On October 17th, 1989, the Oakland A’s were playing the San Francisco Giants in the World Series, but just as the game was kicking off—the television broadcast cut out. When the signal came back, it was no longer the baseball game. These were the early minutes of the Loma Prieta earthquake, which struck near Santa Cruz. It was the first major earthquake ever to be broadcast live on national TV.

Part of the Bay Bridge had been destroyed. There were fires, fallen buildings, and widespread power outages. In all, there were 63 deaths and almost 4,000 injuries. But this is a story about what happened to the San Francisco Public Library after this earthquake. It suffered a lot of damage.

No one was injured at the San Francisco library. But the earthquake had dumped half a million books on the floor. Even after two months of repairs, the post-earthquake situation in the San Francisco Public Library was still pretty bad. A large portion of the stacks had glass floors, and some of these had cracked.

Library management designated a new room for public browsing. Librarians curated a selection of books they thought the public would most like to read, and those books went in that room, “But they realized along the way that not every book was going to fit,” says Jason Gibbs, Manager in the Art, Music & Recreation Center at San Francisco Public Library.

But even this winnowed down selection of books was too large for the available space. They needed to winnow it down even more. “The earthquake just happened, and we don’t have this shelving anymore. We need to make space,” Gibbs says. “That’s a reasonable thing to do if you approach it in a thoughtful way.”

Weeding

Libraries get rid of books all the time. There are so many new books coming in every day and only a finite amount of library space. The practice of freeing up library space is called weeding. “It’s like, you have to weed your garden for […] the flowers to grow,” says Sharon McKellar who supervises Teen Services at the Oakland Public Library.

There are specific guidelines that come along with book weeding. McKellar, and many other librarians, at libraries all over the world, weed their shelves using the same set of guidelines. And it has an excellent acronym: MUSTY.

M — for Misleading, or factually inaccurate.

U — for Ugly

S — for Superseded by a new edition or a much better book.

T — for Trivial and

Y for Your-collection-has-no-use-for-this-book. Because they want this acronym to work.

The T and the Y are the tricky ones. They’re not necessarily statements of fact; they’re judgments of value. What’s trivial to me might be very important to you, and vice versa. Even here, these judgment calls are made by librarians who specialize in the relevant section, and based on circulation statistics. You just have to trust that your librarians are doing their best for the public.

“We want to be able to keep bringing you the most relevant, most current information, and the only way to do that is by having room to do it. So the only way we can do that is by sometimes withdrawing the things that are not as useful anymore,” explains McKellar.

For the sections that do have to get weeded, weeding is generally a touchy subject. The reason why is probably already clear to you: people don’t like the idea of books being thrown away. We love books. And no one loves books more than librarians. It can be hard for them too.

Weeding is normal and necessary, but the big problem was that after the earthquake, the San Francisco Public Library started getting rid of an unusual number of books. The librarians were told to move quickly. And they didn’t use MUSTY. Or any sort of comparable system.

GREEN. YELLOW. RED.

After the earthquake, the librarians were ordered to go through each collection book by book, and insert a slip of paper into each. There were three colors of paper: green, yellow, and red. Green meant the book had been checked out that year. Yellow meant the book had been checked out in the last two years. And red meant that it had been over two years since somebody had checked out that book. The red books were the ones that were in potential danger of being tossed.

Compared to the careful consideration of MUSTY, the system of the green, yellow, and red cards was a rather blunt instrument. Also, it wasn’t really clear where the red card books were going to go, or if they would ever be used again. In Jason Gibbs’s department, for example, the Art & Music Collection, the discarded books got sent to an abandoned hospital owned by the city because there was nowhere else to put them.

Even battle-hardened librarians like Gibbs felt that the weeding was happening too fast, and too carelessly. You had librarians in different sections weeding furiously and not really communicating with each other. As a consequence, lots and lots of books were leaving the library. And no one quite knew how many, or exactly why.

