In early 2009, Christie’s International in Paris held a much-anticipated three-day auction from the private art collection of the late fashion designer, Yves Saint Laurent. The items up for sale were 733 pieces that Saint Laurent and his partner, Pierre Bergé, had amassed over five decades. The French press dubbed this the “sale of the century.”

Two of the most anticipated items of the event were a pair of bronze animal heads from China—one of a rabbit and one of a rat, each dating back to the 18th Century Qing dynasty. On the third and final day of the auction, the bronze heads went up for sale one at a time. The rat and the rabbit bronzes sold for fourteen million euros each to the same bidder—an art collector and dealer named Cai Mingchao. But when it came time to pay the bill, Cai had a surprise: he would not pay up. In fact, Cai had purposefully sabotaged the sale of the heads as an “act of patriotism” for China.

As it turns out, the rabbit and rat bronzes weren’t just decorative works of art destined to sit under a dusty glass case in some private collection. The animal heads had been looted from China during one of the worst incidents of cultural vandalism the country has ever seen. By stopping the sale, Cai was signaling to the world that China wanted its stolen heritage back. These bronze heads have become arguably the most prominent symbols of a growing concern around the repatriation of Chinese artifacts — these antiquities are highly sought after not for their artistic value, but rather the story they tell and meaning they hold for the government of China.

The Garden of Perfect Brightness

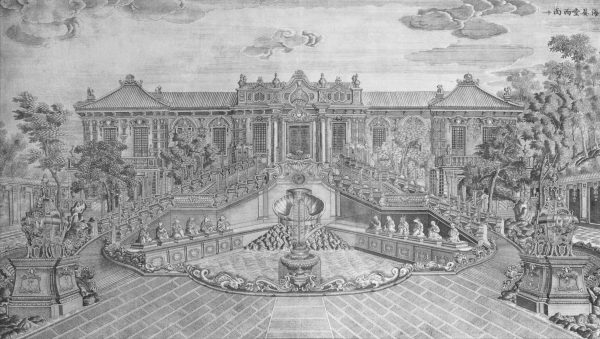

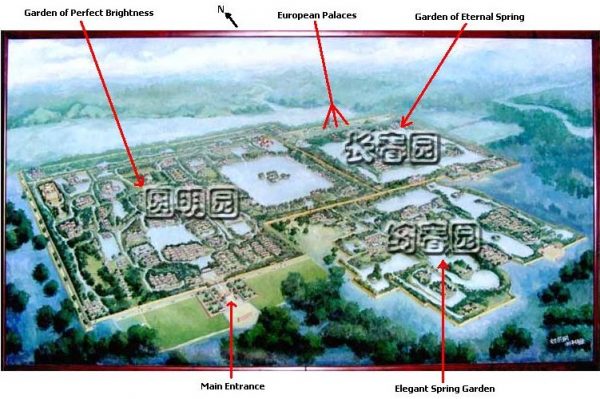

The bronze heads were originally part of a fountain featuring the twelve animals of the Chinese zodiac. These fountain heads would spout water out of a different animal’s mouth for two hours a day every day to signify the passing time. The animal fountain was a hybrid of European and Chinese design built by Italian Jesuit Giuseppe Castiglione for a European-themed garden within a much larger and more extravagant Chinese palace complex called Yuanming Yuan.

“The translation of Yuanming Yuan is often given as ‘the garden of perfect brightness’,” explains Patricia Yu, who studies the history of art at UC Berkeley. Yuanming Yuan was an immense garden complex first constructed in the 1700s for the imperial family of the emperor of the Qing dynasty. It was his “home away from home” (his primary residence at the Forbidden City) yet roughly the size of Central Park, made up of hundreds of pavilions and packed with all sorts of spectacular art and architecture. Yuanming Yuan may have symbolized imperial grandeur, but its story would be defined by tragedy.

Towards the end of the second Opium War in 1860, Qing officials captured and killed a British and French delegation; in response, Western forces advanced toward Yuanming Yuan. When soldiers arrived at the palace, a frenzy of looting took place. They spent days grabbing everything of value, and whatever they couldn’t carry they destroyed. They smashed vases and mirrors. There are even accounts of soldiers using rare manuscripts from the library to light their pipes. Even the emperor’s pet Pekinese dog was stolen from the palace and gifted to Queen Victoria, and renamed “Looty” in the process.

“By some estimates, maybe one point five million pieces were there — and all of that was taken,” says Frederik Green, Associate Professor of Chinese at San Francisco State University. Once everything of value was collected, the soldiers set fire to Yuanming Yuan. The complex was so large that it took three full days to burn down. Ironically, one of the few structures that survived from this resplendent Chinese palace was the stone facade of the European section where the bronze zodiacs had once stood — baroque remnants of an homage to Western architecture.

The Heads Emerge

Sometime during the looting, the bronze fountainheads were torn from their bodies, but at that point, they were just twelve of those 1.5 million pieces. No one paid them any special attention and they went missing in the chaos, presumably lost forever.

