In 1939, an astonishing new machine debuted at the New York World’s Fair. It was called the “Voder,” short for “Voice Operating Demonstrator.” It looked sort of like a futuristic church organ.

An operator — known as a “Voderette” — sat at the Voder’s curved wooden console with a giant speaker towering behind her. She faced an expectant audience, placed her hands on a keyboard in front of her, and then played something the world had never really heard before.

A synthesized voice.

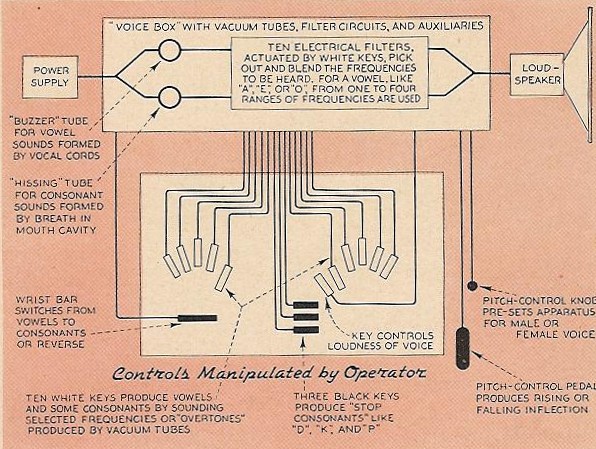

The Voder was an intricate machine. Each of the keys on the keyboard controlled a particular frequency band. Down below, the Voderette could access two pedals: one controlled pitch and the other controlled whether the sound would be muffled or crisp.

Operating the machine required incredible precision and skill. Voderettes would train for up to a year to make the Voder actually talk (or even sing).

The entire production was done live, with the keys and pedals of the Voder imitating the effects of the human vocal tract and producing the most basic building blocks of speech. The Voderette played them in a complex sequence, synthesizing speech in real-time.

The Voder was invented by an engineer and speech scientist named Homer Dudley, who worked at Bell Labs, a research facility owned by AT&T. During the 1920s and 1930s, Bell Labs was doing all kinds of research into the human voice, exploring how to synthesize, digitize, and compress speech for long-distance transmission.

The Voder was a novelty off-shoot connected to Dudley’s broader research, but it’s closely connected to a number of Bell Labs inventions that continue to shape our world today. Their influence can be seen in the realm of digital media, but also in the workings of the internet more fundamentally.

And on top of all that, Dudley’s inventions helped win a war.

A few years after the Voder’s debut at the World’s Fair, Japan launched an attack on Pearl Harbor in Hawaii and the United States entered World War Two. This conflict spanned the globe and created huge challenges in coordinating worldwide war efforts. Radio was one of the only possible ways to communicate, but it was insecure. Enemies could listen in. Secret messages of military importance needed to be encrypted.

At the very start of the war, the US military relied on an old-school piece of technology called the A3 Scrambler for its sensitive conversations. It worked by scrambling voice frequencies, swapping high frequencies for low and low frequencies for high, garbling the sound. But decoding these scrambled conversations was far too easy. German codebreakers were already listening in, descrambling talks between Allied leaders like Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill.

So the US government gave Bell Labs the mission of creating an unbreakable speech encryptor. Bell Labs, in turn, went to Homer Dudley, creator of the Voder, and assigned him the task of producing a functional solution as quickly as possible.

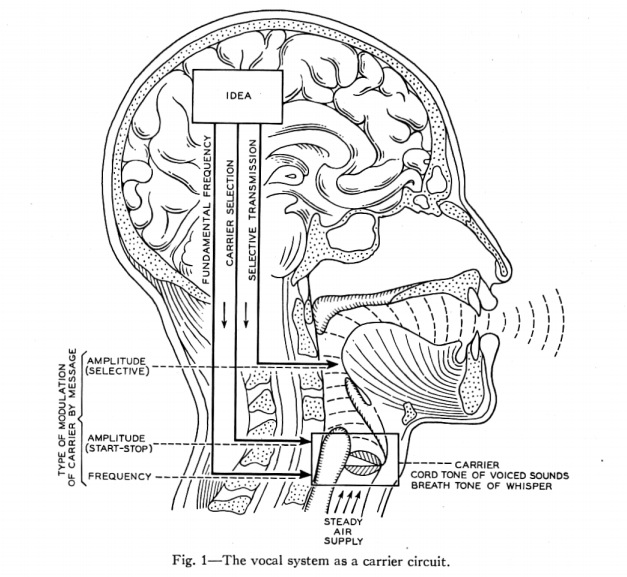

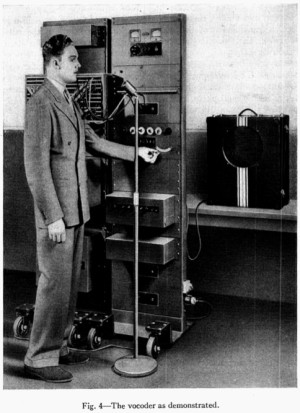

Dudley had a head start. He’d been working on technology related to this problem for years. It all went back to the Voder — and to a related invention called the vocoder (short for “voice encoder”). The vocoder could break down a human voice, separate it into its basic components, then compress and transmit those components via shortwave channel, and recreate it on the other side. This process was revolutionary, as it allowed the human voice to be digitized and then sent across vast distances.

