We meet Andrew Leland as he’s suspended in the liminal state of the soon-to-be blind: he’s midway through his life with retinitis pigmentosa, a condition that ushers those who live with it from sightedness to blindness over years, even decades. He grew up with full vision, but starting in his teenage years, his sight began to degrade from the outside in, such that he now sees the world as if through a narrow tube. Soon—but without knowing exactly when—he will likely have no vision left.

Full of apprehension but also dogged curiosity, Leland embarks on a sweeping exploration of the state of being that awaits him: not only the physical experience of blindness but also its language, politics, and customs. He negotiates his changing relationships with his wife and son, and with his own sense of self, as he moves from his mainstream, “typical” life to one with a disability. Part memoir, part historical and cultural investigation, The Country of the Blind represents Leland’s determination not to merely survive this transition but to grow from it—to seek out and revel in that which makes blindness enlightening.

Thought-provoking and brimming with warmth and humor, The Country of the Blind is a deeply personal and intellectually exhilarating tour of a way of being that most of us have never paused to consider—and from which we have much to learn. Get your copy of the book here.

The Country of the Blind

Reporter Andrew Leland has always loved to read. An early love of books in childhood eventually led to a job in publishing with McSweeney’s, where Andrew edited essays and interviews, laid out articles, and was trained to take as much care with the look and feel of the words as he did with the expression of the ideas in the text. But as much as Andrew loves print, he has a condition that will eventually change his relationship to it pretty radically. He’s going blind. And this fact has made him deeply curious about how blind people experience literature. As part of his research for this story, Andrew attended the Touch This Page! exhibit and symposium where he learned about the history and multisensory experiences of blind reading. The work of both the exhibit and symposium was essential to putting together this episode.

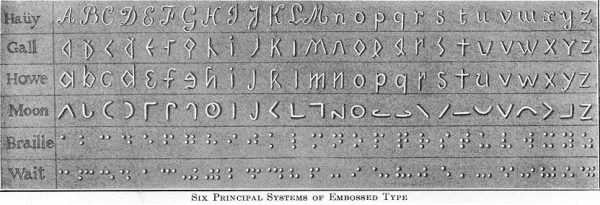

Traditionally, books are visual objects. And for centuries now, blind and sighted designers have been arguing over the most effective way to translate the visual, ink-print book into an accessible form for people without sight. For as long as blind people have been reading, there’s been this tension between systems that try to stay close to the original form of a book, and systems that radically depart from our ideas about what a book can be.

Sighted designers have made incredible breakthroughs to create non-visual forms of reading for blind readers. But, as one blind critic pointed out, sighted designers also have a bad habit of “talking to the fingers in the language of the eyes.” The history of blind reading is really the history of finding a new language for the fingers, and for the ears — one that captures the essential elements of the ink-print book, but in a new language that’s unbound from the visual.

And that history centers around two main shapes: lines and dots.

Before Braille

In 18th century Europe, before braille was invented, blind people weren’t even taught to read at all. Mike Hudson is the museum director at the American Printing House for the Blind, and he says that no one thought it was possible for blind kids to learn.

Without access to education, blind people were overwhelmingly poor, and their employment prospects were dim. If their families had enough money and time to support them, they usually lived at home, like adult children sitting idly around the house. Many others were forced to beg on the street. There was a handful of institutions in Europe to support the poorest cases, but they pitied the blind and hid them away from public view.

But then a man named Valentin Haüy came along. Haüy was born into a family of weavers in France, and he was a skilled linguist. He was first inspired to help the blind in 1771 when he saw a group of blind people being mocked during a street festival in Paris. They had been given dunce caps and giant fake glasses, and they were made to play musical instruments and to pretend to read books.

So Haüy founded the first-known school for the blind, The Royal Institute, in Paris. But even as he was getting the school going, Haüy kept a side job as a translator for the King of France and, every now and then, he’d receive fancy, embossed invitations for events. One day one of Haüy’s students touched one of these embossed invitations and felt the raised lettering. Haüy realized that raised lettering might allow blind people to read.

