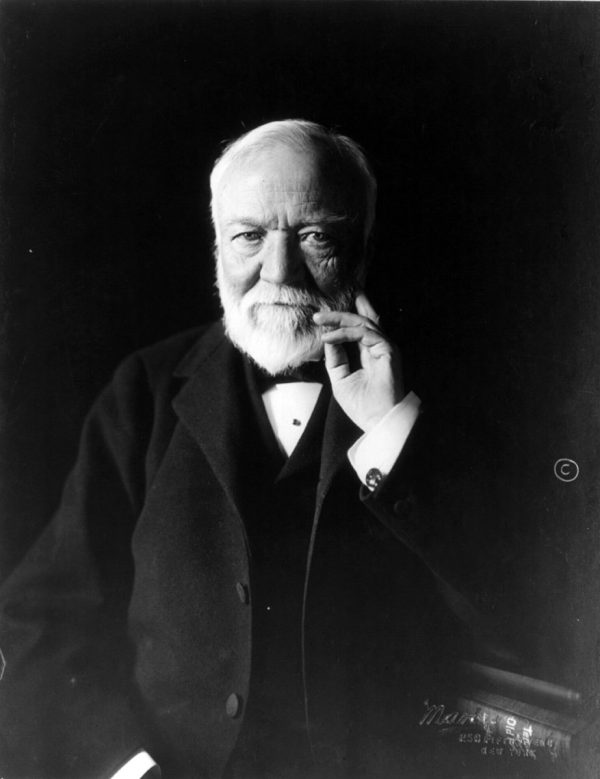

Eric Klinenberg is the author of a book called Palaces for the People: How Social Infrastructure Can Help Fight Inequality, Polarization, and the Decline of Civic Life. The phrase “palaces for the people” actually comes from Andrew Carnegie who was known as a titan of the Gilded Age and one of the wealthiest people in the world when he lived.  Carnegie was a ruthless capitalist, famous for strike-breaking and doing things that promoted inequality in many parts of the world, but he was also an immigrant, and was committed to the idea that the US was a country where people could get ahead in life. Carnegie wanted to help build a social institution that would facilitate that.

Carnegie was a ruthless capitalist, famous for strike-breaking and doing things that promoted inequality in many parts of the world, but he was also an immigrant, and was committed to the idea that the US was a country where people could get ahead in life. Carnegie wanted to help build a social institution that would facilitate that.

