During the parade of nations at the 2008 Beijing Summer Olympics, Greece’s athletes entered the stadium first, as per a long-standing tradition. But instead of following in alphabetical order, other countries came out in a sequence corresponding to the number of strokes each nation’s name had in Chinese characters. Jamaica, for example, was followed by Belgium.

For international networks covering the games, the parade proved a little tricky. Without the more familiar latin alphabetical order as a guide, NBC later posted the recorded footage to their website in the wrong order, sparking a short-lived message board conspiracy theory that the network had deliberately changed up the sequence in order to boost web traffic.

In much of the western world, alphabetical order is simply a default we take for granted. It’s often the one we try first — or the one we use as a last resort when all the other ordering methods fail. It’s boring, but it works, and it’s so ingrained that it’s hard to imagine not using it. But before you can order anything alphabetically, you need an alphabet.

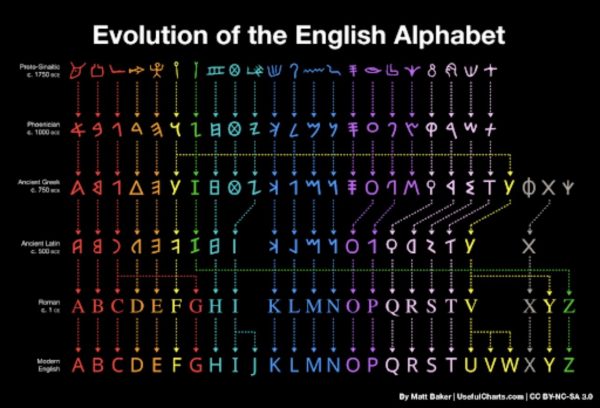

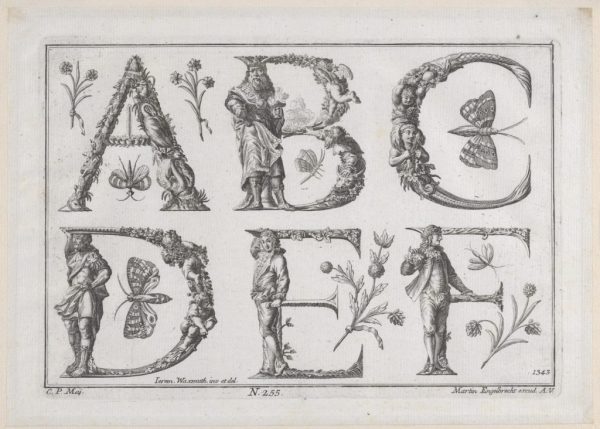

Timothy Donaldson, author of the book Shapes for Sounds, says the process of assigning sounds to symbols took a long time because, at first, all we had were pictograms — images that represented whole objects or concepts, like in very early Sumerian writing. So if you wanted to represent the idea of a fish, you drew a fish. Of course, this required an increasingly large amount of symbols, and eventually these pictograms changed and became more abstract.

By 2,800 BCE, certain marks began to represent syllables. Resulting ‘syllabaries’ could bring the number of symbols needed down into the hundreds, but a syllabary still isn’t an alphabet. The Egyptians had an equally large system of symbols which represented complex combinations of consonant sounds.

But then, around 1500 BCE, a semitic-speaking tribe in present day Syria had the idea to use one consonant per letter. Peter Daniels, an independent scholar specializing in early writing systems explains that this Ugaritic system still had no vowels at first, but it became what many scholars consider to be the first true alphabet. And its order would look quite familiar. It’s not all that different from the order of the Latin alphabet. The exact shapes of these Ugaritic letters would go through a lot of changes as they got adapted; early on by the Phoenicians, then the Greeks. and later the Romans. But the basic order was there from the beginning.

Why that order? No one is quite sure. There were competing orders, too, but Romans spread their alphabet more effectively, doing something they’re well known for: conquering much of their known world.