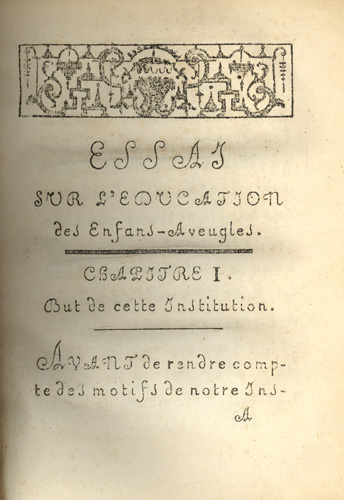

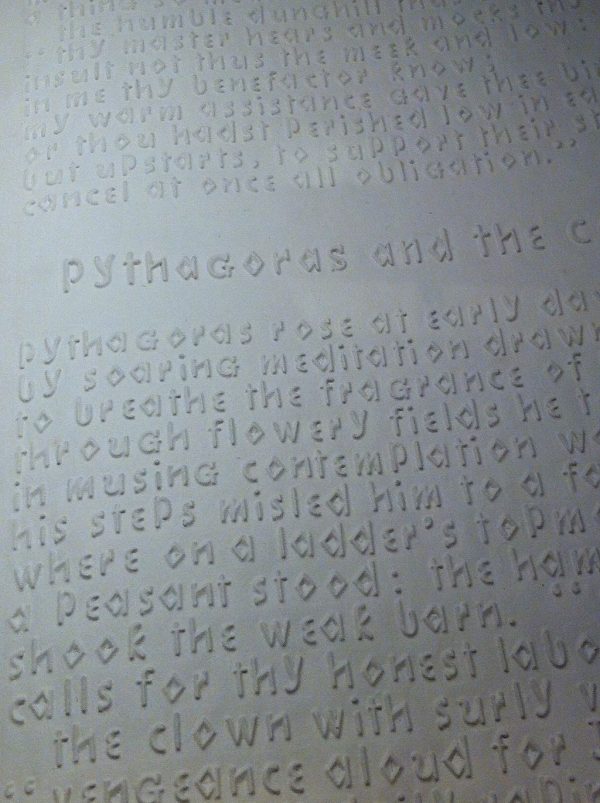

In 1786, Haüy printed the first machine-embossed book for the blind. It was a treatise on blind education. It’s written in print — the kind that sighted readers would recognize — but the text was all raised so that blind students could feel the shape of the letters. It was a radical move — not just the first book for blind readers in history, but the beginning of the idea that blind people can be systematically educated… But there were a few problems.

For one, the books were massive and prohibitively expensive. Also, they were just really hard to read. They were filled with ornate 18th-century letterforms, with their curlicues and flourishes, which were confusing under the fingertips.

It wasn’t until many years later, near the end of Haüy’s life in 1821, that another blind reading system began to develop.

It Bears the Stamp of Genius

It started when a captain from Napoleon’s army visited Haüy’s school to share a system that he’d developed for French soldiers. The system allowed his men to silently communicate with each other on the battlefields at night. He called it “nocturnal writing.”

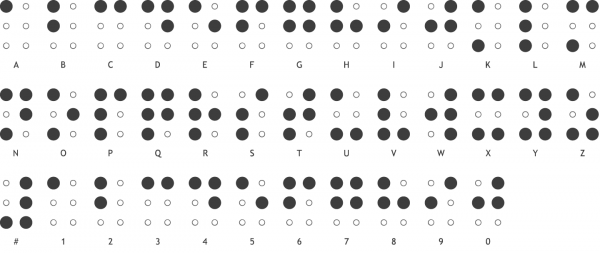

The director of the school at the time let a group of students experiment with the embossed pages that the captain had left behind. And in that group was a 12-year-old blind kid… named Louis Braille. Over the next few years, he began to adapt that military code for blind people, as an alternative to raised print. Louis Braille simplified the military code and maximized its efficiency. He substituted the twelve dot system developed by the captain for a six-dot system, which allowed blind readers to read faster by recognizing a letter with the touch of a single finger.

And while this code was inscrutable to sighted people, it was the system that blind people needed — designed by a blind person who understood intimately the needs of those reading by touch. Another advocate for the blind would say of braille: “It bears the stamp of genius, like the Roman alphabet itself.”