Lark Mason is a specialist in Chinese works of art and president of the Appraisers Association of America. But in 1987 he worked for Sotheby’s and he received a very interesting phone call from a couple looking to have a pair of antiquities valued. “They brought them into our gallery and I watched them as they opened these up and put them before me and thought, ‘Oh my gosh … these are wonderful, but what are they?'” he later recalled. After some research, he realized they were a part of twelve bronze heads from the European fountain of Yuanmin Yuan.

Later, in 2000, three bronze heads went up for sale at Sotheby’s and Christie’s. “We gave this auction the code name ‘Yuanming Yuan’, and that was kind of where all the trouble started,” explains Audrey Wang. Wang is the author of Chinese Antiquities: An Introduction to the Art Market and was also an Asian Art Specialist with Christie’s handling the sale of two of the bronze heads.

She says that since the 1990s Christie’s had always had imperial items for auction and she expected this sale to be business as usual. But it went very differently than the last time the bronzes had appeared on the auction block. What they hadn’t realized was that the sentiment around the bronzes had shifted. On the day of the auction, Wang was met with a sea of protesters trying to block the sale of the heads.

Imperfect Treasures

Every time these bronze heads pop up for auction they arguably send a very specific message to those in the know — that the right thing to do would be to return stolen cultural property back to its country of origin. But according to some people, including the artist Ai Weiwei, the zodiac heads aren’t valuable cultural relics but rather pieces of propaganda.

Ai Weiwei has been openly critical of the Chinese government’s mission to repatriate the bronze heads—so much so that he even created his own art piece called Circle of Animals / Zodiac Heads which was a reinterpretation of the bronzes.

To Ai, the animal heads aren’t Chinese cultural relics at all, especially if you consider that the bronze heads were actually designed by Europeans. “The work is made by a famous Italian priest working in the imperial court,” explains Ai, “so by its design and its craftsmanship and how it functions in this imperial garden it is not very Chinese. To choose that symbolic [of] Chinese treasure is ridiculous,” he maintains.

If you went back to 1987 when the first two bronze heads appeared on the scene, no one was looking for them. In fact, Chinese leadership wasn’t dwelling on the history of Yuanming Yuan at all. Yuanming Yuan was a mostly neglected site throughout the 1970s and 80s. Artists like Ai Weiwei took over the space and actually lived and worked in the forgotten ruins of the European garden. But that all changed after the Tiananmen Square Massacre in 1989. As Frederik Green explains, party elders interpreted the events as a challenge to Communist rule.

In response to those events, Chinese leadership felt that they needed to restore Communist Party loyalty in younger generations. They did this by reshaping China’s historical memory through a curriculum called Patriotic Education. “[The] Patriotic Education Campaign started shortly after the student movement in 1989, and it’s related to [a change to] history textbooks,” says Zheng Wang, a professor at the School of Diplomacy and International Relations at Seton Hall University, and author of Never Forget National Humiliation.

Patriotic education was intended to boost national pride and loyalty by teaching China’s youth a curriculum that both glorified the Communist Party’s accomplishments while also emphasizing how China has been a victim to foreign powers. At the heart of the Patriotic Education campaign was the Century of Humiliation.

As Wang explains, the Century of Humiliation is a special narrative in China that tells the story of the roughly 100 year period between the First Opium War and the founding of the Peoples’ Republic of China in 1949. During that time, China suffered considerably at the hands of foreign powers and this period is viewed as the darkest moment in China’s history.

The plunder of Yuanming Yuan was viewed as a key event in the Century of Humiliation because of the tremendous loss of cultural heritage. To some extent Yuanming Yuan is seen as a symbol of national humiliation and has been used as a site for patriotic education purposes. The goal was to make sure younger generations never forgot the lowest period in Chinese history or the destruction of Chinese culture by foreign invaders. Yuanming Yuan and the bronze zodiac heads were physical reminders of imperialist aggression.

But critics like Ai Weiwei have pointed out that if the Chinese government wanted to bring attention to the destruction of Chinese heritage, maybe it should look at its own actions. Just to take one example, during the Cultural Revolution, countless amounts of Chinese relics and cultural heritage sites were destroyed at the hands of the communist party. So to Ai Weiwei, focusing on the story of the bronze heads felt like an incomplete telling of history and that the Chinese government was manipulating the past to frame the communist party as the victims rather than the perpetrators of culturally destructive practices. “China has been victimized by the imperial states, but—still China is a bigger victim by its own government,” says Ai.

It makes perfect sense that illegally stolen relics should be returned to their country of origin, whether it’s Greece, Ethiopia, or China. Nonetheless, many people don’t necessarily like the way the “right thing to do” has itself been commandeered for political purposes. The bronze heads have the unfortunate burden of being both cultural heritage and propaganda, but as Patricia Yu says, any national treasure is at least a little bit of both. “Nothing is neutral [and] all of the values that we put upon objects and sites are constructed; they are negotiated; they are challenged.”