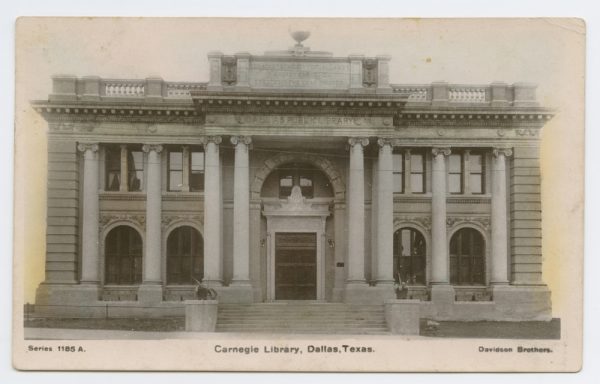

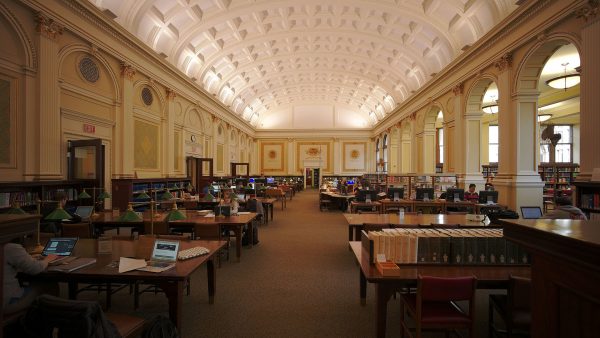

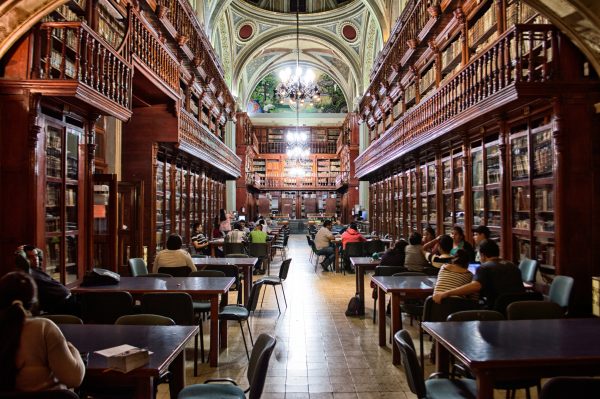

Over the course of his life, Carnegie helped to fund more than 2,500 libraries around the world—about 1,700 of which were in the United States. He called greatest of them “palaces for the people.” The great Carnegie libraries had high ceilings, big windows, and spacious rooms where a person could read, think, and achieve something that they felt proud of. Although it should be noted that these palaces were not always for everyone. Many of the great Carnegie libraries remained racially segregated throughout the early 20th century, and they later became battlegrounds in the civil rights movement.

Social Infrastructure

Social infrastructure is the glue that binds communities together, and it is just as real as the infrastructure for water, power, or communications, although it’s often harder to see. But Eric Klinenberg says that when we invest in social infrastructures such as libraries, parks, or schools, we reap all kinds of benefits. We become more likely to interact with people around us, and connected to the broader public. If we neglect social infrastructure, we tend to grow more isolated, which can have serious consequences.

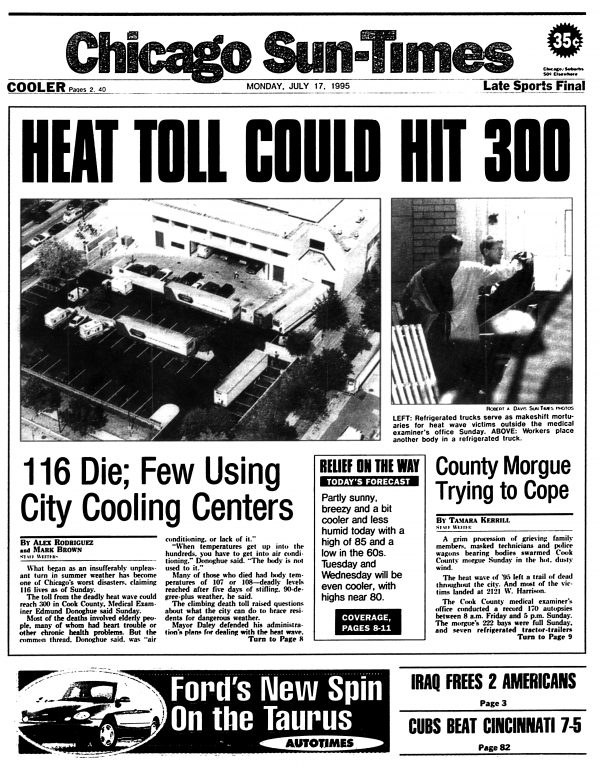

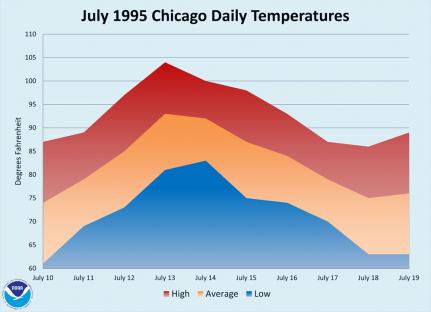

The first time Klinenberg thought about social infrastructure was when he was a graduate student doing a research project about a terrible heat wave that took place in Chicago in 1995. It was a disaster that killed more than 700 people, and as a social scientist, Klinenberg was interested in understanding the patterns that emerged from it.

The first pattern he observed was the most predictable, which was that poor or segregated neighborhoods on the South Sides and the West Sides of Chicago had the highest death rates by far.

But when Klinenberg looked more closely at the patterns, something really puzzling emerged. There were a number of working class neighborhoods that demographically appeared as though they should have fared very badly in the disaster, but actually proved to be strikingly resilient, and even safer than some affluent neighborhoods on the North Side.

Even more interesting, there was a pair of neighborhoods where the demographics were identical. Each neighborhood had the same proportion of old, poor, and African-American people, and was separated by just a street. They were literally neighboring neighborhoods, but one had an astronomically high death rate and the other was one of the safest places in Chicago.

