When the pandemic hit, everything that could possibly be done online made the jump — work, job-hunting, school, doctor’s visits, and so on. The shift was hard for everyone, but many Americans didn’t even have the fundamental thing needed to make that change: a fast and reliable internet connection.

People without internet access showed up at emergency rooms — during a pandemic — for non-emergencies, because they just weren’t able to do a video appointment. And when the time came, there was no refreshing a browser to find out where to get a vaccine. And the lack of access isn’t just in rural areas, as is often assumed. About one in five people in New York City don’t have any internet access at all — not even through data on their cell phones.

We’re two decades into the 21st century, yet when it comes to life online, large segments of America are still living in the 1900s.

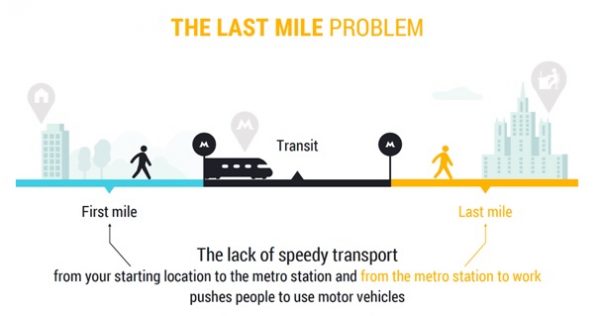

To understand why, one first needs to understand how the internet works. In simple terms: there are multiple tiers, including large backbones that span countries and oceans, “middle mile” tiers connecting regions and cities — both which use high capacity fiber lines. But then there is the third tier, where it gets to end users — or in many cases: where it doesn’t get to them.

The “last mile problem” is where things get stuck, because of all of the nit-picky and local work that goes into connecting lines to buildings, or digging up roads to bury wires. This is the challenging and costly part. So instead of fiber, most people’s internet is traveling that last mile over wires that were first laid for totally different purposes — which is why a phone company like AT&T may also be your internet provider, because you’re using the copper lines originally provided for your phone connection or the coaxial lines normally used for your cable TV.

While something like dial-up might mostly be a thing of the past, the truth is copper phone lines still connect a lot of people to the internet over DSL. And even many people’s coaxial cable connections aren’t fast enough to meet the federal government’s definition of broadband (25 megabits per second download speed, and 3 megabit upload). Who gets fiber is determined by the market, and the market is determined not by who wants fiber, but really just who can already afford it. So for a lot of the country, the last mile remains a deep and vexing problem. Different cities have tried to solve that problem in different ways:

Detroit, Michigan

Back in 2014, Detroit was ranked as the country’s worst connected city — around 60% of people didn’t have a connection that met the minimum definition of broadband, and 40% had no internet at all. In some cases, people weren’t able to get online because there wasn’t an affordable option. In others, there was simple no tier 3 infrastructure. Often, this is the result of what’s called “digital redlining” — a phenomenon that can be found in cities across the country. Even where service was available, it was often anything but fast. Programs to help low-income households provided painfully slow speeds.

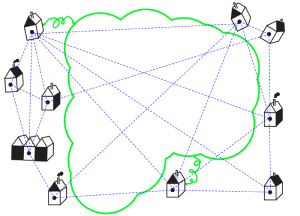

To work around the problem, some folks in certain neighborhoods began sharing connections — not just passwords, but mesh networks. This technological approach offered a way to bring wireless internet to a whole bunch of people all at once, using old routers and signal extenders to share service from better-connected homes to other residents. Relay nodes began popping up on all kinds of structures, and many residents left their networks intentionally open so they could serve as part of the mesh. This became a ground-up solution for a top-down problem.

There was a slight catch, however: it turned out that this wasn’t exactly legal. On the upside, this spurred community initiatives like Detroit’s Equitable Internet Initiative to contract directly with tier 2 providers, going around traditional tier 3 companies and providing broadband services to hundreds of homes in multiple neighborhoods. The mesh works have, in effect, become the third tier in places. But even some mesh network fans aren’t sure about the scalability of this solution.

