In the late 1700s, a young man named Friedrich Froebel was on track to become an architect when a friend convinced him to pursue a path toward education instead. And in changing course, Froebel arguably ended up having more influence on the world of architecture and design than any single architect — all because Friedrich Froebel created kindergarten. If you’ve ever looked at a piece of abstract art or Modernist architecture and thought “my kindergartener could have made that,” well, that may be more true than you realize.

The Seed of an Idea

Friedrich Froebel grew up wandering the dense forests of Thuringia in what was then Prussia. He fell quite naturally into a forestry apprenticeship and then worked for a time as a land surveyor. He was quite skilled at drafting and geometry, skills which would have dovetailed well with an architectural career. But he also spent time caring for and tutoring children, which led him to the teachings of Johann Pestalozzi.

An innovative educator, Pestalozzi believed children needed to engage in physical activity and active learning, not just rote memorization and repetition. He particularly emphasized the importance of drawing. Froebel worked for a time at a school based on Pestalozzi’s principles and built on what he learned there while also evolving his own ideas about the way children should be taught.

Among other things, Froebel realized he wanted kids to go beyond just drawing lines on pages — he wanted them to learn through the physical manipulation of objects. “Pestalozzi was especially busy with breaking down the two-dimensional world,” explains Tamar Zinguer, author of Architecture in Play, “but what Froebel did is break down the three-dimensional world.” Specifically, Froebel wanted children to play with educational toys, which was a fairly unusual notion in the early 1800s. Yet it was Froebel’s experiences outside of childhood education that would ultimately lead him to determine the shape and function of these toys.

For a time, Froebel worked with one of the world’s foremost crystallographers in Berlin — and this experience would fundamentally reshape how he understood the world. Where most people saw nature in big flowing organic shapes, like hills and plants and animals, Froebel zoomed in to study the straight lines and geometric forms of crystals. He came to see these as the building blocks of reality.

Finally, in 1837, Froebel’s experiences across different disciplines crystalized into a solid vision. At the age of 55, he founded the very first Kindergarten in Bad Blankenburg, Germany, a school for very young students.

The word Kindergarten cleverly encompassed two different ideas: kids would play in and learn from nature, but they would also themselves be nurtured and nourished “like plants in a garden.” There were literal gardens and outdoor activities, but the real key to it all was a set of deceptively simple-looking toys that became known as Froebelgaben (in English: Froebel’s Gifts).

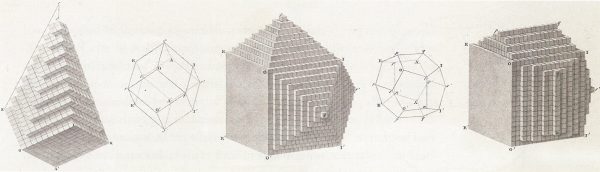

The Gift of Observation

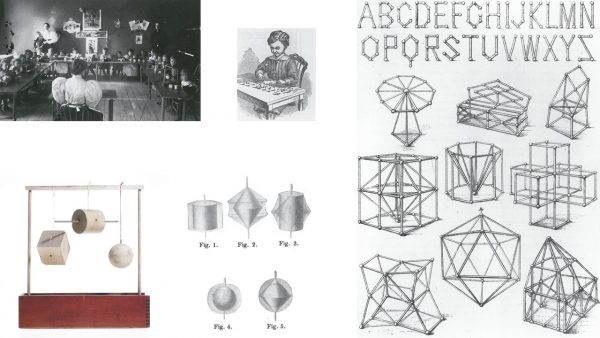

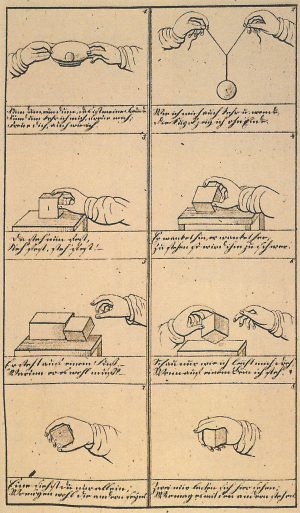

Froebel’s Gifts were meant to be given in a particular order, growing more complex over time and teaching different lessons about shape, structure and perception along the way. A soft knitted ball could be given to a child just six weeks old, followed by a wooden ball and then a cube, illustrating similarities and differences in shapes and materials. Then kids would get a cylinder (which combines elements of both the ball and the cube) and it would blow their little minds. Some objects were pierced by strings or rods so kids could spin them and see how one shapes morphs into another when set into motion. Later came cubes made up of smaller cubes and other hybrids, showing children how parts relate to a whole through deconstruction and reassembly.