But despite its effectiveness, Braille didn’t catch on right away. It wouldn’t become the dominant system in France for another 30 years. And it would also be nearly a century before it became the standard for blind readers in the U.S.

Because it was effectively suppressed — by a well-intentioned, world-famous visionary of blind education.

Boston Line Type

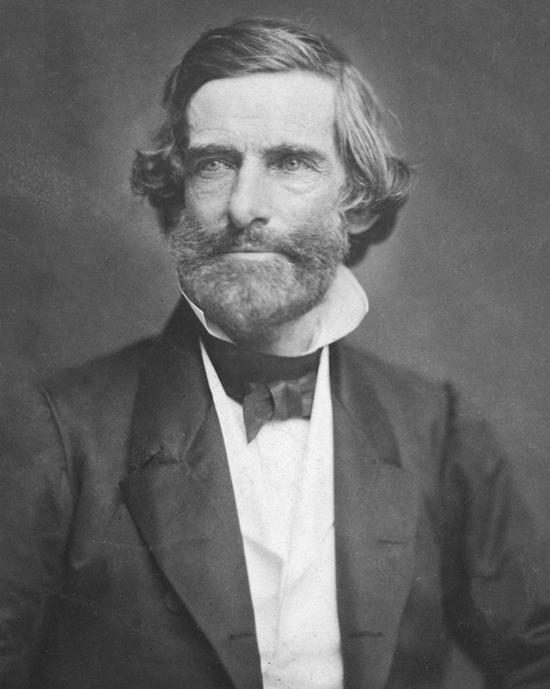

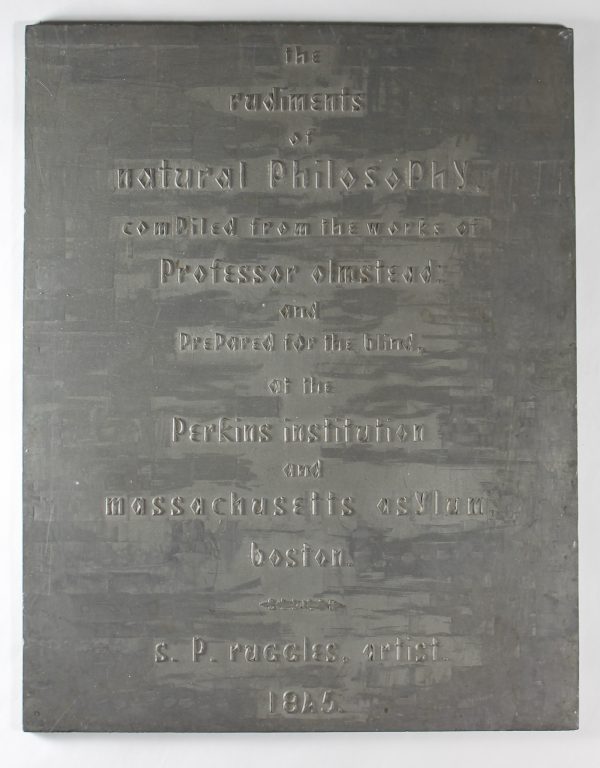

Around the same time that Louis Braille was quietly developing his new reading system, an American named Samuel Gridley Howe came to visit the Royal Institute in France. He was doing research in anticipation of opening the first school for the blind in the U.S. And while Howe, the American, was at the Institute, he saw the raised-letter books that they were printing. He was intrigued, but in true American fashion, he found all their fancy flourishes impractical. The American way, Howe thought, should be more economical, more sensible. So he decided to develop his own flavor of raised-print books, which he introduced at his new school, the Perkins School, in Boston. He called the system Boston Line Type.

“Boston line type is really the beginning of literacy as we know it as a movement for people who are blind in the United States,” says Kim Charleson, the Executive Director of the Perkins Library.

Boston Line Type stripped away all the fancy European embellishments of its predecessor, regularizing and streamlining the letters to make it more compact and easier to read.

