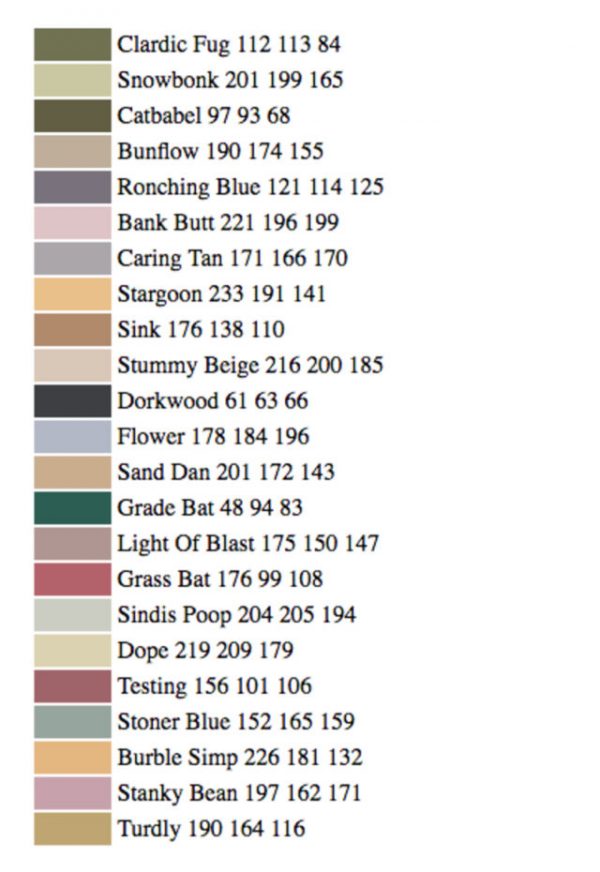

Research scientist and neural network enthusiast Janelle Shane recently tasked an AI to develop attractive names for 7,700 different paint colors. Annalee Newitz of Ars Technica reports that “the longer it processed the dataset, the closer the algorithm got to making legit color names, though they were still mostly surreal” as illustrated below.

In the end, Shane came to the following conclusions: “(1) The neural network really likes brown, beige, and grey; (2) The neural network has really, really bad ideas for paint names.” Robots may eventually get it right — perhaps when their parameters are tweaked to reflect some realizations humans have had about naming colors over the years.

Robin Egg Blue

In the early 1990s, an unlabeled crayon was included in Crayola boxes. Purchasers were asked to submit ideas for the color’s name. The winning selection, submitted by 8-year-old Christopher Straub, was Robin Egg Blue. Indeed, the color approximates the shade of the eggs laid by the American robin. But the first recorded use of Robin Egg Blue as a color name dates back to the late 1800s, a critical period in which new pigments were being developed at an unprecedented pace, and the cataloging of colors was becoming an issue of contention.

A Proliferation of Pigments

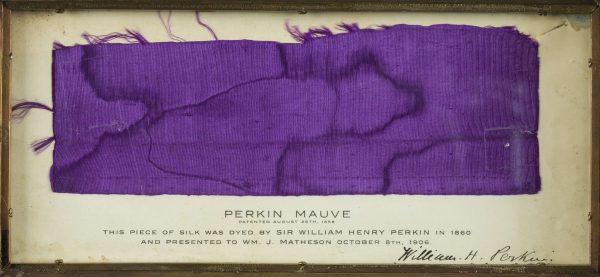

Until the mid-1800s, dyes were generally derived from natural sources like insects, roots and minerals. Then, in 1856, a young English chemist named William Henry Perkin accidentally created a synthetic dye.

While working on a treatment for malaria, “Perkin experimented with coal tar, a thick, dark liquid by-product of coal-gas production,” reports the Smithsonian. “His experiment failed but left behind an oily residue that stained silk a brilliant purple. He called the dye mauveine.”

As painting and photography enthusiast, Perkin immediately saw potential in his accidental find. It was more stable and consistent than many natural dyes but also easier and cheaper to mass-produce.

Soon, his new color was a hit in the fashion industry, spreading from Paris and London to the United States. Just as importantly, though, it opened the door to a whole new world of synthetic dyes.