The Electronic Library

In the late 80s, well before the earthquake struck, the San Francisco Public Library was starting to reconceive of its mission in light of a new technology: the internet. A big part of this pivot was when, in 1987, San Francisco hired Kenneth Dowlin as its new City Librarian. He had recently published a book called The Electronic Library, in which he argued that technology was changing the way people found information and therefore changing the role of librarians.

Dowlin certainly understood, as early as 1984, what the Internet was going to do for communication. Some, however, felt that Dowlin had a distressing lack of concern for books. “There was this sense that, when it came to the physical collections, he just didn’t have any interest,” says Librarian Jason Gibbs.

As a part of his vision for the library of the future, Dowlin was also overseeing the design of a new Main Library for the city of San Francisco. It would be a $100 million structure with more than just bookshelves. It would be wired for computers and television.

This new main library would have twice as much space as the old one, but much of the library’s interior would be devoted to an eighty-six foot tall atrium in the middle of the building, which would rise to a conical glass roof. Lots of librarians felt this big empty atrium was just a step too far. They worried it wouldn’t leave enough space for books.

The Guerilla Librarians

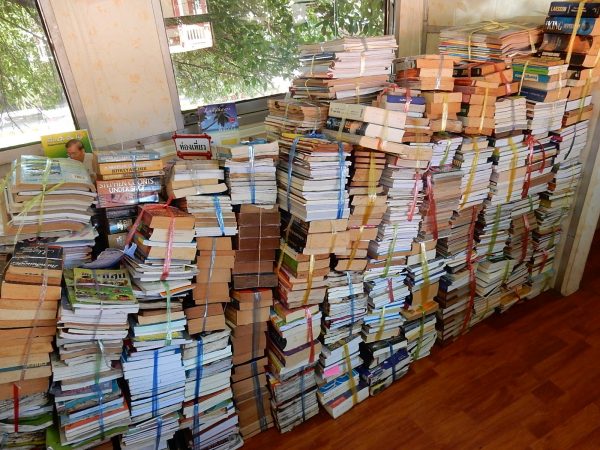

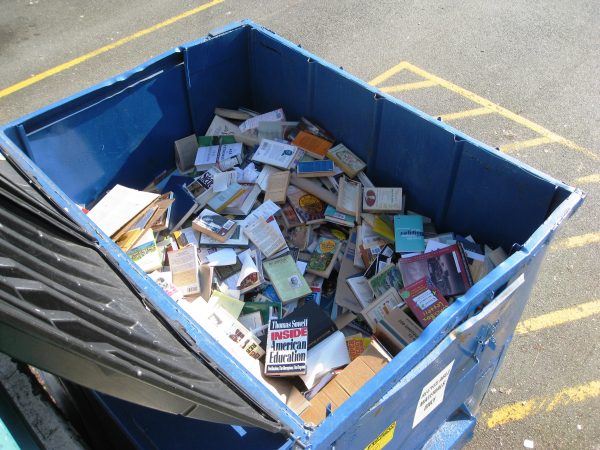

The earthquake was a perfect excuse for Ken Dowlin to do what he wanted to do anyway: shrink the physical collection before the move to the new library. Dowlin’s administration started sending books to landfills. In the days after the quake, books were being sent out by the truckload. Several times a week. This is not normal library practice.

Twenty-seven librarians signed a petition asking Kenneth Dowlin for the weeding to stop, but that didn’t work. Jason Gibbs and his colleagues decided to do something. Librarians from several departments banded together and called themselves the “guerilla librarians.”

Guerilla librarians snuck into the shelves and replaced red slips with green ones, thereby designating the book as a circulating book and keeping it in the collection. The guerilla librarians wanted to determine exactly how many books had been weeded and discarded, but nobody knew for certain. And there was a risk that they’d never be able to find out. Because Kenneth Dowlin decided to get rid of the physical card catalog.

