WARNING: Entering this area can expose you to chemicals known to the State of California to cause cancer and birth defects or other reproductive harm, including Benzene, a chemical used in urinal cleaners and Toluene, a chemical used in common household cleaning products. For more information, go to www.p65warnings.ca.gov.

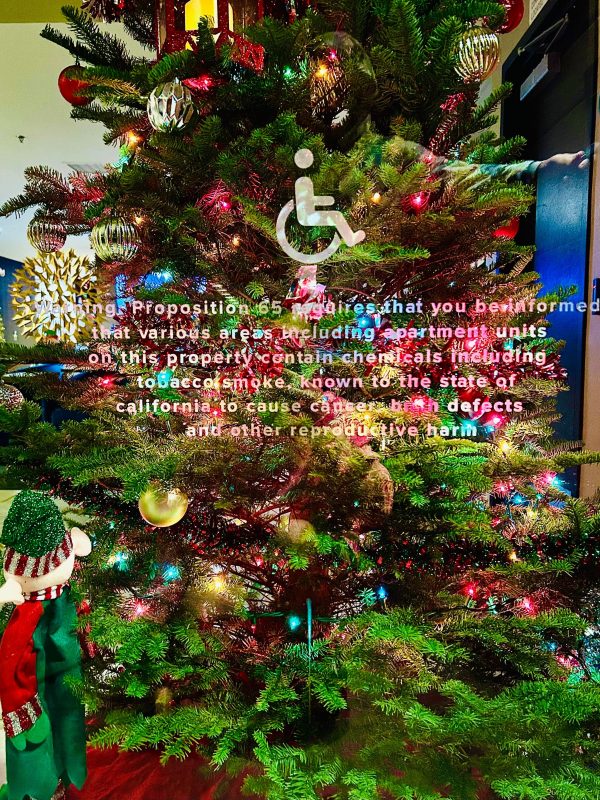

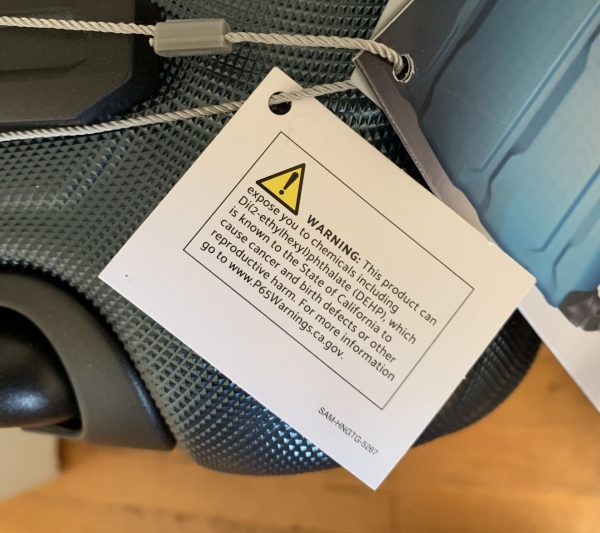

Intimidating Proposition 65 warnings like that one can be found on all kinds of products manufactured or distributed in the State of California. They can seem rather terrifying at first, but within the state, they are ubiquitous, on everyday objects from power tools to potato chips, dietary supplements, leather jackets, gas pumps, coffee tables, the list goes on. All of which raises the question: if these labels are on so many things, are they actually useful in warning us of real dangers?

Propping Up Legislation

David Roe was a senior lawyer with the Environmental Defense Fund for 20 years, and in 1985, he wrote a ballot proposition called Proposition 65 for the 1986 ballot. At the time, it felt like everything was poisonous — there were hazardous air quality warnings the vast majority of days in Los Angeles, not to mention deadly toxic spills. And, of course, the very real and persistent problem of lead in tap water.

The United States does not have a good track record when it comes to keeping people safe from toxic chemicals. Federal agencies like the FDA and the EPA were created to protect human health and the environment, but even in 1985 there were still huge gaps between the intent of laws regulating toxic chemicals, and impact — legislation like the Clean Air Act from 1963 wasn’t being very well enforced.

1986 was going to be a big election for the governor of California. The incumbent Republican governor had a really bad record on toxic chemical cleanup. And the democratic challenger was supported by a number of environmentally-progressive groups like the Sierra Club and the Campaign for Economic Democracy. Leaders from these groups believed that they could sway more left-leaning voters to come out to the polls and vote for their democratic candidate if they could write a ballot initiative addressing toxic chemicals and get it on the 1986 ballot. And David Roe was on hand to write just such an initiative.

