At its peak, the Berlin Wall was 100 miles long. Today only about a mile is left standing.

Compared with other famous walls in history, this wall had a pretty short life span.

The Great Wall of China has been around for 2500 years. So have the walls of ancient Babylon — although its most famous part, the Ishtar Gate, is actually in a museum in Berlin.

But even though the wall dividing Berlin into East and West was only up for 30 years, it had a huge impact on the psyche of the city. It broke families in two. In the decade that followed, more than 2 million people fled from east to west. East Germany was losing its most skilled workers as they sought jobs–and to reunite with their families–across the border. And East Germany was losing face with every East Berliner who chose to defect.

And that’s why, in 1961, East Germany closed its border to West Berlin with a wall. But this isn’t a story about the design of the Berlin Wall. This is a story about one design to get through it — or really, underneath it. Ralph Kabisch, then a 20-something-year-old university student, was there.

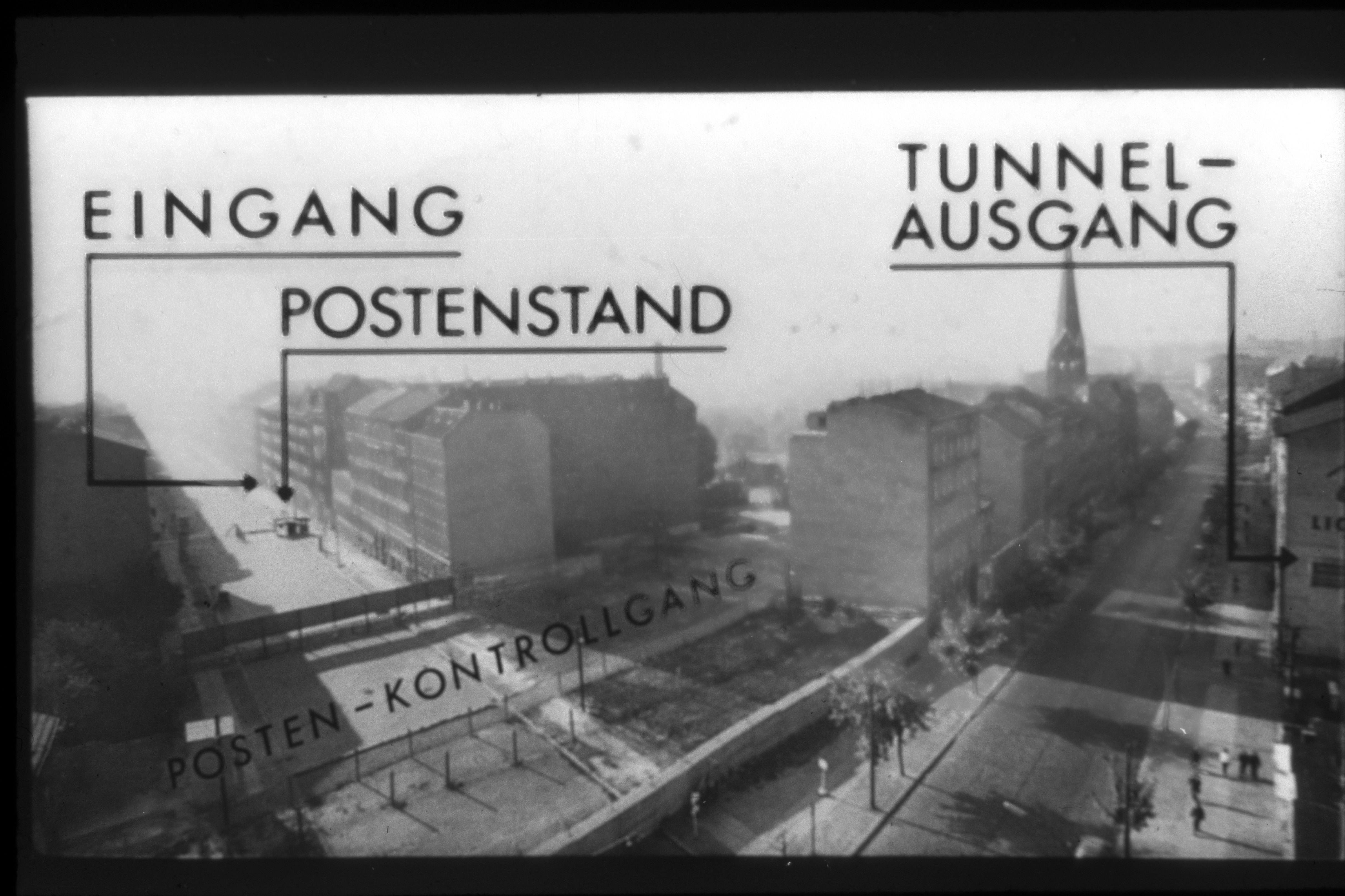

Now to be clear, Ralph and his crew were tunneling from west to east. They were tunneling into what was arguably the most militarized city in the world at the time.