Dowlin’s logic for getting rid of the phsyical card catalog was pretty sound. They had already stopped updating the catalog in 1991, and at that point, more than 90% of the nation’s libraries had computerized their card catalogs. The earthquake had actually allowed the San Francisco Public Library to modernize their database– with the disaster relief money they were granted, the library was able to get electronic catalog software.

The move to get rid of the old card catalog caused a surprisingly intense outcry from the guerilla librarians. Not because of nostalgia or personal preference. It was because if a book had been weeded and discarded, it wouldn’t be registered in the new digital system and there would be no evidence it had ever existed at all.

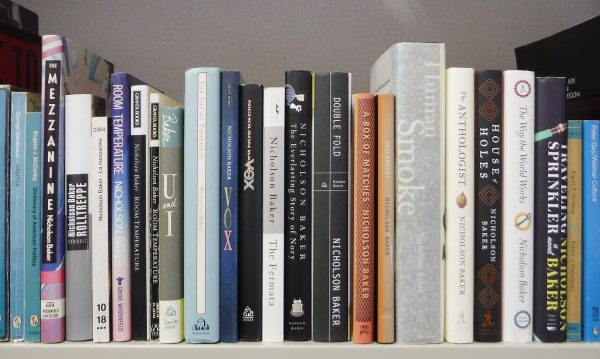

In order to get to the card catalog, the librarians pulled out their secret weapon: Nicholson Baker, writer and library activist. In 1994 Baker had gotten national attention for a New Yorker article about the disposal of physical card catalogs, a practice that had become increasingly common, and had upset Baker a lot.

In 1996 the guerilla librarians reached out to Baker for help. The lost books, evidenced only by their locked-away card catalog, were teetering on the edge of disregard. In their email to Nicholson Baker, the guerrilla librarians wrote, “You are the only one who can save it now.”

Baker made a formal request to inspect the card catalog, but Kenneth Dowlin denied it. So Baker sued the library for access to the card catalog. This lawsuit took a while, and it was a bit of a mess, but it automatically classified the card catalog as a public document. Now the library had to keep it.

The guerilla librarians snuck into off-limits areas in the library, and the abandoned hospital building where the books were stored. They took away books that were going to be destroyed and stockpiled them by the hundreds in their homes, in their cars, in their offices, in lockers, in boxes — all in the hope that they would someday be returned to the library.

The Author vs. the Library

In April of 1996, the New Main Library opened its doors, to much fanfare. Only a month later, in May of 1996, the guerrilla librarians organized an event of their own. There, in the library auditorium, Nicholson Baker delivered a speech stating what he had found.

Baker contended that Dowlin was responsible for a massive destruction of books, the “systematic removal to a landfill” of at least two hundred thousand volumes. The phrase that got Baker the most attention was when he called this mass disposal “a hate crime directed at the past.”

The library hit back, condemning Baker for accusing them of a hate crime, and then both sides started lobbing insults at each other, as local and national press piled on. One paper compared Baker to the Unabomber. Things got a little out of hand. The library hit back, condemning Baker for accusing them of a hate crime, and saying that he had misunderstood the problem. The library also tried to discredit Baker because of some bad math he had reported. It turns out, one of the guerilla librarians had messed up the measurements of the old library shelves: in fact, the new library had much more space for books than the old one.

In the midst of this feuding, the new library had already been built. And three times as many people were streaming through its doors. Judging from the influx of visitors, it was a success.

Some of the books saved by the guerilla librarians in boxes and lockers were transferred back into the collection. But at the end of the day, the controversy wasn’t only about what to do with old books. It was a debate about what books are. Are they beautiful objects that we can smell and touch and collect? Or are they eternal sources of knowledge, accessible to everyone in the ether?

