers to make a similar– and much more manageable– instrument. It also used overtones to imitate pipe organs, but at a fraction of the size. It was intended for churches, but then broke out as a staple of rock, soul, and blues music. While the sound of the telharmonium may have disappeared, its influence can still be seen today. Synthesizers and other electronic instruments have made it easy to have an entire orchestra at your fingertips. Still… one can’t help but imagine the enchanting sound of the Telharmonium.

If you and your kids want to help LeVar find missing sounds, be sure to check out his new podcast, Sound Detectives. You’ll meet Detective Hunch and Audie, a literal walking talking human ear. You may also hear a familiar voice. Let’s just say, I think I’d be a pretty great flight attendant. The first season of Sound Detectives is out now wherever you get your podcasts.

After we come back from our holiday break, we’ll have even more mini-stories for you! But if you’re bored and looking for some to listen to, we also have sixteen (!!!) volumes from years’ past. Check ’em out!

Leave a Comment

Share