1986 was going to be a big election for the governor of California. The incumbent Republican governor had a really bad record on toxic chemical cleanup. And the democratic challenger was supported by a number of environmentally-progressive groups like the Sierra Club and the Campaign for Economic Democracy. Leaders from these groups believed that they could sway more left-leaning voters to come out to the polls and vote for their democratic candidate if they could write a ballot initiative addressing toxic chemicals and get it on the 1986 ballot. And David Roe was on hand to write just such an initiative.

In order to appeal to voters, this initiative would have a very fine line to walk: it needed to have a strong environmental message, but also be simple to execute. It needed to be tough on toxic chemicals, but not so tough that it would be a burden on California businesses … which led David to come up with the Safe Drinking Water and Toxic Enforcement Act of 1986, AKA Proposition 65. The law wouldn’t ban toxic chemicals or even punish businesses for adding dangerous chemicals to their products or to the water system. It just said that in the state of California if a product contained a chemical that caused cancer or birth defects, there had to be a “clear and reasonable warning.”

This new law would broadly be applied to all products in California, rather than try to target individual chemicals. It also applied to businesses who distribute products into California from anywhere outside of the state. The idea was that no sane company would want to brand itself with a scarlet warning label saying they are intentionally poisoning you, and would instead develop alternatives. Ultimately, the goal wasn’t more labels, but rather no labels once companies figured out that this was the best long-term option in their own self-interest.

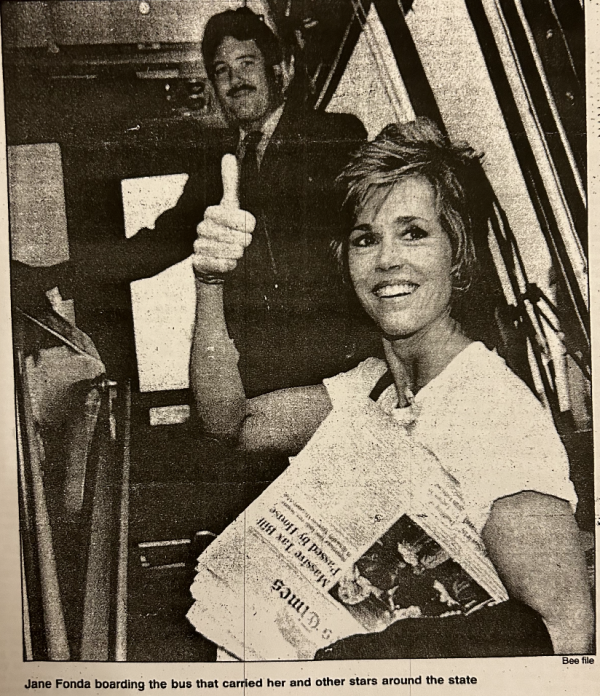

Proposition 65 was mainly opposed by big businesses with vested interests in avoiding more regulation. On the other side was a number of environmental groups and a whole host of Hollywood celebrities dubbed the “Clean Water Caravan.” Armed with some impressive endorsements and a clear environmental message, Proposition 65 passed in a landslide victory.

Prop 65 in Practice

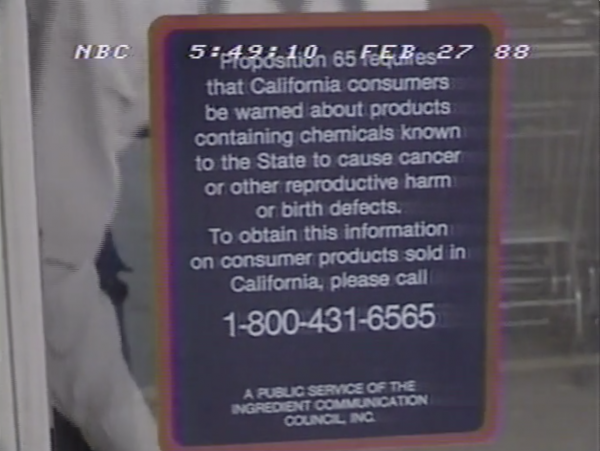

In the actual language of Prop 65, the drafters of the law never actually defined what a “clear and reasonable warning” meant. So David Roe says that when the law actually went into effect many businesses tried to weasel around this technicality by being purposefully opaque about warnings, putting up signs in fronts of stores rather than labeling individual products.

