Back in the 1950s, St. Louis was segregated and The Ville was one of the only African-American neighborhoods in the city. The community was prosperous. Black-owned businesses thrived and the neighborhood was filled with the lovely, ornate brick homes the city has become famous for.

Samuel Moore, who became a local alderman in 2007, grew up in The Ville. Moore’s father worked as bricklayer and helped build some of the stately brick houses in this area. “He was a great bricklayer,” says Moore. “He did quite a few jobs around this town and I still see some of my dad’s work — beautiful homes. Triple brick, three-story buildings that would cost a million dollars to duplicate.”

But driving around The Ville today, where Moore has lived for almost his entire life, the neighborhood looks very different. Some buildings are simply rundown or abandoned, but others are missing large chunks entirely. Walls have disappeared. The bricks are gone. “We call them dollhouses,” says Moore, “because you can look inside of them.”

In the past fifty years, the city of St. Louis has lost more than half its population. Vacancy has skyrocketed in The Ville and other neighborhoods on the north side of the city. Entire blocks in this area have returned to pastureland, punctuated by the occasional dilapidated building slowly surrendering to the landscape around it.

When Moore became an alderman back in 2007, he started to get calls from his constituents, complaining about these collapsing buildings. So he set out to discover why they were falling down. He figured it was probably just because they were so old. But then he noticed something strange about the “dollhouse” structures. They were surrounded by piles of broken bricks and debris — but something was missing.

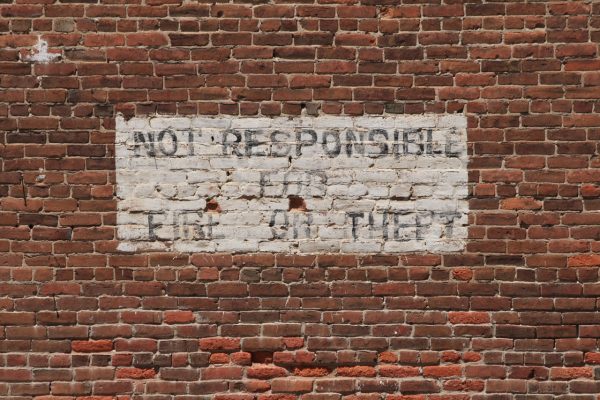

The piles of debris lacked whole bricks. Moore reasoned that someone must be taking them. Salvaged bricks are valuable. There’s a market for them just like there’s a market for the copper that gets stripped out of old homes. A pickup truck full of old bricks could be worth upwards of $300. But these bricks weren’t being salvaged legally, and the theft was happening at a massive scale in Moore’s district. He estimates over a thousand lots have had bricks stolen from them.

Brick theft is a problem. When a building’s bricks get stolen, the house usually can’t be resold. Even if it is a structure slated for destruction, the theft takes money out of the pockets of legal demolition workers. And brick theft stalls redevelopment because you can’t sell a building when you can’t guarantee it will be there next week.

But there’s also something intangible that’s lost with brick theft. The Ville has been home to famous African Americans like Chuck Berry, Tina Turner, and the opera singer Grace Bumbry. Moore says Grace Bumbry’s former home was stolen. A “lot of our history was taken away and stolen as well,” explains Moore.

Brick theft has been going on all across St. Louis since at least the 1970s. Whole buildings — whole blocks, big parts of whole neighborhoods — being carted off illegally and sold.

“How and where in the United States can somebody steal a whole building and not get caught?” asks Moore.

