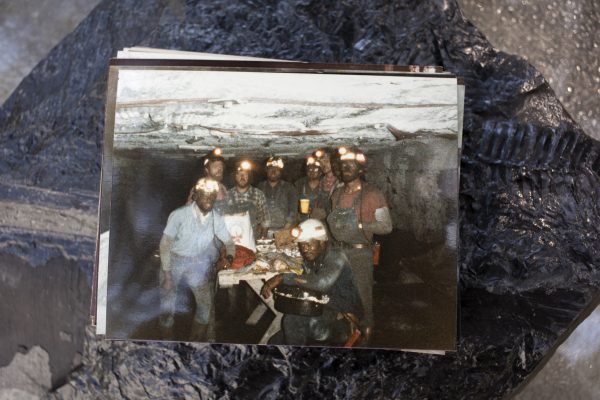

Ronnie Johnson still remembers the first time he went underground. He and a handful of other coal miners piled into a little trailer and descended into the mine. When they got down to the bottom, Ronnie’s boss handed him a wrench and told him to open a nearby water line. But someone had forgotten to cut the water off. The resulting torrent caught Ronnie by surprise and knocked him into a wall.

As a new miner in a dangerous industry, Ronnie had to go through an intensive orientation process before this first trip underground. He sat through 40 hours of training and safety classes before going down into the mines. He was also issued a yellow hardhat that identified him as a rookie, and given his first reflective coal mining stickers. He put one on his new hardhat and saved one in a box, later putting it into an album.

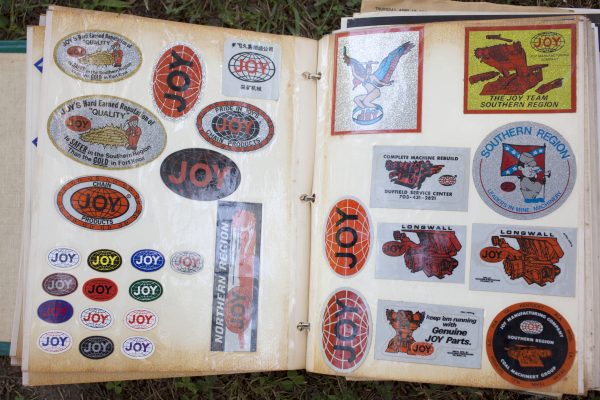

Today, after 34 years as a miner in Alabama, Ronnie has filled several photo albums with thousands of stickers. Some are inside jokes. Others commemorate big events or accomplishments at work. Some come from unions or manufacturers connected to the industry.

Lots of other coal miners across the country have collections like Ronnie’s. Miners use these stickers for safety and for communication, and as a kind of currency down in the mines. And for many miners, collecting them was a natural extension of their utility. “It was just what coal miners did,” says Ronnie, like how “kids collect baseball cards.”

Since the beginning of underground mining, one of the biggest dangers in the workplace has been the darkness, which can lead to accidents. Even though technology has improved to make mines brighter and safer over the years, it’s still an issue today. The culture of mining, to a certain degree, has been shaped by the level of risk involved.

Elaine Cullen, an occupational ethnographer who has spent a lot of time with miners, says that jobs “like mining, firefighting, police work, the military, deep sea fishing,” where people face dangers together, tend to develop very strong cultures. When she first went into a mine, she was told she needed something reflective on her hardhat for visibility. “We put strips of reflective tape on the back of our hardhats,” she recalls, but she saw a lot of miners with other reflective stickers.

The stickers started out as little advertisements that the manufacturers of mining equipment handed out. Even before the late 1960s, when mining safety laws started requiring reflective materials underground, miners used those stickers to stay visible to each other.

As time passed, the stickers evolved. They became more personal and started to tell miners’ stories. And the mine companies themselves started printing stickers for their workers. Stickers went from simple ads to signifying an identity. And as their role changed, stickers also came to serve as a kind of currency among miners. A trucker coming to unload supplies at a mine might start to learn that help is more forthcoming, for instance, if they have stickers to hand out to workers.

After a year in the Alabama mine, Ronnie swapped out his yellow hard hat for a black one, which meant he was no longer a rookie. With that came more stickers, which generally came in twos: one went to the hardhat and the other to his growing collection.