These perception-oriented “Gifts” would then give way to construction-oriented “Occupations.” Kids would be told to build things out of materials like paper, string, wire, or little sticks and peas that could be connected and stacked into structures.

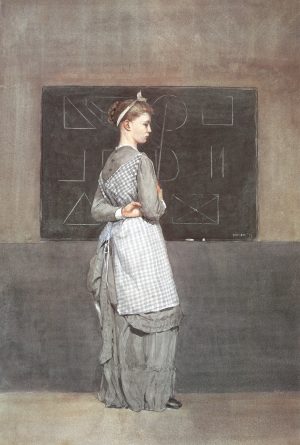

The final piece of this Froebelian puzzle was a block of clay. Malleable but solid, it could be shaped into virtually any form and thus allow for endless possibilities. But even with this highly flexible material, Froebel wasn’t trying to encourage the kind of creative, free and interactive play we tend to associate with childhood. He had his students sitting individually at desks — little workstations with grids laid out on them. Students were directed to make and unmake specific things according to a lesson plan.

The final piece of this Froebelian puzzle was a block of clay. Malleable but solid, it could be shaped into virtually any form and thus allow for endless possibilities. But even with this highly flexible material, Froebel wasn’t trying to encourage the kind of creative, free and interactive play we tend to associate with childhood. He had his students sitting individually at desks — little workstations with grids laid out on them. Students were directed to make and unmake specific things according to a lesson plan.

In a very structured way, these kindergarten lessons encouraged very young students to think abstractly, and to relate ideas, objects and symbols. A set of blocks could be used to teach counting, then be turned into a house and then be used to tell the story of a family living in that house. So kindergarten students learned to model the world in fundamentally different ways while using the same set of geometric forms, arranging and rearranging them to make new connections. Froebel’s kindergartens weren’t just schools — they were art schools that taught about shape and form and color. And when kindergarten graduates went out into the world, the world changed.

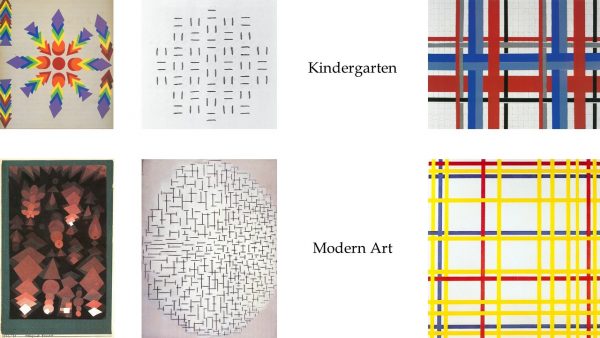

Training Aesthetes

“The kind of art that was being made in the 19th century is really different than the kind of art that was made after kids went to kindergarten,” explains Norman Brosterman, author of Inventing Kindergarten. Expressionist, Cubist and Surrealist artists like Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky attended early kindergartens. Others, like Piet Mondrian, encountered Froebelian methods as teachers. The resemblance of much of their work to illustrations in kindergarten teaching guides is uncanny at times. In some cases, a person might be hard-pressed to guess whether a given work was created by a kindergarten student (or teacher) or an abstract artist.

The impact also wasn’t limited to artists — kindergarten influenced designers, too. Walter Gropius’ first hire at the new Bauhaus design school was a kindergarten teacher. This world-changing educational institution had its adult design students doing geometric exercises much like those being done by kindergarteners. The effects of Froebel’s work on design education rippled out beyond Germany as well, influencing some of the world’s most famous architects.

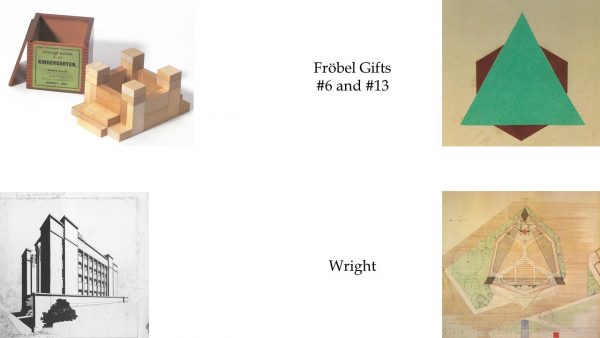

“Frank Lloyd Wright, the American architect, is the great child of the kindergarten,” says Brosterman. “You can see the kindergarten in everything Wright ever did.” Wright was born in 1867, around the time kindergartens were gaining traction in the United States.

