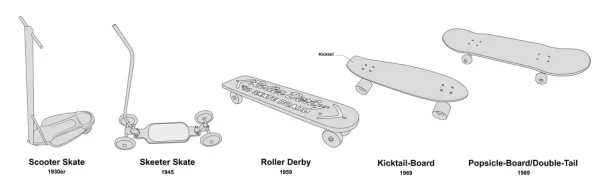

Watch a skate video today, and you’ll notice how similarly shaped the boards are. It’s called the “popsicle” design, because the deck is narrow in the middle and rounded off at both ends, like a popsicle stick. This may seem stupid simple, but that basic, clean popsicle shape is actually the product of a lot of experimentation and iteration. In 1989, one particular board would cement skateboard design as we know it. But to understand it, we have to go back over a decade to the mid-70s, as more and more money poured into the growing sport.

Compared to the skating that you see today, 70s skatepark action was relatively gentle — parks like rolling hills crafted from concrete. And kids wore pads and helmets, because: safety first. It was kind of like roller skating — it was supposed to be for everybody. But the sport hit an apex and seemed to be in permanent decline, like hula hooping, pogo sticking, or any other craze of that era. Kids grew up and moved on.

That was the end of this first wave of skateboarding, and an end to the notion that it would be this mass, widespread, mainstream sport. But while it died as a trend it didn’t die out entirely. The people who stuck around didn’t do it to be cool or get rich. They stayed out of love. But with skate parks shutting down, they had to evolve new DIY designs, and start utilizing the built environments around them in new ways.

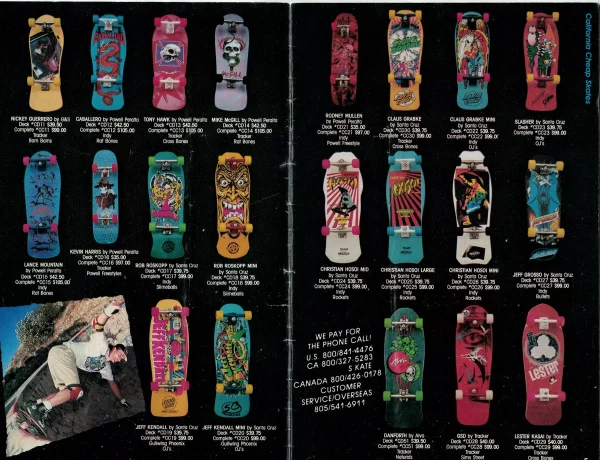

Suddenly, skaters weren’t on gentle, carefully crafted rolling hills, but big ramps, where they did big stunts. It was all about air. Skateboards had gotten bigger to accommodate this change — longer and wider, with a kick tail at the back of the board. Still, there was a lot of variation in where things bulged, curved, or tapered. There was this idea that the pros used custom-designed boards, optimized for them or their style of skating, which of course skaters then wanted to have, too.

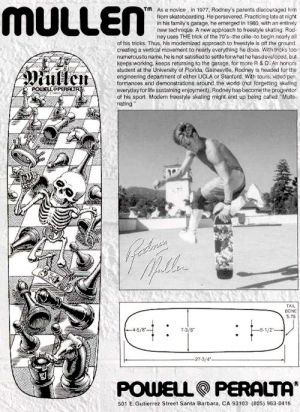

At the same time, skating continued to evolve on the streets of cities. Kids started to realize: not only do I not need a skate park, I don’t need a half pipe or a home built ramp or an empty swimming pool or anything. I can just go find a curb or a wheelchair ramp or an embankment behind a school, and I can just go nuts and come up with some cool tricks just using my city. This was the beginning of what came to be known as street skating. But the sport was still mostly two-dimensional, until a pro skateboarder named Rodney Mullen figured out how to do an Ollie on the flat ground., suddenly giving skaters access to rails, bleachers, stairs, a whole new multi-level playing field.

So the skating pendulum had swung from giant tricks back to more grounded, but still aerial, maneuvers — which meant the board didn’t need to be as big but they did need great tails for snapping and lifting. And because the street tricks were getting more sophisticated and technical, with all the spinning and the flipping, the board shape needed to be way less fussy and cumbersome, and more streamlined and smooth. The skateboard was evolving fast from a big, clunky piece of self-expression to this elegant tool. And so in the late 80s, it all culminates in a single skateboard model that arrives and becomes the template for the skate decks we know today.

And this latest, great innovation traces back to a skater on the East Coast named Mike Vallely. He had other skaters around him who were pushing him to try new things. At the time, he skated for a company called World Industries, which was run by some very young skaters. World Industries was aggressive at taking on all the dinosaur companies like Powell Peralta and Santa Cruz. And they did it by poaching their star skaters, and taking shots at them in their ads, which were gritty and edgy, appealing to the target demographic: skaters!

At the time, most skaters could only ride with one foot forward, their left or their right — directional skating. “Switch stance” skateboarding was rare, like being ambidextrous at writing, and it opened up a whole big bag of additional tricks. The head of World Industries, Rodney Mullen, saw this as a way to break new ground, and make more money. Between his vision and Mike’s fame, they started getting attention for a new kind of board: The Barnyard. This new board had two tails — and the beginning of something new: the double-kick skateboard. Between this cutting edge design and its wild graphics, the board was impossible to ignore, and influenced design for decades to come.

At the time, most skaters could only ride with one foot forward, their left or their right — directional skating. “Switch stance” skateboarding was rare, like being ambidextrous at writing, and it opened up a whole big bag of additional tricks. The head of World Industries, Rodney Mullen, saw this as a way to break new ground, and make more money. Between his vision and Mike’s fame, they started getting attention for a new kind of board: The Barnyard. This new board had two tails — and the beginning of something new: the double-kick skateboard. Between this cutting edge design and its wild graphics, the board was impossible to ignore, and influenced design for decades to come.

The Barnyard also supercharged a shift in the athleticism of the sport. Most skateboarders had learned to do tricks like the ollie with only their left or their right foot in the back. Now, with two tails, maybe you could learn with both feet. Forwards and backwards kind of become meaningless with a skateboard like this. And the wild success and flexibility of the board started to streamline the options for future board designs — suddenly, there was a “right way” to make a skateboard, with this as the prototype. That isn’t to say innovation is no longer possible, but it might take a paradigm shift — like parabolic skis, or the introduction of snowboards — to break new design ground.

The Barnyard also supercharged a shift in the athleticism of the sport. Most skateboarders had learned to do tricks like the ollie with only their left or their right foot in the back. Now, with two tails, maybe you could learn with both feet. Forwards and backwards kind of become meaningless with a skateboard like this. And the wild success and flexibility of the board started to streamline the options for future board designs — suddenly, there was a “right way” to make a skateboard, with this as the prototype. That isn’t to say innovation is no longer possible, but it might take a paradigm shift — like parabolic skis, or the introduction of snowboards — to break new design ground.

Leave a Comment

Share