Managers at the mine gave him stickers with the mine’s name on them and his union gave him stickers with union messages on them. One of his favorite stickers has the state of Alabama outlined in red, with the text: Alabama Coal Miner. “That’s kind of a pride thing,” he says.

As he gained more experience, he got stickers commemorating his accomplishments. He worked at a company early on that counted the amount of coal mined by the number of cars filled during a shift. He has stickers for 100 cars, 150 cars and even 225 cars in a single shift.

In the 1960s and 70s, there was a national movement for mine safety — new laws were passed and agencies established to address industry dangers. As part of this push, Elaine Cullen was hired by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, a federal agency, to develop a safety training program for coal miners. She knew she might be facing some skepticism from the miners she was trying to reach. “I don’t look like a miner,” she says. “I’m a woman and most of them are not. So getting them to work with me, especially when I was a representative of the federal government,” was difficult at times.

Elaine had seen that the miners were really into these stickers, and she figured she could use them to gain their trust while also helping convey safety messages. But she knew just putting “work safe” on a sticker wouldn’t cut it. She needed something to grab a miner’s attention.

Working in Kentucky, Elaine learned that some miners called each other “coal hogs,” referencing their enthusiasm for and skill at the job. So she took that idea and designed a sticker with a big muscular pig with a hard hat on that says “coal hogs work safe.” Miners loved it.

Some of Elaine’s other designs were duds. Her team made one with a dead canary (canaries were once used to check for bad air in a mine). But that was a long time ago and the younger miners didn’t get it.

Other stickers catering to raunchy mine humor didn’t pass muster with her bosses in the federal government. For example: Elaine’s team designed one sticker to remind miners to check for gas in mines. It showed the “back end of a donkey,” she explains, with the donkey looking backward. It read: “don’t be an ass, check for gas,” with a cloud coming out. Gas can be really dangerous underground, and Donkeys were once used to carry coal out of the mines. Higher-ups in her agency were not big fans, but miners loved it.

Mining stickers aren’t something you can easily buy in a store. Unless Elaine visited a particular mine, her stickers would be hard to come by. A lot of stickers are specialized and location-specific—depending on what organization or company designed them, how many were printed and where they were distributed.

Hardcore collectors, though, can build up tens of thousands over a career, in part by going to sticker swaps and exchanging across collections. Lennie Haller, a coal miner from Illinois, has over 26,000 stickers in dozens of albums organized by type: stickers from manufacturers in one album, unions in another, and so forth. Like photo albums, these can serve to remind miners of milestones and stories. “They are just little pieces of our history, of our past, little mementos I guess,” says Lennie, “like a postcard.”

Of course, just like with photos, some of the darker memories don’t end up in the album. In 2011, after more than 30 years in the mines, Ronnie, had an accident. His hand got pulled into a machine and it took a finger. He was rushed to a hospital and was told to call his wife. “I remember Debra looking at me when she came in,” he recalls, and marveling at how dirty he was. He had never shared much about his life in the mine with his family. “I guess she never saw me like that,” he muses. “I didn’t tell them what I went through.”

Ronnie says before he lost his finger, he’d gone 31 years without spending a night in the hospital. He’d never ridden in an ambulance, never had an accident in the mine that made him lose work hours. Then, it all changed in a day. Ronnie never got a sticker for that.

Comments (6)

Share

Great episode! Underground spaces also house neutrino detectors. One of my favorites is ‘Super-K’ in Japan. The images of thousands of fragile detectors are awesome.

Fun fact, It’s against safety standards to put stickers on hard hats because if it cracks the stickers can cover those defects. Its a common practice on construction sites as well.

As cool as the stickers are, I’d love to see the pictures/videos of these abandoned/unabandoned mines you talked about at the end. Not seeing them on the 99PI homepage though.

Agree!

Found it! The story about reimagining abandoned mines is over here.

Great episode! I lived in Pittsburg, CA (not too far from Oakland), and I was hiking near my place and came across an old silica mine and an old coal mine. They give tours (I think it was about $5), and provide an interesting glimpse into the mining industry in the Bay Area. Here is a great article with contact information for anyone interested:

http://www.mercurynews.com/2015/03/03/mine-tours-are-open-again-at-antiochs-black-diamond-preserve/