Brick by Brick

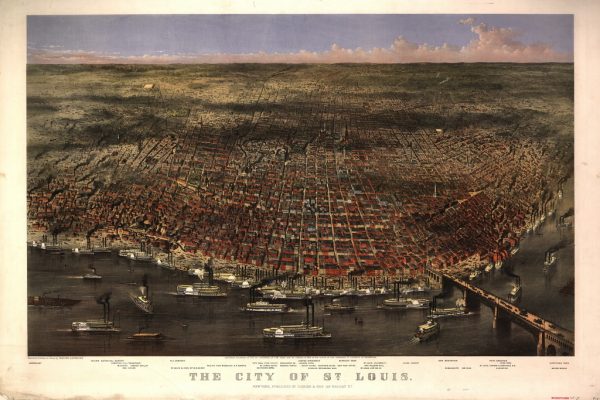

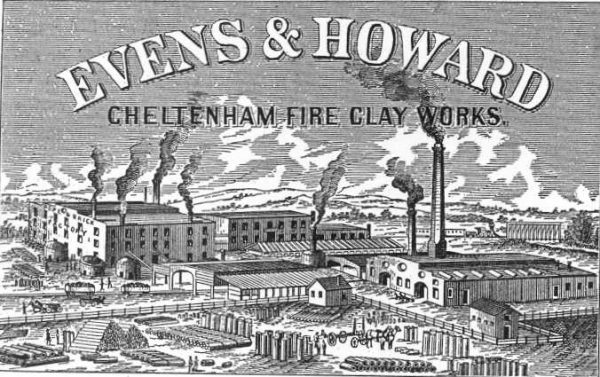

St. Louis has a long history with brick. It starts back in 1849, when a boat fire on the riverfront jumped into the city. Hundreds of wooden buildings along the river burned to the ground. The fire’s devastation led the city government to order that all new buildings be constructed with fireproof materials. Luckily, the city happened to sit on top of a lot of high-quality clay, as well as the coal needed to fire the kilns to turn that clay into brick.

Looking at old maps and images of the city it is easy to see the evidence of this thriving brick industry — smokestacks, pit mines, and beehive kilns dot the urban landscape.

The red clay industry was so big that people even dug mines in their own backyards. In the decades to come, waves of migrants from across Europe and the Southern U.S. flocked to the city. It was a boomtown.

“It’s a perfect storm of materials, labor, and industrial innovation that combined to make St. Louis into a brick producing powerhouse,” explains Andrew Weil, the executive director of Landmarks Association of St. Louis.

By 1890, St. Louis was home to the world’s largest brick-manufacturing company. Millions of bricks were exported across the country to build skyscrapers in Chicago and other buildings across the western and southern United States. Bricks were cheap and plentiful. And that meant that even modest working-class homes in St. Louis could have one-of-a-kind brickwork.

“They’re not just blank facades,” says Weil. “They have corbeling, extensions, recesses, and ornamental bricks built into them — pressed flowers or designs and string courses and things like that.”

But even as these beautiful brick homes were going up all across the city, the conditions for the city’s eventual semi-abandonment were also being put into place.

Segregation in St. Louis

Back in 1916, the St. Louis city government passed a law that zoned neighborhoods by race. The law was challenged and eventually struck down by the U.S. Supreme Court. Even then, local actors and institutions continued to segregate the city.

Soon, realtors were asking homeowners in St. Louis to sign something called race-restrictive deed covenants. These barred homeowners — and future homeowners — from selling the property to African-Americans and other minority groups.

Not only were African-Americans blocked from living in certain neighborhoods by these racist deed covenants, the City was also bulldozing African-American neighborhoods for urban renewal projects like the Gateway Arch.

In the 1950s, white residents had started to leave the city entirely. Their departure was facilitated by the recent development of the highway system and by the G.I. Bill which gave white veterans easy access to home loans, while largely denying black veterans the same right. White flight was happening all over the country, and St. Louis was no exception.

As whites rushed to the suburbs, the city’s population declined and its tax revenues plummeted. By the 1970s, African-Americans with means started moving out of the city too.

Yet many of the neighborhoods that went vacant were built with high-quality and durable materials. Bricks can last for hundreds of years.

The fallout from decades of racist housing policies and disinvestment effectively created communities where the bricks themselves are worth more than the homes they support.

The Rise of Brick Rustling

By the time Sam Moore became alderman in 2007, brick theft had already been going on for decades. But there hadn’t been much of an effort by the city to stop it. So Moore set out to figure out who was stealing bricks — and how. To start, he did what any detective would: he went on some stakeouts. He followed thieves, watching them steal bricks and then observing as they sold them to brickyards.

Abandoned houses represent remarkably easy targets. It’s not very hard to tear them down. Some people pry a few bricks loose with a screwdriver, then slide in a pipe, attach it to a chain, and pull. Other people use backhoes contracted for legal demolition jobs. They drive them over at night to knock down houses illegally, then come back later to take the bricks.

One of the more drastic methods of stealing bricks involves burning the buildings first. The fire destroys the wooden supports holding up the building and weakens the mortar between the bricks. When the fire department arrives to put out the fire, their high-pressure hoses sometimes knock down the walls and even clean the mortar off the bricks.

But stealing buildings is backbreaking work and it can be dangerous. Some people have been killed when the buildings collapse. But the danger has not deterred a lot of brick thieves, and neither has the law.

Brick theft is classified as a nuisance crime, kind of like breaking windows in an old building. It carries a maximum $500 fine and up to 90 days in jail — and given the amount of money that can be made selling stolen brick, a lot of people figure it’s a risk worth taking.

Supply and Demand

Barbara Buck, owner of Century Used Brick in St. Louis, says she is scrupulous about only buying legally salvaged brick. She typically buys from just a handful of trusted vendors. But Buck says there are other brick buyers that aren’t as careful as she is.