Chattanooga, Tennessee

Back in the mid-2000s, Chattanooga was a bit like Detroit, with limited internet access options for most telecom customers. Then the city decided that starting in 2008, EPB, the local public power utility, should enter the telecom market and become an internet provider, meaning EPB would compete with the existing providers to sell internet connections to businesses and households.

EPB already had power lines that reached every home and business in town, meaning they could put these super-fast internet lines right alongside them. And so EPB started laying down fiber all over the city. This sparked a war with the existing private providers to provide faster and faster speeds. At first, these speeds almost excessive, but of course over time they paid off.

The idea was that even if EPB didn’t dominate the market, they would foster competition and force the private companies to provide better services. And that is, in fact, what happened. It’s also easy for new customers to adopt EPB’s services, since all the cables are already in place. EPD also provides at-cost service to low-income families, creating greater access equality.

Economists predicted that city-wide fiber would stimulate the addition of 2,000 jobs over ten years. According to some studies, it’s actually added about 10,000 jobs. Not long into the pandemic, the surrounding county’s unemployment rate was 2% lower than the national average. Treating broadband as a public good did great things for the public.

The Future of Broadband

One might hope to use this city as a template for other urban areas, but Chattanooga has some distinct advantages, such as: its own municipal electric system, allowing them to use their own existing infrastructure. But there’s a bigger problem, regardless: in eighteen states, for-profit company lobbying has helped legislature pas legal roadblocks that hamper municipal internet efforts. Their argument is that the government would stifle competition. As a result, in many states and cities and rural areas, private ISPs are the only ones allowed to provide these services — including Detroit.

Barring changes to state and local laws, it is hard to see an obvious path toward better access in many places. Ultimately, it’s going to be tricky. The goal of for-profit companies will always be to make money, which is why a lot of people still believe that quality internet access for everyone means eventually treating broadband as a right, not just a commodity. That will require intervention by people who are accountable to votes and not just the bottom line.

Reporter Katie Thornton produced this story for 99% Invisible. Be sure to check out her Instagram for more about broadband infrastructure, including the story of the ‘Empire City Subway’ (and no, it’s not a train, but rather a really exciting tunnel stuffed with wires).

Comments (3)

Share

Great episode. Excellent background on how the internet gets to everyone. As a believer of ‘internet as a right’ while also working in technology, this episode was particularly interesting. There’s a small but thriving global network of public internet exchanges (IX’s) who voluntarily exist to support the ideals you reported on. As a board member of my local exchange, we work at the intersection of for-profit and public networks, and your reporting really resonated.

Appreciate you covering this topic, and good background work on learning about all the different technologies. Even being in the industry, it’s sometimes tough to keep up.

Another great 99PI story, and why I am a subscriber and supporter. The Detroit portion of this episode is very familiar as it sounds a lot like our experiences in rural Louisa county in Virginia. Almost a decade ago the county government created a “broadband authority” to bring high speed internet to every house in the county. When the pandemic hit we were still working off of satellite internet and LTE connections.

In July 2020 Verizon ran a fiberoptic line across my front yard to a new solar farm down the road with an access box next to my driveway. I’ve asked them regularly to be hooked up, and when I checked yesterday (13 March 2022) the answer was still that service is not available at my address.

The issues of internet provider monopolies have plagued service for my father and daughter in Richmond, VA, Las Vegas, NV and Reston, VA as well.

It was good to hear about the success that Chattanooga had though, but it will be al long tome before Virginia catches up.

Thanks fore the great reporting and storytelling.

David Critics

I found this very interesting, as I do all of your episodes. But I was particularly interested because there is a company in the bay area that is using the mesh network as their product. They are competing with Comcast, AT&T. I found them when I got so fed up with poor service from Comcast and AT&T and was looking for an alternative. The company is Sail Network. My internet is fast, stable, and I haven’t had any problems since having it installed. I don’t know if they have special pricing for low-income. I hope more companies like Sail can give Comcast & AT&T good competition, which will hopefully encourage more choices, lower costs, etc.