For the 500th episode of 99% Invisible, we started thinking about the kinds of designs that we love from the places we have lived — and even some regional vernacular we love from places we haven’t lived, but just admire. 99% Invisible is all about who we are through the lens of the things we build. We often tell stories about how people shape the built world, but these are more about how the built world has shaped us.

Dingbats by Vivian Le

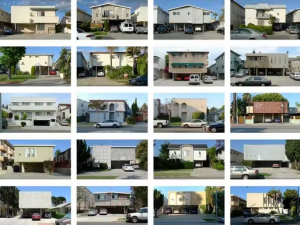

Los Angeles is full of iconic structures, like the the Hollywood sign, perched on the hills and somehow shining through the smog, or the Santa Monica pier for fans of sunshine and waterfront vibes; or even the strange Googie-style “Theme Building” at LAX. But for producer Vivian Le, the first thing that comes to mind is the Dingbat.

These are a type of low-rise multifamily apartment building that typically has a half-dozen or so units. Most have completely flat roofs, but their defining feature is their tuck-under parking — on one side of the building, there are parking spaces carved out of the first floor, with units behind and on top, which helps make the structure look like a box propped up on skinny stilts from certain angles. These denser configurations were designed to address the post-WWII housing boom.

Dingbats were generally cheap and tacky, and when zoning regulations and building codes phased them out of production, not many people gave it much thought. But there is a lot to love and a lot to learn from dingbats. They helped make a seemingly inaccessible city a little more accessible to hundreds of thousands of residents who couldn’t afford single-family homes, but wanted that little bit of autonomy that outdoor corridors and separate slices of driveway provided.

A-Frames by Alexandra Lange

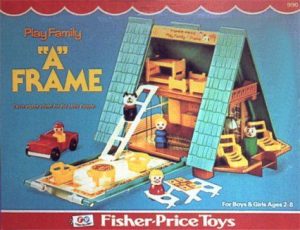

As a child, design critic Alexandra Lange had a peculiar kind of dollhouse — not the typical boxy Victorian, but rather a fold-down A-frame made by Fisher Price. With facades aptly shaped like giant letter “A”s, these structures have become associated with everything from Swiss ski chalets to cabins along rural American lakes. They are simple and iconic, and in some ways quite universal: tents are, in a sense, basically A-frames.

As a child, design critic Alexandra Lange had a peculiar kind of dollhouse — not the typical boxy Victorian, but rather a fold-down A-frame made by Fisher Price. With facades aptly shaped like giant letter “A”s, these structures have become associated with everything from Swiss ski chalets to cabins along rural American lakes. They are simple and iconic, and in some ways quite universal: tents are, in a sense, basically A-frames.

“The A-frame, in its purest sense, is a house shaped like an equilateral triangle,” writes Lange. “Its distinctive peak is formed by rafters or trusses that are joined at the top and bolted to plates or floor joists down below. The roof covers the rafters and goes all the way to the ground. The cross-piece of the A is created by horizontal collar beams, intended to stabilize the structure, which support a sleeping loft.”

But while A-frames can be aesthetically pleasing and conjure associations with vacations, they are not the most practical buildings to use as a primary dwelling. The steeply sloped roofs make for less livable space, and families often have to cram together in the resultingly cramped area — all fun and games for short trips, but not necessarily optimal for everyday living.

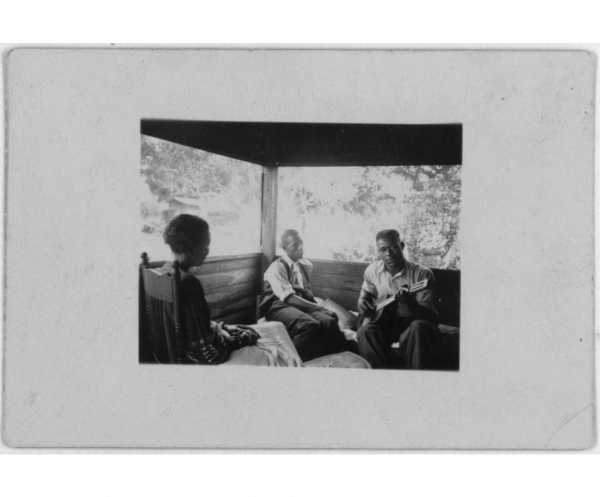

Southern Front Porches by Christopher Johnson

Growing up, 99pi producer Christopher Johnson would head down to the country to visit his great grandmother, who lived alone in a small farmhouse in rural North Carolina. In the evenings, they would spend time together on her front porch, enjoying the breezes and the sounds of nature.

The front porch is an iconic piece of Southern culture. Writers including Zora Neal Hurston, William Faulkner, Alice Walker, and Harper Lee have used the front porch to describe what’s challenging, mystical, and beautiful about life Down South. The rapper Juvenile centers one of his first videos around front porches in his New Orleans neighborhood. In the “signature shot” from Lemonade, Beyonce featured the front porch.

Porches can also be complicated spaces, somewhere between public and private, jutting out into the world but also reserved for more familiar guests. When it comes to race, front porch social rules can get nasty, with Blacks being told to go around backs of homes owned by whites. There’s a long history of controlling Black labor and leisure in the US, and there have been real efforts to restrict, police, and shame those who want to gather and relax on their own porches, too.

Porches can also be complicated spaces, somewhere between public and private, jutting out into the world but also reserved for more familiar guests. When it comes to race, front porch social rules can get nasty, with Blacks being told to go around backs of homes owned by whites. There’s a long history of controlling Black labor and leisure in the US, and there have been real efforts to restrict, police, and shame those who want to gather and relax on their own porches, too.

In a way, the American front porch have always been fraught. Its history is rooted in the Transatlantic Slave Trade. The front porch typology that was adopted in the US can be traced to precolonial West Africa, where people built elevated porch-like structures onto their homes as places to conduct business and cool off. European explorers took note, since there was nothing quite like the African front porch in Spain, Portugal, France, or England.

In a way, the American front porch have always been fraught. Its history is rooted in the Transatlantic Slave Trade. The front porch typology that was adopted in the US can be traced to precolonial West Africa, where people built elevated porch-like structures onto their homes as places to conduct business and cool off. European explorers took note, since there was nothing quite like the African front porch in Spain, Portugal, France, or England.

When those Africans were enslaved, they brought this building typology with them via The Middle Passage, drawing on their expertise as they constructed homes throughout the hot, humid Caribbean. And then around the late 1700s, the front porch jumped from the West Indies into what eventually became the United States. The Haitian Revolution played a huge role here, because it sparked a massive migration to Louisiana Territory. And that’s where Haitians introduced the shotgun house, and — its front porch. Caribbean porch design also entered the US by way of southern Florida, and Charleston, South Carolina.

Starting around the 1860s, front porches began spreading way beyond the South. Popular home design books, new building techniques, and a movement in architecture focused on nature and landscapes all helped make the front porch super trendy across the country.

Slavery and war helped bring the front porch to the US, and it was the end of war that brought on the porch’s decline. A post-WWII rush to build more housing in less time and with less space made front porches impractical.

But what really did the porch in was air conditioning. By the ’60s, AC was pretty common in American homes. Today, porches are less common than they were, but for many, they remain a vital part of a slower-paced life dovetailed with nature.

Leave a Comment

Share