Cast Your Vote

Nicholson Baker can see Dowlin’s perspective, and appreciates being able to conduct research seamlessly over the internet. But Baker maintains that we shouldn’t give up on the printed page. His argument, and the public battle around it in the nineties, was a big reason why the San Francisco Public Library totally overhauled their collections policies. They made it a policy that if a library branch is considering weeding the last copy of a book, they must send that copy to a subject specialist, who will decide if it can be weeded or not. For the books that do have to go, the San Francisco Public Library developed a community redistribution program, to make sure the extra copies of popular books can live on somewhere else. Weeded books from the SFPL are sent to schools in the area, city colleges, and prisons.

One of the biggest changes to the modern practice of weeding is something that Kenneth Dowlin himself helped establish: online communication between libraries. Jason Gibbs, at the SFPL, and Sharon McKellar, across the bay at the Oakland Public Library, can now communicate with each other instantly over the internet so they can make different volumes available to readers in both cities. It’s a way of sharing shelf space. Some libraries spell “MUSTIE” with an I and an E at the end (instead of a Y). For misleading, ugly, superseded, trivial, irrelevant, or elsewhere.

“For me, weeding is fun,” says McKellar, “It’s a chance to really touch the books and see how they’re doing and see what people are interested in.” That’s what this all comes down to: it’s what people are interested in.

Weeding isn’t just about what to cut. It’s also about what to keep. It’s about what the public wants to read. And so every time you check out a book from the library, you are casting a vote, to your local librarian out there in the weeds, to keep this title in circulation.

Comments (10)

Share

ZOMG. I wish you’d talked to a few other librarians about the weeding process. A public library collection is a living thing. It must shed some percentage of items continually to allow new growth. Public libraries are usually not set up to be historical archives. They are meant to lend popular materials.

Many, many books are not tomes meant for the ages. Books wear out physically too. While that fight at SFPL was raging, the books that were hoarded by the guerilla librarians were slowly losing their value. Only a fraction of the fiction would even still be desired by the public and many, if not most, of the non-fiction would have been superceded by new titles. I don’t advocate throwing out books wholesale but non-librarians often fetishize a physical book to the point of absurdity. Who wants to borrow a ratty paperback with food stains? Or an outdated novel from 25 years ago?

And as far as that physical card catalog is concerned, the furniture itself is now highly desirable by many folks (check the prices on eBay or any antique store) but I don’t know any library worker who actually wants to go back to using those as a catalog.

But the Kentucky Packhorse Librarians story is near and dear to my heart, being a librarian in Kentucky myself. There were packhorse nurses in Kentucky as well and both groups did tremendous work in a very inaccessible landscape. Thanks for sharing! Big fan of the show!

I’m sorry, but your comment is chock full of a lot of insults. You’re assuming the books “hoarded” by the guerilla librarians were fiction. And how much value do books lose rotting in a landfill?

As for the card catalog, how did you miss the point of access to it was to learn how many books were lost in the wholesale dumping in the early days? Wanting to know what was lost and an accurate idea of what you have is not absurd.

I have an appreciation for digital books because reading is my passion. And my limiter isn’t money or time, but physical space. With my Kindle, I read somewhere between 400-500 books a year. But I still have all of my favorites from early childhood, school years, and into adulthood. Over time, due to that space limiter, I’ve had to weed my own physical collection before I received my first Kindle and started buying digital books.

However, I go back and handle and re-read those books—yes even the early childhood ones—because they mean something to me or I simply loved the story. The time, emotion, and memories an author put into the story, the artwork, and my own memories associated it with it: who gave it to me, where did I buy it, when did I first read it, events that happened when I was reading it.

That’s not me “fetishizing” a physical book, but appreciating everything about it. I would hope librarians have that same appreciation for books. And I would hope if one individual initiates wholesale destruction of a library’s collection, other guerilla librarians would step up to help protect their collection until appropriate steps can be taken before it is lost forever.