The Nature of Names

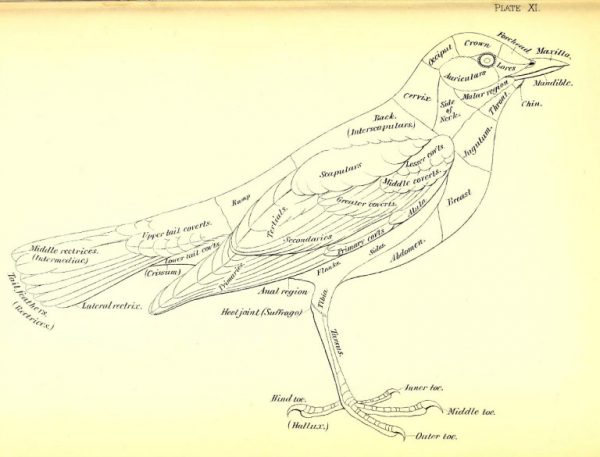

As more colors became possible (and easy) to create in the wake of the Industrial Revolution, the task of naming and organizing these discoveries also grew. An unlikely expert, Smithsonian ornithologist Robert Ridgway, spotted the problem in the course of his work and helped pave the way for nature-based naming systems.

Ridgway’s 1886 publication A Nomenclature of Colors for Naturalists : And Compendium of Useful Knowledge for Ornithologists featured 186 colors alongside diagrams of birds. As an observer of nature, he was already an expert at differentiating hues — it was an essential skill for distinguishing between species.

Ridgway was also a critic of existing color naming conventions. “The nomenclature of colors remains vague and, for practical purposes, meaningless,” he wrote, “thereby seriously impeding progress in almost every branch of industry and research.” He was annoyed by confusing names like Baby Blue and New Old Rose, but especially nonsensical names like Ashes of Roses and Elephant’s Breath. As he saw it, these didn’t make sense for practical or scientific purposes and should be avoided if at all possible.

Seeing broader potential for his efforts, Ridgway followed up with an expanded volume for public consumption (and 1,115 colors) in 1912: Color Standards and Color Nomenclature. Some colors he included “referenced birds, like Warbler Green and Jay Blue” explains Allison Meier of Hyperallergic, “while others corresponded to other elements of nature, as in Bone Brown and Storm Gray.” To be fair, not all were equally descriptive: Berlin, Paris and Italian blues, for instance.

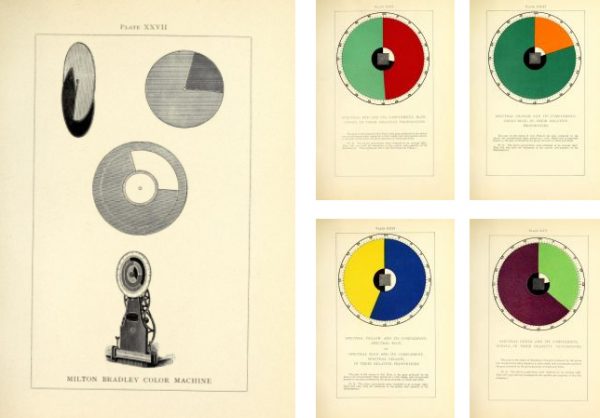

His work was inspired in part by Milton Bradley, famous maker of toys and games but also crayons, watercolors and the first mass-produced color wheels. Both innovators were interested in color standardization and education. Among other things, Bradley produced color wheels to help children understand how different colors could be combined.

Ridgway’s Color Standards became a standard reference guide for ornithologists but also other specialists in fields including mycology, philately, and food coloring. And while it was not adopted wholesale as a system, the ornithologist’s work on color was extremely influential and his “legacy lives on,” writes Daniel Lewis of Smithsonian.com with Ridgway’s “book evolving into the Pantone color chart relied upon by graphic designers, house paint creators, interior designers, fashion mavens, flag makers, and anyone looking to identify colors.”

Naming Another New Blue

Meanwhile, new pigments continue to be discovered. Earlier this year Crayola announced it is retiring Dandelion (a dark yellow shade) from its classic 24-pack of crayons — and it has just announced a replacement, said to be the “first new blue pigment in 200 years.”

“Mas Subramanian, a chemist and Oregon State University professor, became known in 2009 when his lab discovered the new blue pigment” writes Leanna Garfield of Business Insider. It was created by accident then picked up by the crayon company.

And, once again, Crayola is hosting a contest to name this new blue. Maybe it’s time to give Shane’s artificial intelligence another shot.

Comments (2)

Share

Really enjoyed the article, thanks!

Just a technical note on the crayon color: NPR published an article stating Crayola isn’t actually using the YInMn pigment in the crayon- “the pigment can’t be added to paints and materials just yet” and “it is in the process of regulatory approval”.

http://www.npr.org/2017/05/05/526808319/crayola-gives-the-people-what-they-want-a-new-blue-crayon

Wasn’t purple one of the more expensive/rare pigments “back in the day” as well? Interesting that it was the first synthetic dye and made cheaper/easier to produce, and by accident no less.