Howe sharpened his letters’ curves into points to make them more distinct under the fingertips — the letter O, for example, is shaped like a diamond. Like the older French system, Boston Line Type could be read by both blind and sighted people. This is an obvious point if you’re able to see and you look at one of these books — the letters are easily legible. “Boston line type allows blind people and sighted people to sit down together and to read,” says Charleston, “There’s no barrier between them.”

This idea was really important to Howe. He didn’t want blind people to use a system — like braille — that was separate from what sighted people used. He thought it would isolate blind people and prevent them from integrating into the wider world. Long before the concept of “universal design” had been articulated, it was informing Howe’s thinking about how to design for people with disabilities.

But, as Mike Hudson explains it, raised letters are just not as good as braille. “Those letterforms are not unique enough from each other,” says Hudson, “sighted people look at braille and they go, ‘oh it all looks the same.’ But under the finger, those raised dots are just more tangible.” Not only that — you can write in braille. Unlike raised print, it doesn’t require a big heavy metal printing press. All you need is a small, simple tool — called a slate and stylus — that fits in your pocket.

The War of the Dots

By the 1860s, some schools for the blind in the U.S. had begun experimenting with braille. And while many faculty members still resisted it as an arbitrary, impenetrable system, the blind students who were exposed to braille argued passionately for its superiority to raised letters. At the Missouri School for the Blind, students passed each other notes and love letters in braille, knowing their teachers wouldn’t be able to read them if they got caught.

But Howe had invested a massive amount of time and resources into developing, distributing, and promoting Boston Line Type — and he’d become a hugely influential celebrity in the field of blind education. He was a master fundraiser, and key to that fundraising apparatus was the spectacle of a deaf-blind girl named Laura Bridgman, who Howe taught to read— using Boston Line Type.

Bridgman was the first deaf-blind person in history to get an education, more than a full generation before Helen Keller did. This achievement made Laura Bridgman — and Howe — international stars. Which Howe leveraged to make Boston Line Type one of the dominant print mediums for the blind across the U.S.

Like Howe, many of the directors and faculty at the schools for the blind were sighted. And many of them believed that they knew which system was best.

Catherine Kudlick directs the Paul K. Longmore Institute on Disability at San Francisco State, where she’s also a history professor. And she doesn’t even really buy Howe’s argument that Boston Line Type was “universal.” “He might have thought of it as universal, but it’s universal in that way that the colonizer thinks things are universal. It’s like you know these poor native peoples need educating and will try to bring them up to my level and make them like me.” Howe failed to pay attention to the expertise of the blind.

By the early 20th century, Howe had died. There were growing numbers of organizations dedicated to serving the blind, and more and more of them were being led by blind people. In 1921, leaders from the most influential of these groups gathered in Iowa to form The American Foundation for the Blind. The AFB quickly became the most powerful blindness advocacy organization in the U.S. And one of their first priorities was to make braille the dominant system.

But because it was still the wild west for braille in the U.S., the same thing happened that had happened with raised letters. Americans decided that they could design things better than those pretentious Europeans could. A whole cottage industry arose, with all sorts of competing raised-dot systems, commonly referred to as the War of the Dots. Before braille truly won out in the U.S., there was another 50 years of competing tactile systems.

The decisive battle in the War of the Dots finally came in 1909. Cities like New York were growing rapidly and, for the first time, they had enough blind children to start building day schools for the blind. There was a huge meeting of the New York Board of Education to determine which code they would use in New York City schools. In the end, braille won out. It was the beginning of the end for the competing codes.

By 1917, the rest of the country followed New York’s lead, and a newly standardized English braille became the main way that blind children were taught to read in the U.S. And with their increased self-determination and literacy, blind people were more able to integrate into society than ever before. Blind children were starting to be mainstreamed into public schools and some blind people began to get office jobs using tech like braille typewriters so they could work alongside sighted people, as equals. It’s what Howe had hoped Boston Line Type would help them do.

Talking Books

But for all braille’s advantages over raised print, it didn’t work for all blind people. Like the thousands of soldiers who were coming back from war with eye injuries who hadn’t learned braille as kids. Learning braille as an adult is really difficult.