Klinenberg started spending time in the neighborhoods, and what he observed was that the places that had low death rates turned out to have a robust social infrastructure. They had sidewalks and streets that were well taken care of. They had neighborhood libraries and community organizations, grocery stores, shops, and cafes that drew people out of their home and into public life. What that meant was that on a daily basis, people got to know each other pretty well and used the social infrastructure to socialize. When this heat wave happened in Chicago, neighborhood residents knew who was likely to be sick and who should have been outside but wasn’t. This meant they knew whose door to knock on if they needed help.

Meanwhile, in the neighborhoods that had really high death rates the social infrastructure was depleted. There were a lot of abandoned properties, empty lots, and abandoned houses. Sidewalks were often cracked and broken and there was very little commercial life. This all meant that people were likely to stay home, and this was a deadly thing to do during a heatwave.

Carnegie Probably Didn’t See This Coming…

Years later Klinenberg was working with designers in New York who were thinking about how to respond to Hurricane Sandy. One day Klinenberg was taking one team around a neighborhood in Brooklyn, and they had an idea for something called a “resilience center.” This resilience center was going to be a nice building staffed by welcoming personnel and was going to have all kinds of special programming for kids, and access to Wi-Fi and computers. What they didn’t realize was that they were basically just describing a library, which offers all of those same resources. Klinenberg came to realize he needed to remind people of the extraordinary things that libraries do as social infrastructure that is taken for granted.

Photo by Kai Hendry (CC BY 2.0)Libraries still remain places where lots of early literacy development happens. Libraries have also now become the places where formerly incarcerated people come more to search for jobs or receive help on their resumes. Carnegie probably would not have anticipated that libraries would become the places where there’s more instruction for English as a second language or more citizenship classes than any other public institution. He wouldn’t have seen all the teenagers coming to the library at the end of the school day to play games, or just because it’s the safest and warmest, or just to play games.

Libraries have reinvented themselves, and one of the things that is so striking about them is that the local staff has the capacity and agency to develop programming that works for the community that they’re in. The library can lend tools and it can lend clothes to people who need better clothes for a job interview. It can do programming and all kinds of languages.

The design of a lot of libraries have been able to evolve along with communities they serve, such as allowing special separated spaces for teenagers who could possibly be disruptive to others sharing the space. Although many libraries have the potential to better serve the needs of their communities, many still lack the proper resources to do so.

Fixing the Broken Windows Policy

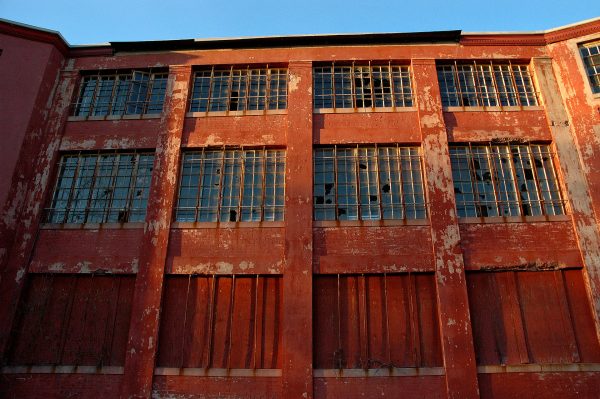

The broken windows theory of policing and crime is a classic essay by James Q. Wilson and George L. Kelling. It said that when there are broken windows in a neighborhood, people perceive the broken windows as a sign that no one is organizing the neighborhood — meaning those intending to commit crimes would feel like they could get away with it there.

The broken windows theory was used as a justification for bringing lots more police into poor neighborhoods. It led to stop and frisk policing and zero tolerance policing because of the belief was that if there’s disorder, then you need to make sure that there’s extra help to keep criminals from committing crimes. This was a big reason for why we have a system of mass incarceration that has transformed the United States, especially poor neighborhoods.

Having spent a lot of time thinking about the power of social infrastructure and physical places, Klinenberg asked himself this question: what would have happened if we had responded to broken windows not by sending in so many police officers, but instead by fixing the windows?

It turns out, someone at the University of Pennsylvania had been asking a similar question. This person teamed up with the city of Philadelphia which has tens of thousands of abandoned properties and empty lots. The Pennsylvania Horticultural Society started an exciting social science experiment, and for more than a decade have been making simple interventions to randomly selected blocks. If there was an abandoned house they would board up the building to prevent squatters or potential drug dealers from using the property, and mowed and maintained the yard.