But digitization and compression were only part of the puzzle, since the signal could still technically be intercepted and decoded. Dudley and his team had to add a layer of unbreakable encryption, leading to a much larger apparatus in which the vocoder would play just a part. It was called Project X… Otherwise known as The Green Hornet… Otherwise known as SIGSALY.

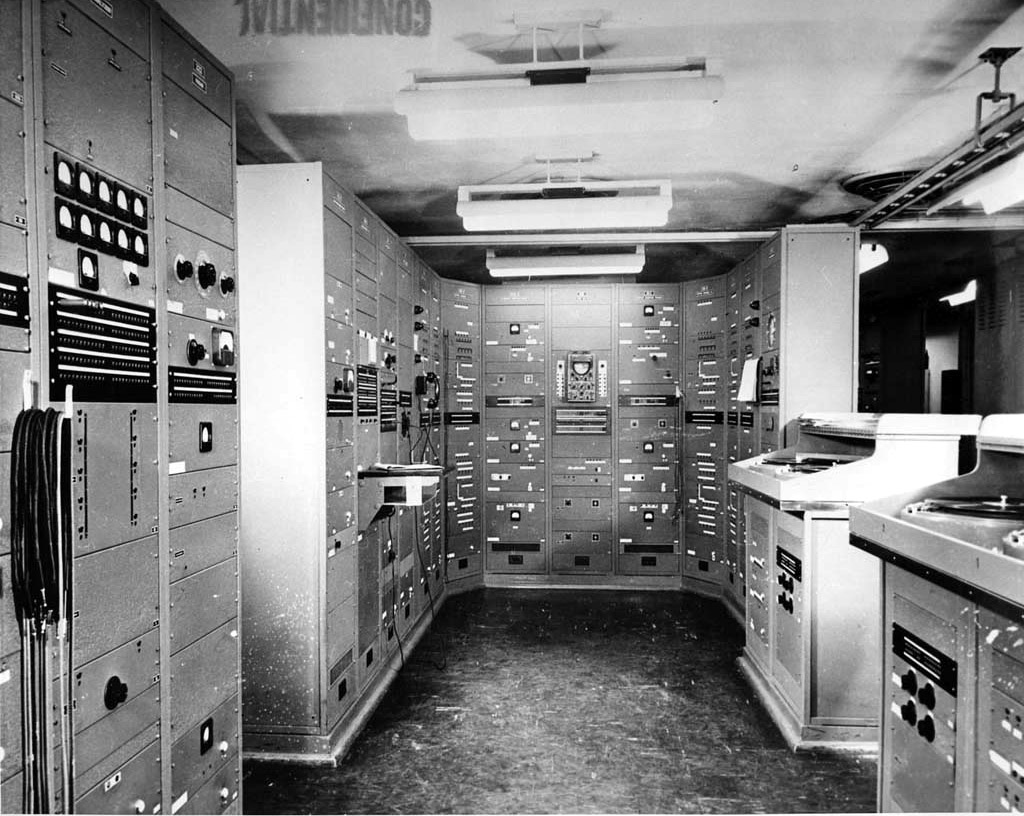

Each SIGSALY machine was enormous. It occupied about 2,000 square feet and was made up of 40 racks of equipment. It would only function within a very narrow temperature range and so required constant air conditioning. The devices were so important and technically demanding that a whole division of engineers was assigned to maintain the machines: the 805th Signal Service Company.

The first SIGSALY machine was installed in the basement of the Pentagon, then connected to several conference rooms upstairs. Operators below would man the machine during calls, coordinating with other staff above. Surface staff, in turn, interacted with and transcribed conversations between the military brass and Allies abroad.

This first machine in the Pentagon was ultimately connected to a network of a close to a dozen other terminals around the world, located in strategically important places like Hawaii, London, England, and, of course, Oakland. There was even one mobile SIGSALY terminal on a roving ship in the Pacific. This network allowed leaders in Washington, D.C. to talk, securely, with any other location that had a terminal.

To communicate with each other, the terminals required a shortwave radio connection, but also a Top Secret component devised especially for this system: a pair of vinyl phonograph records, each containing identical-but-random noise.