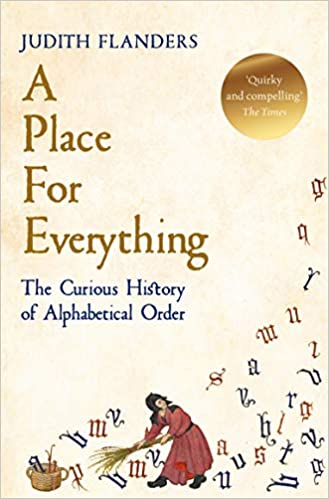

But despite its endurance for most of its history, the alphabet wasn’t initially used to order much of anything. Judith Flanders, author of A Place For Everything, a history of alphabetical order, says that in societies like ancient Rome and early medieval Europe, writing implements were still rare. So what mattered most was organizing knowledge in a way that helped you to memorize it. And that was usually much easier to do in the order you naturally came across the information, like: chronologically, or by size, or geography, or region, or hierarchically.

In the middle ages, for example, William the Conqueror’s Doomsday Book, which was a survey of all his subjects’ property assets, was divided into sections that started with the nobles and ended with the peasants. Church documents also tended to reflect this hierarchical view. And nowhere was this hierarchical worldview more apparent than in encyclopedias.

These kinds of books were primarily religious documents, written by archbishops and monks, who were attempting to create what they called a “mirror of the world” — starting with God, the angels and the saints at the front, and plants and inanimate objects at the very back. Humans were usually somewhere in the middle.

Theological books might have glossaries of difficult terms at the back, but these would be organized in the order they appear in the book, not alphabetically. Because in a world where knowledge was considered complete and holistic, the point was not to look up only the facts you needed, but to read the book from beginning to end.

One might occasionally come across a merchant’s invoice or one small part of a dictionary organized alphabetically. But even as late as the middle ages, alphabetical order was still so rare that anytime someone used it in a book, they would have to explain how it worked.

Little by little, alphabetical order would start to catch on. We can’t say why exactly, potentially because everyone who memorized the alphabet knew at least that much as a starting point: the order of letters. And this proved useful in a world where — increasingly — there was just too much to memorize.

In the 11th century, with the arrival of paper technology from China, writing stuff down was becoming a lot cheaper and more attractive than trying to memorize it. And for theology students at European universities, this facilitated a new form of learning, one in which arguments and counter-arguments included evidence. In defending a thesis, they were expected to cite their sources. So scholars began developing innovative ways to search for information like: indexing, pagination, methods for cross-referencing one thing with another.

Another big factor in the rise of alphabetical order was the arrival in the 15th century the printing press. Now that books were easy to copy, publishers realized they could make big money selling multiple copies of a single title. And the bestsellers often turned out to be reference books. At first, many of these reference books still strived to be “mirrors of the world” — organized hierarchically. But as famous enlightenment encyclopedists like Diderot incorporated more and more entries from more and more contributors, the easiest way to add a new entry without shuffling everything else around was just to organize it alphabetically.

But other members of the establishment weren’t happy about this new method of dividing up the world. Alphabetical approaches upended accepted hierarchies. They also enabled anyone literate to learn on their own initiative. It was up to the individual to decide what was worth discovering.

Today, organizing information by letter has become so commonplace that it often just goes unnoticed. But it still comes with its own biases. Just ask anyone whose name starts with a letter at the end of the alphabet. Academic economists are more likely to be cited, get jobs at prestigious universities and even win Nobel Prizes if their names are higher up the alphabet. Political candidates are more likely to win if they have early alphabet names rather than late names.

There is even something called ‘alphabet fatigue’, which is a phenomenon where a dictionary or encyclopedia team becomes less and less thorough as they move through the letters. Indeed, the first alphabetized edition of ‘Encyclopedia Britannica’ had three volumes, each of roughly equal length: and Volume 1 was just A through B.

In the 21st century, people have started turning to other ways of finding and sorting information. Even as much of the internet’s underlying infrastructure depends on it, no one uses alphabetical order to search through Wikipedia or to decide which article to click on next. Instead of indexes organized alphabetically, we have hyperlinks leading in a thousand different directions. Alphabetical order may have won while no was looking, but now, just as quietly, it’s being rendered obsolete. This once-dominant system may just be a really long phase.

