Computer modeling has helped revolutionize architectural design, enabling sophisticated and sculptural shapes rich with three-dimensional complexity. But while many such designs are driven by aesthetics, new modeling tools and algorithms can also be applied toward functional ends. The No Shadow Tower is one such structure, designed to reflect light and illuminate a space otherwise in shadow.

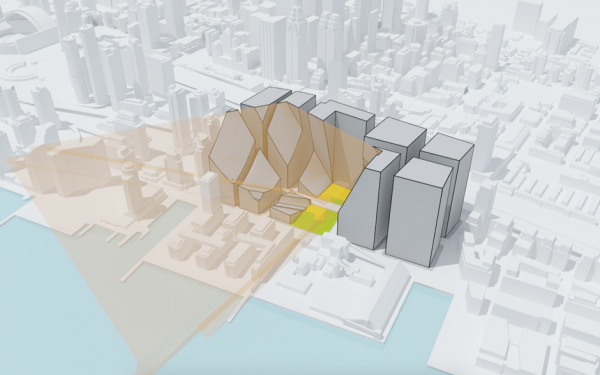

NBBJ, a global architecture firm, developed this project in response to issues of light access is growing cities around the world. Generally, more towers means less sunlight on the streets below.

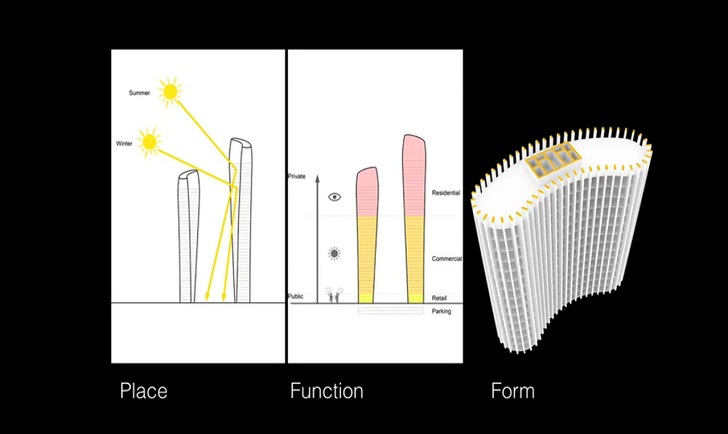

To get things started, the design team input a set of basic criteria — floor space, program, materials and so forth. They then instructed the software to generate solutions that would maximize the amount of light in a shared plaza space between two buildings. After a number of iterations (some strange and dysfunctional) and tweaks to the inputs and algorithm, an elegant pair of curved structures emerged.

The process sounds simple, but a lot of factors are at work, from basic engineering requirements to usability criteria. Furthermore, the reflected light needs to be diffused to avoid glare or other more dangerous complications (like concentrated solar heating effects).

This specific solution was engineered around the sun’s trajectory in London, where hundreds of tall towers are currently in the works, but other solutions could just as easily be generated for other regions. It has its limits, of course — the second building, for instance, still casts a shadow. Still, the project highlights how a limited resource (like sunlight) can be more strategically distributed in a city by design.

The idea of reflecting light to eliminate shadows is also not new (or entirely theoretical). In the early 1990s, Russia experimentally launched an orbital solar mirror, aiming to light up cold and dark northern areas like Siberia. Today, the town of Rjukan, Norway, uses mountainside mirrors to brighten its central plaza during darker months. Initially proposed nearly 100 years ago (and regarded as absurd by some), the project was completed just a few years back. Prior to this installation, the town was entirely devoid of sunlight for six months of each year.

Reflections, of course, are only one way to tackle public daylighting. In more conventional urban contexts, designers have long factored in shadows and light access, but these days “new tools and approaches allow us to respond to sunlight in a more refined way—one that is informed by behavioral science and based on real-time data,” reports Paul Kulig. New studies using data from social media have confirmed what researchers have observed for decades: urban activity is shaped significantly by daylight. But shade has a role to play as well, suggesting we can “move beyond a binary approach that views all shadows in a negative light, and instead employ the full palette of sunlight that is at our disposal to create spaces uniquely suited to their purpose.”

“Our streets and public spaces lie at the heart of our daily lives and deserve the same attention given to our homes, workplaces, schools and hospitals,” writes Kulig. Factoring in sunlight, “we can learn from new innovations in workplace, education, or healthcare design to deliver neighborhoods that support a wide range of economic activity, while also increasing livability and well-being.” We can also learn from historical research, like William H. Whyte‘s analysis of public spaces in his now-classic film The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces.

As for the No Shadow Tower — while still on the drawing board, the potential implications of this kind of modeling and control are far-reaching. Designers have to contend with variable environmental factors like weather and sunlight regardless, and data-driven reflectivity could prove a useful tool in their growing kit. This project is also a good general reminder that a building is not a neutral and self-contained object — for better or worse, it has impacts for the spaces around it.

Comments (6)

Share

Mirrors won’t work when clouds diffuse light, while there can still be a lot of light in open spaces.

Next to the village in Norway, I also love Ief Spincemaille’s work in Leuven: Residents of an apartment building there could order 30 minutes of sunlight every day, reflected via a mirror connected to the reservation system.

More here: http://www.iefspincemaille.com/There-is-the-sun

Let’s not forget the London ‘Walkie-Talkie’ building. It focused reflected light (presumably without computer modeling), enough to melt plastic in some people’s cars.

And (obviously less important, but…) corollary to this: Some of us LIKE the shade, darn it!

A fucking nightmare of rationalization:

“Sure, we created this shitty wind-swept plaza between these stupid blah corporate towers, but now we can bounce glare into it like sun from an asshole’s mirrored sunglasses! Are we Eco or what? Please like us! Please!”

I’ve seen cases in the past where sun light bouncing from towers (by accident) caused to overexposed a flora area near the tower causing deformities and deseases on the plants and threes, at it wasn’t Australia.

Is not a “bad” idea, but as architects I would not be surprise that they are deceiving themselves on ‘what’ and’how’ they are actually bouncing it….

And we all remember the Walkie-talky in London, but let ut not go there.