These were the (single-use) keys to the encryption and decryption process. On the sending end, noise was mixed with the components of the voice signal. On the receiving end, it was extracted. Each set of records used to facilitate these steps was given a code name, like “Red Strawberry,” “Wild Dog,” or “Circus Clown.” This naming system allowed both sides to coordinate and make sure they were using the right pair to encrypt and decrypt a given conversation.

So, imagine: President Harry Truman in Washington, D.C. wants to talk with Prime Minister Winston Churchill in London. The Pentagon keeps one record and sends the other across the ocean. At a specified time, each side’s signal engineers tune into WWV and synchronize their clocks. Then they set their identical records spinning at the exact same moment. On each end, the voices of these two world leaders are threaded through the SIGSALY terminal, mixed with a layer of noise, sent across the ocean via shortwave radio, then re-synthesized in a reverse process. After undergoing so much processing and traveling such a long distance, the voices didn’t sound good. But they were intelligible. Below you can hear an example of what a SIGSALY communication would’ve sounded like:

At the end of each conversation, the records were destroyed to protect against potential future decryption. Over the course of the war, SIGSALY facilitated around 3,000 secret conferences, requiring at least 6,000 records to be pressed, delivered, used and ultimately destroyed at the end of each call. Thanks to SIGSALY, Allied leaders could have completely secure conversations about the war.

Anyone attempting to listen in on the calls would just hear a buzzing sound, which is how the system earned one of its nicknames: “The Green Hornet,” after the popular 1940s radio show and its buzzing theme song.

SIGSALY was involved in virtually every major military operation after 1942. It was even critical in the planning of the Manhattan Project and the dropping of the atomic bombs over Japan. Engineers listening in on these calls had little idea what code words like “Manhattan Project” meant and didn’t understand the gravity of the information they overheard. They did know, however, that their role was crucial in helping the Allies win the war, even when that victory came at a grave cost.

At the end of the war, the SIGSALY terminals were dumped in the ocean for security purposes. But not before the military had developed successors that were smaller, simpler, and easier to set up. These new devices still worked on the same principles of encryption as SIGSALY and they were used for secure communications during the Cold War, the Korean War, and to negotiate the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Much of the information related to SIGSALY wasn’t declassified until the mid-1970s, when AT&T sued the US military under the Freedom of Information Act. But once it was public, technology that originated with SIGSALY made its way into other realms. Like your mobile phone, where a tiny chip descended from the vocoder compresses speech. Or on the internet, where mp3s and videos are compressed using technology that can be traced back to Dudley’s inventions too.

The vocoder has also found a whole new life in music, making voices sound strange and robotic. The instrument has been used by pioneering German electronic group Kraftwerk; electro-funk and hip-hop DJs of New York, like Newcleus and Afrika Bambaataa; Laurie Anderson; Daft Punk; the Beastie Boys; and many more.

In the end, the vocoder kind of came full circle. It started its public life as a silly novelty gag, making animal noises for crowds at the 1939 World’s Fair. Then, like the engineers who made, maintained and operated it, the Vocoder enlisted (so to speak), did its service and helped the Allies win the biggest war in modern history. Now it’s retired back to civilian life, making silly noises once again.

Listen to a two-part mix of Dave Tompkin‘s favorite songs that feature the vocoder down below and find a track list for the mix here.

Comments (9)

Share

Peter Frampton

This is the finest (and that’s saying plenty) 99pi episode, ever.

A great story, perfectly presented.

This epitomizes what I feel is wonderful about 99pi, the exploration of the amazing things that are mostly invisible.

Thank you.

Great Episode. the story of The Voder is really fascinating. I can totally understand that the people back 1939 went crazy about this machine (that coive must have been SO creepy to them…)

One question: What is the name of the song that The Voder sings in 2:13 – 2:45 ? It sonds creepy indeed.

Thanks for the clarification.

Till the next time.

Bye.

Agustín, it is Auld Lang Syne.

Thank you for the info, B. I did not know that song (and I did not understand the synthetized voice of the Voder, and did not understand the old scottish words). I have just checked it, and sounds really nice…

Doesn’t Daft Punk use a talkbox for some of their robot voices instead of a Vocoder?

Great episode!

The SIGSALY link is wrong, the correct url is:

https://www.nsa.gov/about/cryptologic-heritage/historical-figures-publications/publications/wwii/sigsaly-story.shtml

Great piece, except it refers to “digitizing” speech for the SISALY broadcast. Digital audio didn’t show up until the late 60s at it’s very earliest. I’d be curious how the SIGSALY process actually worked.

I am trying to research if there is any additional knowledge of the vocoder assigned to the White House. My great uncle said he operated that one at a secret location.