Comments (11)

Share

Really curious as to whether Roman noticed what happened with alphabetizing the days of the week and decided to leave it or didn’t notice.

Same. I had to pause it and think for a moment…”wait, what? is ‘t’ before ‘s’?” Brain fart induced by a podcast, 😂

Did the Beijing Olympic PR office not distribute a list of the order? This sounds like a crazy example of the media folks not reading the documentation.

Did the 99% podcast never circle back to why the order was like it was in the parade? I assume it wasn’t random, as sort of inferred. Chinese has a dictionary, and like English dictionaries, there is an order to how words are ordered (by stoke order). Perhaps the countries were introduced in the order found in the Chinese dictionary rather than the English dictionary.

Where in Melvil Dui’s system does the The Invisible City fall?

Re: the song we use for the ABCs. The ABC song= Twinkle Twinkle Little Star= Baa Baa Black Sheep. So there are actually three using the same tune. I don’t know if this is because of the era in which they were written, but I have heard (but never verified) that a lot of American songs/hymns of the 1800’s were just poetry and then people would choose a common folk tune with a matching (enough) meter and then would sing it that way. So tunes and text were not nearly so rigidly “married” as they are now. This is why, I am told, the Star Spangled Banner is set to a popular drinking song of the day, for example. A lot of it was mix and match. This is also true of a ton of Christian hymns from the Revivalist era. In our hymnbook at church, there are a few texts that are set to two different tunes side by side, presumably because a couple of different folk tunes became particularly engrained for that text.

Also, not all languages have alphabet songs like ours do. When I was learning Spanish, we learned the Spanish names for all the letters (plus their few extra letters) using an American military call and response song. My Spanish teacher explained, almost apologetically, that Spanish doesn’t have a traditional song for teaching the name of the letters and the song had been made up by American Spanish teachers whose kids were struggling to learn an alphabet without the culturally expected “alphabet song”.

It is not just the ABC song. Each and every verse in the Doctor Seuss ABC book also can be sung to the tune.

Regarding the song we use for the ABCs: The ABC song= Twinkle Twinkle Little Star= Baa Baa Black Sheep. So there are actually three using the same tune. I don’t know if this is because of the era in which they were written, but I have heard (but never verified) that a lot of American songs/hymns of the 1800’s were just poetry and then people would choose a common folk tune with a matching (enough) meter and then would sing it that way. So tunes and text were not nearly so rigidly “married” as they are now. This is why, I am told, the Star Spangled Banner is set to a popular drinking song of the day, for example. A lot of it was mix and match. This is also true of a ton of Christian hymns from the Revivalist era. In our hymnbook at church, there are a few texts that are set to two different tunes side by side, presumably because a couple of different folk tunes became particularly engrained for that text.

Also, not all languages have alphabet songs like ours do. When I was learning Spanish, we learned the Spanish names for all the letters (plus their few extra letters) using an American military call and response song. My Spanish teacher explained, almost apologetically, that Spanish doesn’t have a traditional song for teaching the name of the letters and the song had been made up by American Spanish teachers whose kids were struggling to learn an alphabet without the culturally expected “alphabet song”.

Does the book explain how it became the dominant form of music notation?

The Japanese use kana-order (a-i-u-e-o | ka-ki-ku-ke-ko and so on) but there is an older kana-ordering system which is based on an old Buddhist koan (i-ro-ha-…) . It was used for a thousand years on acount of the fact that the koan has each of the syllables once.

Commodore Perry & his black ships may be indirectly blamed for the adoption of the first-mentioned kana-ordering system over the use of the elegant poem.

Oh, let me just say that I am so happy about this episode. I was getting worried recently that somewhere around the ownership change 99pi lost its grip – I felt that there were mainly (of course interesting, but still) interviews with book authors and runs of other podcasts.

This story while not in top 20 or even 50 of episodes, feels like good old 99pi. Keep up the good work.

Can’t wait to try out the party trick of telling people to alphabetize days of the week ;)