As sound recording became easier and more affordable, those people who’d become blind later in life had new options that would transform our ideas about what a “book” can be. Translating ink-print books into sound might seem more straightforward than building a tactile reading system. After all, books were born out of a few thousand years of people telling each other stories, and we all learn to read by having books read to us. But early efforts to make recordings of books for blind readers brought with them a new set of design challenges.

The American Foundation for the Blind partnered with the Carnegie Corporation to publish experimental books on phonographic records. They called them “Talking Books.” They hired narrators, and pressed the recordings onto long-playing records, 25 minutes a side. These books were circulated by blind people about a decade before LPs became available to the wider public. The first audiobooks—and the first LPs—were made for blind readers.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xd6fOBw0i-k

But these Talking Books raised a big question: what should a book sound like? All kinds of organizations began trying to answer that question. The Cornell Ornithology Lab, for instance, took some of their bird song recordings and made a Talking Book out of them. When Snow White came out as an early animated talking movie, the AFB decided to make a Talking Book version.

But as Talking Books became more elaborate and theatrical — filled with sound effects and music — some blind people grew frustrated. As Mara Mills discovered in her research, more and more blind readers wound up breaking their record players trying to speed up the voices of the narrators. They weren’t listening for sonic aesthetic pleasure. They wanted the information, and the fancy productions moved too slowly for how fast they wanted to read.

Talking Books began to sound different. No-nonsense narrators like Alexander Scourby became more popular in the 1940s and 50s. Their voices became almost like fonts — standardized, legible, and most importantly, conveying information without getting in the way.

Finding a New Way to Read

In some ways, Andrew’s fears about losing his visual relationship to books resembles the anxieties that sighted people have about the demise of print in the digital age. As more and more people read on screens, there’s an old guard of folks bemoaning these new forms of reading as inferior. These critics believe that the trusty old technology of the book will always be the superior vehicle for ideas.

But the history of blindness and reading shows that the way we read has always been in flux. Many media scholars and book historians make the point that reading doesn’t happen in the eyes, or the ears, or the fingers. It happens in the brain. And that gives Andrew some comfort. But it doesn’t really soften the fact that blindness is, inescapably, a loss. No amount of historical research or conceptual reframing can hide the simple equation at work here: Andrew loves books — ink-print books — with marginalia and typefaces and dingbats. And going blind will take that away from him.

But he doesn’t want that to be his only conclusion, that blindness equals loss, full stop. He looks to someone named Harvey Lauer, as an example of a different way to approach his life as a blind reader. Lauer is a blind guy who worked at the V.A., testing all kinds of technology for the visually impaired.

One unique device Lauer used is called an optophone. It’s a kind of scanner that looks at text and then turns it into a series of tones representing the shapes of the letters. It’s another spin on universal design for blind readers: with an optophone, you wouldn’t need to create special books for the blind at all. With training, a blind person could read an ink print book using one of these devices.

Incredibly, some blind people actually learned how to read this way. After a lot of practice, they could hear these sounds and decode the words they represented, reading entire novels using what came to be called “musical print.”

Using devices he tested for the V.A., Lauer could read by vibration, through musical print, plus braille and super-sped-up talking books. He reads using more of his body, more of his senses than perhaps anyone else on the planet. His colleagues called him a cyborg — he walked around with devices dangling around his neck wherever he went, emitting vibrations and synthetic musical tones.

This sometimes led to funny incidents of confusion — like the time Harvey walked into a 7-Eleven and heard all these electronic tones coming out of the various machines in the store. He tried decoding them, because it seemed to him like they should be alphabetic. And then he realized they were just electronic tones coming from the cash register.

Harvey’s mistake in the 7-Eleven suggests to Andrew a way that his future as a blind reader might actually signal something other than a total loss… blindness could add something to his life, even as it takes something else away. Learning to read in new ways, through new senses, could increase his appreciation for the world around him.

Special thanks to Sari Altschuler and David Weimer. We found out about the story of Boston Line Type from their Touch This Page exhibit where you can see examples (and 3D printer files!) of Boston Line Type and other precursors to braille.

Leave a Comment

Share