Wright’s mom actually took classes in kindergarten education and Wright recalled that she brought him a set of Froebel’s Gifts at a young age. This was the moment, he later claimed, when he “began to be an architect …. For several years, I sat at the little kindergarten table ruled by lines about four inches wide. The smooth cardboard triangles and maple-wood blocks were most important. All are in my fingers to this day.” Growing up, Wright took courses in engineering, but he never formally studied architecture — and he wasn’t the only one to bypass a traditional architectural education on his way to fame.

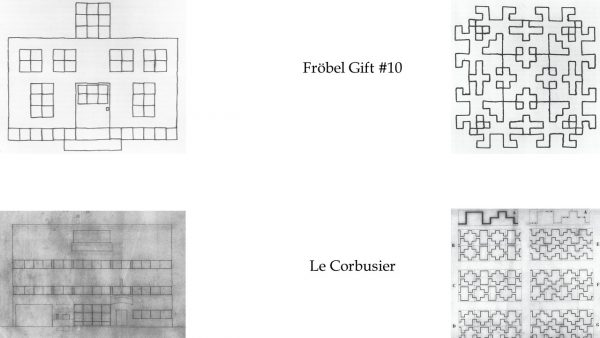

European Modernist Le Corbusier also never went to architecture school. He did, however, attend Froebelian schools in Switzerland. The gridded geometries and repeated patterns of his Modernist houses and apartment look a lot like exercises out of a kindergarten manual.

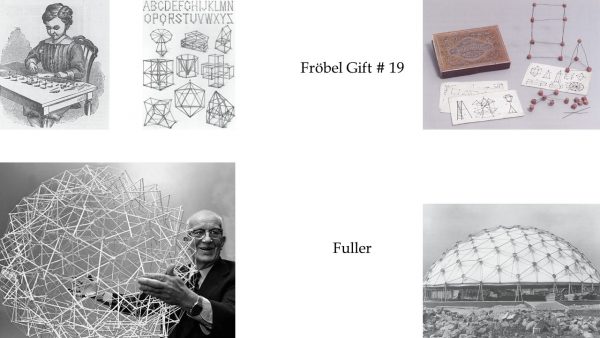

Buckminster Fuller, famous for pioneering geodesic domes, discovered his greatest engineering insight as a kindergartner while connecting Froebelian peas and sticks — nodes and rods, essentially. He couldn’t see very well, but he could feel that triangular structures were stronger. So while his fellow students build rectilinear shapes based on observation, he manually discovered the power of triangles, and built his very first space frame at a kindergarten desk.

Obviously, not everyone who attended kindergarten became a Frank Lloyd Wright or a Le Corbusier or Bucky — but the abstract lessons of kindergarten tilled and fertilized the ground so the seed of their ideas could find an audience in the world. “Abstraction was accepted fairly quickly in Europe in Paris,” notes Brosterman, “perhaps because children had already been doing a lot of the same kinds of things for many decades,” paving the way for the acceptance of Modernism.

The Seed of Destruction

In terms of 20th-century art and design, kindergarten was an absolute triumph, but Friedrich Froebel wasn’t there to see it. He got to witness the spread of his vision for only about a decade before it was cut short. In 1851, the Prussian government was cracking down on liberal thought and issued the “Kindergartenverbot” — a national ban on kindergartens — and Froebel died the very next year.

Still, while the ban slowed the expansion of kindergartens in Germany, it didn’t stop the idea from spreading elsewhere — if anything, it helped the approach spread faster. Out of a belief that women were naturally good at nurturing children, Froebel had cultivated a network of female teachers who would champion his ideas and emigrate with their knowledge to other countries. The women Froebel placed in charge of all those little budding abstract artists drew up and translated the lesson books that would be used to teach a generation of young artists and designers. By 1885, there were over 500 kindergartens in America, taught primarily by women.

Still, while the ban slowed the expansion of kindergartens in Germany, it didn’t stop the idea from spreading elsewhere — if anything, it helped the approach spread faster. Out of a belief that women were naturally good at nurturing children, Froebel had cultivated a network of female teachers who would champion his ideas and emigrate with their knowledge to other countries. The women Froebel placed in charge of all those little budding abstract artists drew up and translated the lesson books that would be used to teach a generation of young artists and designers. By 1885, there were over 500 kindergartens in America, taught primarily by women.