Construction on the tunnel began at a defunct bakery along the border. (The bakery had closed because too many of its customers were stuck in the East). Near the bakery’s entrance, you could actually see the East German guard towers looming over the wall. And in that bakery, young Berliners were tearing into the ground, trying to dig a tunnel under the wall and into east Berlin.

Lessons learned from digging the tunnel

- To make sure your tunnel doesn’t flood, dig vertically until you get to the water table, and no further. Then dig forward.

- It is possible to move enough dirt to fill four eighteen-wheeler big rigs with garden spades.

- A password system can help expose Stasi spies.

- To keep the East German police from finding out about the tunnel, minimize people going in and out of the work site. In other words, live there.

- You can make a shower out of a faucet and a bicycle inner tube.

- A screwdriver will melt if it touches the power grid.

Ralph and his friends may not have had expertise in tunnel-digging, but they did have enough gumption — and love for their friends and family stuck in the East — to reach the other side. Thanks to them, 57 people escaped into free West Berlin.

Oddly, this tunnel served as a sort of apprenticeship for Ralph. After he finished university — and the Cold War ended — he became an international engineering consult on underground train systems all over the world. He helped build train stations in Korea, China, Thailand, Taipei, and Athens.

Comments (14)

Share

one of your best story – Thanks

You have inspired me to rewatch “Night Crossing,” a (Disney!) film I haven’t even thought of since it came out in 1982.

TL/DR: 2 families build a balloon to carry them from the East to the West.

What happened to Ralph’s cousin?

I took an Urban Planning class in Berlin a few years ago… the sandy soil is no joke. Most new buildings – especially ones built in the empty space left bey the wall – are basically boats that float in the quicksand.

Ralph’s cousin was on a school trip during the escape — bad timing. Disappointing for both of them. But she kept trying, and got out of the East a few years later.

I am a docent at Bethel Woods Center for the Arts in Bethel, NY, the site of the Woodstock Music and Art Fair in 1969. I am always surprised at how many guests from outside the US visit the site. A recent conversation with a German couple who grew up in East Berlin taught me that for those trapped there Woodstock meant more than music and mud. It was a beacon of freedom they said. This wall story is something I will tell on my future tours. Thank you

Hi there,

I’d like to give some feedback about the radioshow in general _because of_ this episode. tl;dr: I can now relate to the program again, so how can I give you my money?

I am a listener of the podcast from the very beginning and supported season 3 via kickstarter. I like the show because of the general idea of showing fascinating stuff in design and architecture that might not be obvious to us in the every day life, and because of the technical and artistic realization of the podcast.

But in the last couple of episodes, especially season 4, I felt like there was a shift from “beauty in design and architecture in the world” to “beauty in architecture in the U.S.”. Don’t get me wrong, the buildings and architectural designs you talked about where kind of interesting, but I could not relate to the topics that much anymore. I started loosing interest in the episodes.

But with this episode (and episode 102)…boom. The story, the drama, the images in my head… thank you for creating this episode and sharing it with us. Now I relate to the stuff you are talking about again and can’t wait for the next episode(s). Now I want to hear more and would like to trow my money at you.

Best

Benjamin

great story. one of my favorite 99% invisibles so far. thank you.

I was excited to listen to this but had to stop when I heard the narrator say that, in 1945, Berlin was “carved up into two sectors.” This is a pretty significant error that you should probably go in and re-track and also fix in the copy over at Slate.

Please watch Goodbye Lenin

My grandfather (who’s Belgian) actually helped people getting from East Berlin to West Berlin through tunnels. He doesn’t talk about it, though. I think he just doesn’t like talking about it, so I don’t know the details, sadly.

Nice to hear this story, though. I can now more or less image what it must’ve been, back then.

Dear Ralph, you’ll probably not read this but I live in Taipei and travel through your tunnels daily!

Great episode, thanks for sharing!

love this story, keep up the great work guys and gals

This episode was fantastic! In fact, episodes 1-104 have been great and I can’t wait to listen to 105+! Thank you.