The supply of legally salvaged brick is driven mostly by city-funded demolitions. When the city runs out of money to tear old buildings down, more brickyards are willing to turn a blind eye to brick acquired in questionable ways. The legal supply of bricks goes down, but demand stays up.

Some of the salvaged brick goes to building or renovating new homes in St. Louis. But most of it heads to another part of the country entirely. There’s a big market for used brick in southern states like Mississippi, Louisiana, Florida, and Texas.

Gary McConnell owns McConnell Brick in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and he’s been buying salvaged brick from St. Louis for decades. When demand was at its highest, he was getting boxcars full of used brick from up north. New brick might sell for around $350 per thousand. Old brick, however, can go for twice that price.

There are a few reasons why there’s such a high demand for salvaged bricks down south. For one thing, in the 1960s and 70s, as neighborhoods in St. Louis were starting to hollow out, a new style of architecture in the South was creating a market for used brick.

Architects like A. Hays Town were influenced by Antebellum southern architecture, replicating old plantation homes using antique brick. Town’s designs called for used brick not just for the facades of homes but also for flooring, courtyard patios, and pool decks.

Even today, some neighborhoods in Baton Rouge require all new construction to use reclaimed brick. Demand for that weathered look has gotten so high that in some places only the most expensive homes can afford to build with it.

There’s another reason why so much used brick from St. Louis is in demand: not all bricks are created equal. The exterior layer of brick — often known as the “face brick” — produced in St. Louis is fired in such a way that helps it withstand the freezing winters in the Midwest. Interior brick is softer and can’t stand up to the elements. If you’re going to put used brick on a new home, there has to be someone at the demolition site separating out the face brick from the interior brick. That’s something demolition companies can’t (or won’t) pay for. The easiest thing for them to do is to ship all the bricks down to warmer climates, where even the softer ones can be used on the exteriors of buildings.

Today, the worst of the brick theft is over. Some of the brickyards that had a history of buying stolen bricks were shut down with the help of city workers, local activists, and representatives, like alderman Samuel Moore. Brickyards in St. Louis are now required to photograph whoever sells them the brick, along with the demolition permit for that job.

Doing Away with Dollhouses

Back in The Ville, there are various plans to deal with vacant lots in the neighborhood. Some open space has been converted into an urban farm. In other places, new housing is being built, but of a different type. Replicating those old brick homes would be cost-prohibitive, so buildings now use brick veneer. This clip-on brick works just like siding on a house. It’s a slice of used or manufactured brick attached to the wooden frame of the building, giving it the look of a brick home.

These homes, with their brick veneer, will be the new face of The Ville. They’re not as ornate as the old turn of the century houses that used to define this neighborhood.

But if their affordability gets more people to move in, to lower the vacancy rate, that’s what counts. Better to have a neighborhood full of life, even if the brick is fake.

Comments (8)

Share

Few of those ruined old castles and abbeys you see in England fell apart by themselves. Most were dismantled by stone robbers. You can see ruins like Corfe Castle with the nearby village all made of stone.

This was a big problem in Italy in the 1500s as well — Roman ruins were destroyed for limestone — apparently powdered lime was an important component of certain fabric dyes.

I really enjoyed this episode — I had no idea what to expect by the title, but I’m glad I clicked it anyways.

Interesting, eclectic story. My limited experience with brick involved finding matching bricks to fill an opening when we added on to our house. The house was built in 1961, but when I took a brick to the local brickyard, the operator knew the manufacturer immediately and sent me to the exact spot to find a few matches. Given the lapse of 40 years, the match wasn’t perfect but was close enough. I was truly amazed that it took only one trip to one brickyard to complete this task.

Have you heard the song, “Brick Thieves”, by the Saint Louis band Pokey Lafarge and the South City Three? I was waiting this whole episode for it to be mentioned!

Yeah that song was written for my film. Which the idea for this podcast kind of “borrowed” so they probably didn’t want to call too much attention to that.

Super interesting episode! I’m from St. Louis and I never knew it was the largest brick manufacturing city. I live in the south now and new construction homes are made almost entirely from brick but in St. Louis; new construction homes are almost completely vinyl siding which I find even more sad now considering the history in St. Louis. The old homes are so beautiful and it’s very sad to drive through these areas seeing the “dollhouses”.

I appreciate that this podcast covered this subject but it’s basically a wholesale adaptation (uncredited) of my documentary Brick by Chance and Fortune. You can find it on Amazon prime or Vimeo on demand. It would have been nice to get a shout out on the podcast since it was so obviously an inspiration for this piece.

Walter Johnson’s “The Broken Heart of America” brought me here. As a student of Saint Louis University’s graduate program in American Studies, I was more involved in other areas of study while The Ville was just a short trip–yet a million miles, really–away. Thanks for his book, this website, and so many rich sources that continue to educate me about this fascinating city.