The spread of kindergarten wasn’t entirely straightforward, though. Indeed, the passion of some of kindergarten’s biggest proponents is part of the reason kids today don’t grow up with Froebel’s Gifts, those objects that were integral to Froebel’s vision.

The first kindergarten in the United States was built in Watertown, Wisconsin in 1856, but it was taught in German. Educator Elizabeth Peabody was inspired by this model and went on to found America’s first English-language kindergarten in Boston a few years later.

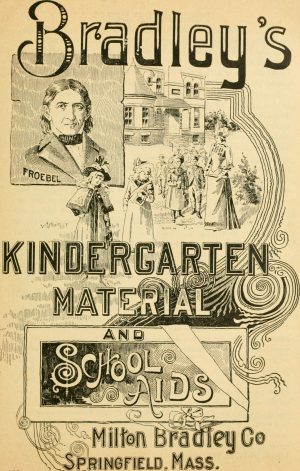

Peabody wanted to spread the teachings of Froebel to as many children as possible, and so she reached out to Milton Bradley, the famous board game maker and business magnate. She wanted Bradley to mass-produce Froebel’s Gifts, so they could be accessible to everyone. But where Peabody saw an educational ideal, Bradley saw a business opportunity. He and other manufacturers began adding new toys into the mix, trading on the popularity of the movement by calling their products “kindergarten” toys, regardless of how they fit into the Froebelian ethos. Within a few years, Peabody went from promoting the manufacture of kindergarten toys to speaking out against their proliferation: “the interest of manufacturers and of merchants of the gifts and materials is a snare. It has already corrupted the simplicity of Froebel in Europe and America, for his idea was to use elementary forms exclusively, and simple materials.” Even the word of “kindergarten” itself became a generic term — a catchall phrase for early childhood education of all different kinds.

Peabody wanted to spread the teachings of Froebel to as many children as possible, and so she reached out to Milton Bradley, the famous board game maker and business magnate. She wanted Bradley to mass-produce Froebel’s Gifts, so they could be accessible to everyone. But where Peabody saw an educational ideal, Bradley saw a business opportunity. He and other manufacturers began adding new toys into the mix, trading on the popularity of the movement by calling their products “kindergarten” toys, regardless of how they fit into the Froebelian ethos. Within a few years, Peabody went from promoting the manufacture of kindergarten toys to speaking out against their proliferation: “the interest of manufacturers and of merchants of the gifts and materials is a snare. It has already corrupted the simplicity of Froebel in Europe and America, for his idea was to use elementary forms exclusively, and simple materials.” Even the word of “kindergarten” itself became a generic term — a catchall phrase for early childhood education of all different kinds.

These days, most “kindergartens” are a lot different from anything Froebel imagined, and few kids encounter those early Gifts in any kind of sequence (if at all). Still, toy blocks never really went away — “the block is this … incredibly malleable toy that can be used in all of these different ways,” says Alexandra Lange, author of The Design of Childhood. She points out that other educators like Caroline Pratt and Patty Smith Hill saw the potential for blocks to do even more, creating interaction between children beyond their isolated, gridded desks.

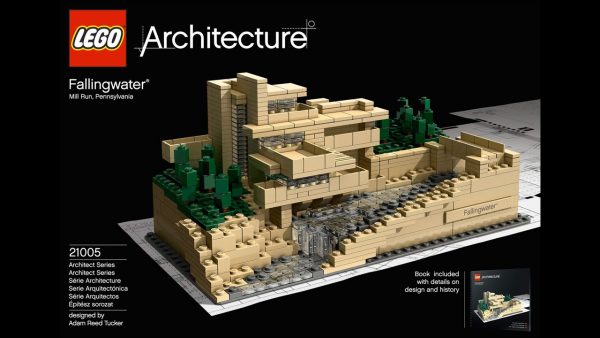

In some ways, all modern toy building systems reflect the influence of Froebel. Tinker Toys, Lego, Kinex — they’re all about understanding shape and form and making connections. Yet they also represent a departure from Froebel’s highly-organized and linear approach. These days, building toys are viewed more broadly as tools of the imagination — objects kids can use to assemble houses and castles and cities together, learning collaboration and creativity through construction.

Leave a Comment

Share