The results were staggering — they achieved almost a 40 percent decline in gun violence around the abandoned properties that had been treated. What’s more, they hooked up heart rate monitors to people living in those neighborhoods and they found that heart rates spiked high when residents walked past an un-kept property. Stress-related diseases are especially high in poor neighborhoods that have a lot of abandonment, but when people walk by a property that’s been taken care of, their heart rate hardly changes. They also noticed that when crime reduced in the blocks with intervention, crime levels didn’t jump in other nearby neighborhoods as predicted.

Show Me the Money

When it comes to sources of social infrastructure like parks and libraries, one urgent question we should be asking is, “How are we going to pay for this?” Carnegie was a philanthropist, and his philanthropic dollars went into building a number of branch libraries. Today, it’s strange that we live in a world with titans of the information age, such as Mark Zuckerberg, who have made billions of dollars off of social media and computing but haven’t made contributions to social infrastructure in a meaningful way. Zuckerberg’s use of the concept of social infrastructure has been promoting the platform Facebook as social infrastructure. He believes that Facebook is where people should go for meaningful social interactions.  Klinenberg points out, though, that if you go to the Facebook campus in Menlo Park, the amount of money Zuckerberg has put into physical structures of social infrastructure for his employees is astronomical. There are bike paths, and yoga studios, and shared spaces for serendipitous encounters.

Klinenberg points out, though, that if you go to the Facebook campus in Menlo Park, the amount of money Zuckerberg has put into physical structures of social infrastructure for his employees is astronomical. There are bike paths, and yoga studios, and shared spaces for serendipitous encounters.

On one hand, Klinenberg wants to see the philanthropists of our time spend more money on things like libraries, but he also knows that philanthropic dollars are ultimately inadequate and randomly distributed to the places where the philanthropists spend their own time. If we’re ever really going to make this work, it’s going to have to be through a public commitment such as a major public works program.

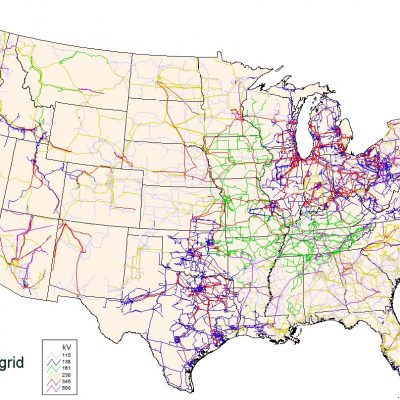

Reports from the World Bank or our own government, they recognize that we will soon be spending trillions of dollars internationally to build new infrastructures like subway systems or power grids because the systems that we have to keep us in the modern world simply don’t work. Klinenberg’s observation is that the same is true in the case of our social infrastructure because they’ve been absolutely neglected. If we want to support the kind of social life that we all need, then we’re going to have to invest in it.

Comments (16)

Share

Thank you for this episode. There are so few municipal establishments that are open to the public anymore. There are so few places that are indoors that you can go and hang out, and take a rest, maybe learning something without having to buy something. Horrible to think that anyone would have the gall to name libraries as obsolete. Libraries are our tax dollars at work for once!

Listening to Americans discussing public space is like comedy!

This episode is high quality and the best thing I´ve heard in a long time.

I really wish there were versions of this text, in other languages, because it is a topic of great public interest.

Hi Christina – that is so kind of you! Unfortunately, we don’t have the text in other languages but you could try using an online service such as google translate. Thanks for listening!

Thank you so much for doing this podcast on Palaces for the People! When my children were little and we had no money, the library was our escape. We were there at least once a week, and often more frequently than that. I still remember checking out Nina Laden’s “When Pigasso Met Mootisse” for my son over and over again because every time we had to return it, he would ask for it again. Not only were we able to check out books from our library, we could also check out movies, fishing poles, and video games.

We have moved a few times since their toddler days, but the first thing we do when we move to a new town is get a library card to the local library.

Thanks again for reminding everyone what a valuable resource our libraries are!

This episode made me wonder, how different is the concept of “social infrastructure” from the concept of the commons, and their enclosure which is driven by capitalism? Silvia Federici and others have written quite a lot about it. The enclosure of the commons in 16th century Europe is often cited as the beginning of modern capitalism. Isn’t the enclosure of the commons the same as making social infrastructure less robust? I find it strange the author isn’t more overtly critical of capitalism, because capital drives the enclosure of common spaces, making us more isolated, more vulnerable, more exploitable.