This episode brought back a lot of memories for me. As a high school student I worked at my local library in rural Manitoba, Canada. While working there I saw how the head librarian was changing the nature of the library, getting rid of general adult fiction and nonfiction to make room for an ever-increasing number of Harlequin romance novels. The MUSTY guideline was not being followed. Instead the librarian would weed the stacks by determining when the book was last checked out, as per the most recent date stamp on the back of the book. I was upset to be seeing classics and books that, though not checked out often, I felt needed to be part of a well rounded library, were being discarded. So, in my rebellion, I would take time on my shifts to go through the shelves with my date stamp and secretly put an updated due date on titles I felt deserved to stay. Next time the librarian would weed the stacks she would look at these recent due date stamps and therefore not weed out the title. I am still pleased with myself!

How wonderful that you, a high school student working part time at your local library, knew better than a full time, accredited librarian who ostensibly had the education and experience to be in charge! I’m sure you knew so much better than she did about what sorts of things patrons were actually requesting to read, what the circulation statistics looked like, what the turnover rates for various collections were, what the item replacement policy was, what the circulation goals and standards were, and what the materials budget allowed for. How very valuable your insight must have been!

I hear this a lot: “The librarian was changing things…”

No. User behavior is changing, so the librarian is making changes to support the users.

A great episode. College and university libraries are also engaged in a battle of the books, as some want to reinvent libraries as “spaces” in which books are not the priority.

The SF story reminded me of a nearby story of weeding gone wrong, at the Urbana Library, Urbana, Illinois. There, every book published more than ten years earlier was to be removed — truly what Nicholson Baker would call a hate crime against history. This story ended with the library director’s departure:

http://www.smilepolitely.com/culture/do_you_ever_read_any_of_the_books_you_weed/

http://www.smilepolitely.com/culture/miscommunication_or_mismanagement/

http://www.news-gazette.com/news/local/2013-07-09/updated-urbana-library-seek-early-separation-director.html

A great episode. College and university libraries are also engaged in a battle of the books, as some want to reinvent libraries as “spaces” in which books are not the priority.

The SF story reminded me of a nearby story of weeding gone wrong, at the Urbana Library, Urbana, Illinois. There, every book published more than ten years earlier was to be removed — truly what Nicholson Baker would call a hate crime against history. This story ended with the library director’s departure.

It seems that your comment form doesn’t allow for links, but searching for urbana free library and weed will turn up relevant reports from Smile Politely.

A few years ago, some friends of mine decided to find the library books that had had the longest gap between being checked out. The library claimed they could not tell this from the electronic catalog, however do to the age of this library, they previously used physically stamped checkout cards that were glued into the books. Through these cards, we were able to find books that hadn’t been checked out in 75, 90, and 103 years.

We were so excited, look at this history we were finding within the stacks, but then we stopped. We couldn’t check these books out to read them. That would destroy their uniqueness. And we couldn’t tell the librarians or they might decide to weed out these books.

Library collections are unique to their location, and that is part of the beauty of library collections.

I am a librarian, and one major issue that was not discussed in the electronic vs paper portion is one of equity. A paper book can be checked out and used by anyone who can read. An electronic resource often requires equipment to use and sometimes an active Internet connection. There are ways to help get around this, but for the most part accessing electronic resources effectively if you do not have a computer/tablet/e-reader involves being physically at the library or another location that offers the tools to access.

Yes, the current push to subsidize smartphones for low income people helps some, but it is not an effective way to read more involved work.

For those outside the profession libraries are generally grouped into basic types: public, academic, school, archive and specialty. Public libraries (and school libraries) generally look at the interests of the patrons when considering collection development (both acquisitions and weeding), but there are some things that are usually kept because they are important, or some collections that are more towards archive – a common example would be a local history collection. It may not circulate much, but the library keeps it around.

The role of libraries in our society needs to change and adapt in the digital age. The Oakland Public Library has done just that with their creation of the tool lending library. I wish other libraries would follow suit. This library gives the DIYer not just the knowledge of how to fix things from the traditional library but now the tools to make it happen.