But this kind of intentional obfuscation was quickly determined to be illegal. A formula of words was needed, and wound up being determined by the California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment:

WARNING: This product contains chemicals known to the State of California to cause cancer and birth defects or other reproductive harm.

In order to avoid such a warning label, lot of big companies did exactly what the architects of Prop 65 intended: they reformulated their products to avoid using toxic chemicals. Companies like Coca-Cola, Pepsi, and Gillette all changed to get out of having to label products.

But because people who violate Prop 65 don’t face criminal penalties, others chose to face lawsuits — and there were a lot of them. The Attorney General is the principle prosecutor, but Prop 65 states that any private individual “acting in the public interest” can file a lawsuit against any company exposing consumers to toxic chemicals without properly warning them — meaning everyone could enforce the law.

But because people who violate Prop 65 don’t face criminal penalties, others chose to face lawsuits — and there were a lot of them. The Attorney General is the principle prosecutor, but Prop 65 states that any private individual “acting in the public interest” can file a lawsuit against any company exposing consumers to toxic chemicals without properly warning them — meaning everyone could enforce the law.

If a product doesn’t have a warning label on it, any private individual can test that product for themselves, and if they find a significant level of a toxic chemical, they can file a lawsuit against that business. If they win, they get to collect a penalty fee which the defendant has to pay. It’s the responsibility of the business being sued to prove their product is under the Prop 65 limit, and if they can’t: they are liable to pay up to $2,500 per violation, per day, which could add up fast. Some growing businesses tried their luck, only to be sued out of existence.

Today there are over 1000 chemicals on the Proposition 65 list, and the reality is: a lot of things have some of these chemicals in them. For some businesses, especially smaller ones, it can be difficult, expensive, and ultimately unrealistic to test for all of them. According to one 2019 study, Prop 65 lawsuits were costing California businesses around $30 million a year. And 76% of that $30 million went straight to attorney’s fees, so lawyers ended up being the primary “winners,” not ordinary citizens, incentivized to act as “bounty hunters” to secure fees.

Today there are over 1000 chemicals on the Proposition 65 list, and the reality is: a lot of things have some of these chemicals in them. For some businesses, especially smaller ones, it can be difficult, expensive, and ultimately unrealistic to test for all of them. According to one 2019 study, Prop 65 lawsuits were costing California businesses around $30 million a year. And 76% of that $30 million went straight to attorney’s fees, so lawyers ended up being the primary “winners,” not ordinary citizens, incentivized to act as “bounty hunters” to secure fees.

The amount of lawsuits has become such an uphill battle that many businesses just take the easier route and cover their bases, adding labels to all kinds of things. Critics of Prop 65 describe it as a well-intentioned environmental law that has caused unnecessary collateral damage. Even those who support Proposition 65 admit that as a warning system, these labels have a lot of flaws.

Props to Prop 65

Defenders of Prop 65 emphasize that those ubiquitous warning signs are just the most conspicuous part of a hidden system that actually is working — businesses, behind the scenes, continue to reformulate their products, and of course, they don’t publicize it (which would be a tacit admission their old formulations were potentially dangerous).

Defenders of Prop 65 emphasize that those ubiquitous warning signs are just the most conspicuous part of a hidden system that actually is working — businesses, behind the scenes, continue to reformulate their products, and of course, they don’t publicize it (which would be a tacit admission their old formulations were potentially dangerous).

David Roe, for instance, points to a striking example from around the time when Prop 65 was first passed. It involved the amount of lead – a substance dangerous at any level – that was allowed in the pipes that carried our drinking water. Under federal law, “lead free” meant less than 8% lead, which, if you think about it, is mind-boggling. Prop 65 was able to act as a safeguard to gaps like this in federal regulations by encouraging companies to regulate themselves. A lot changed thanks to Prop 65, including: water meters, galvanized pipe crystal decanters, foil caps on wine bottles, brass keys, hand tools, exercise weights, raincoats, electrical tape, electrical cords, bike locks, the list goes on.

When companies remove dangerous chemicals to meet Prop 65 guidelines, it’s not just Californians who benefit from that. The same products are made safer for the rest of the country as well. And because the state of California has the 5th biggest economy in the world, producers globally are pushed to do the same.

Still, some people want changes — ways to make the laws easier for businesses to navigate, or make the warning labels more specific and helpful, or adjust things to reduce the number of frivolous lawsuits. Even supporters of the law recognized that there may be problems with how it works, but at the moment, Prop 65 is still the best we have.

Leave a Comment

Share