Thanks for making one of my favorite podcasts!

I support libraries 100% and this episode is fabulous. Its amazing that you need an academic to tell you that as humans the most important capital we have is our humanity.

And yes is that what in the worse case scenario (re:heatwave )will determine your fate.

Yet you see people like the economist in Forbes magazine and you wonder, was he born from a machine?

Libraries and community centers offer a myriad of services of that help humans to become better socially and culturally. The sole fact that they provide you with the opportunity to educate your self for free is a wonder that most privileged people fail to see. And this difference alone can change your life from a certain failure to a possible success.

Hello, congratulations on the podcast! I like the the topics, the way they are approached and how at the end it always feels like listening a really good story. I was initially drawn to this specific episode because of the picture. This is the public library of my hometown’s public university: Universidad Michoacana de San Nicolás de Hidalgo in Morelia, Michoacán, México. I saw that in most of the pictures showing buildings, the names of the places are written at the bottom of the picture. So I wanted to add the information for this one as it really is a beautiful library and it was a nice surprise to see its picture.

My kid plays D&D at the library with friends after school! Long live libraries ❤️

I love this discussion and I love libraries! They are also more environmentally friendly than all of us buying all those materials.

What I really want to comment on or ask is about the broken window theory. You asked what should have been an obvious question: “why not fix the windows?” But I want to go back even one more step and ask why is there abandoned property in the first place?

I live in the Toronto suburbs, and abandoned property is rare. Other than old farm houses, I think abandoned properties are rare across Canada. (Relative to what I see in the US).

I’m guessing there must be legislation (property tax laws, liability???) that makes it more undesirable to abandon property here.

This was a truly excellent episode; the guest was excellent, the topic is very germane to our current situation, and Roman asked some really good questions–all around excellent. I’d have liked to hear more about the design characteristics or considerations for social infrastructure. I suspect there’d be some overlap with prescriptions from both Ostrom and Olmsted.

Also, congratulations, Avery! A great series from a great producer. I really enjoy your work.

I live in Seattle and while I listened to this episode I thought of how in 1998 voters in Seattle passed the “Libraries for All” bond, which not only built the amazing central library, but rebuilt many of the branch libraries. Now 20 plus years later, Seattle has this amazing library infrastructure. I use the library often and when I go it is packed at all hours that it is open.

Loved this episode!

Broken Windows Theory actually recommends the very methods taken by the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society as well as more proactive policing. As this article explains, “people perceive the broken windows as a sign that no one is organizing the neighborhood — meaning those intending to commit crimes would feel like they could get away with it there.” So the broad solution is to organise the neighbourhood in a visible way. Denying drug dealers and squatters space by boarding up abandoned buildings and maintaining lawns are laudable but only go so far. There are many areas where the situations during which crime is more likely occur on the street itself. Hence, police patrolling and taking away illegal weapons and drug paraphernalia (stop and frisk) are vital parts of organising a neighborhood.

Hey 99pi team, thanks for the great show!

Related to this story you should really check out the new public library of the Aarhus, Denmark.

Its called Dokk1 and its built around the idea of a noisy library. No shhhing librarians here.

Look here: https://dokk1.dk/

Some (me) might find it ugly as can be on the outside. A big grey steal and concrete UFO has landed in the middle of the city, but with that said, it works amazingly well on the inside.

Yeah its a library. But its also a cafe, a light rail station, a 1000 car underwater, robot controlled parking space, an art center, a makerspace, a ad hoc nursing school, the local civic center, playground and commercial office space. It features a 4 meter tall bell to ring out every time a new citizen is born into the city and handcrafted giant eagle, bear, vulcano and dragon around a massive hovering balcony running around the whole building. And the fact that there is not a single wall anywhere between three stories. Its just one big spiralling ramp through the whole bulding. It even has a level 2.2 because why not…

It has truly become so much more than we ever thought a public library could be.

A loud, social center of the smallest big city in the world.

I love 99PI soooo much, and I absolutely loved this episode.

But why is the first thing on this blog post a link to purchase the book on amazon.com!?

Wouldn’t it make more sense to link to the book’s bibliographic record? (Which, by the way, shown on worldcat, will allow people to see nearby libraries that own it!)

http://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1130791723

As a Librarian myself, I know that’s what I would do!

Btw — I know this post is over a year out, but NY Times linked me here in introducing Klinenberg’s recent Op-Ed!!