Return of the Head

In December of 2020, the State Administration of Cultural Heritage in China celebrated a big victory. To mark an important anniversary of the sacking of the palace complex, the bronze horse head went on display at Yuanming Yuan park. It was the first zodiac bronze to return to the grounds since they were looted from the site 160 years ago. It’s unclear whether the other bronzes will eventually join the horse on the grounds. As of now, seven of the twelve known bronze heads have been located and returned back to China. No one knows if the dog, rooster, dragon, sheep and snake will ever turn up.

Comments (8)

Share

Absolutely loved this episode. So interesting. The breadth of history and culture is fascinating. Thanks so much!

My favourite story about planning and the Chinese calendar is from Japan (and probably other countries in the Far East too). It has to do with the Hinoeuma.

The Hinoeuma is the Year of the Firey Horse (at least, that is its Japanese name). The last Hinoeuma was in 1966. The next one will be in 2026.

Women born in this year are said to be firey as the horses of the year. They will find no husbands. As a consequence of this, the number of abortions rose significantly in 1965. The number of children born in 1966 was substantially lower than in previous years. Classes that had 40 children now only had 30 children. It was a boon for those children allowed to live. They had much less difficulty getting into university and finding jobs on the grounds that they were demographically blessed.

This story was told to me by a Japanese man who was born in 1967. He, on the other hand, was demographically cursed. His parents had waited until the inauspicious year was over. Those classes that had once held 40 children now held 50. He was not a happy child. University and high school were harder to reach on account of greater competition.

What will happen in 2026?

What a pity the videos in this article aren’t watchable. A pretty apt and humourous underlining of the nature of this debate though!

Thanks for this great podcast. I used to history in an international British school in Beijing. The Yuan Ming Yuan was my favourite place to visit and to take schools trips – very green and spacious with beautiful views and a fascinating history and lots of stories. One story not mentioned in the podcast is that of the Fragrant Concubine, a Uighur princess who was forced to marry the Qing Emperor Qianlong. Her life is viewed very differently from Uyghur and other Chinese perspectives. Some stories suggest that mosques were built in the Gardens to try and make her feel at home and camel milk shipped in for her to bathe in. More info here:https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fragrant_Concubine

Great episode! Fascinating – and the timing with Lunar New Year was perfect too! I loved the quirky story about the Metal Rat years, too! Never would’ve heard that otherwise.

So glad that Metal Rat is gone, and looking forward to the year of the Metal Ox (from a proud Ox)!

I have a feeling in most countries including China, most art is stolen and preserved or destroyed. Definitely an interesting subject.

I am a Chinese Canadian who grew up in Hong Kong and was schooled in the UK. I feel offended by the suggestion that the desire to have the heads from Yuanming Yuen returned is a politically motivated act, and perhaps my feeling that the looted treasures should be returned was manipulated by government propaganda. I learnt Chinese history in high school in Hong Kong when it was a British colony (no communist propaganda there!) well before the handover and have always felt a sense of outrage by what the Western forces did at the end of the Qing dynasty, including looting and burning Yuanming Yuen. I saw the Horse Head when it was on display in the Lisboa Hotel in Macau and was moved by its presence back on Chinese soil. Ai Wei Wei does not speak for all Chinese, not certainly not for those of us who lived most of our lives in the West and have never lived under the Chinese government. I am offended in particular by the false equivalency put forth by him and seemingly agreed by the presenter about the Cultural Revolution. Firstly, any destruction occurred in the Cultural Revolution does not excuse the looting by the West; secondly, in the Cultural Revolution, objects were destroyed (tragically so) and cannot be “returned”. Ai Wei Wei’s well known bone with the Chinese Government seems to make EVERYTHING political and I don’t understand why your programme would make him the only Chinese voice about these objects. The looting of Chinese treasures by Western armies, frankly, in my view, was far worse than Elgin “removing” the “Marbles” to the UK for “safekeeping”. It was an act of war, deliberate destruction and looting committed by armed forces of foreign countries on Chinese soil. Why would you choose to interpret the attempt by Chinese people (we are more than the Communist government, you know) to have the heads returned in such a narrow scope and make that the focus of your show? Feeling a senes of pride and history as a Chinese person should not be reduced to “patriotism” as your programme suggested and these feelings are not exclusive to those who live in China and under the Communist regime. I am a fan of your podcast. I have never commented on yours or any other podcasts before. But I listened to this episode on my ride home today and am very very annoyed by what I think is a “small-minded” view of this issue and feel compelled to register my disapproval, particularly in this day and age when many Westerners choose to view and dismiss Chinese sentiments as “influenced” by the Communist Chinese government and brush us aside as it is. I am disappointed.

I appreciated the episode, but I don’t know why the Tiananmen Square massacre was referred to as an “event” in the episode. Here in the text it’s rightly called a massacre, but the actual episode glossed over it.