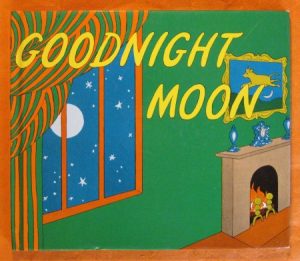

To celebrate the 125th anniversary of the New York Public Library, a list was published of the ten books that had been checked out the most in the history of the library — and most of these were children’s books, like The Cat in the Hat and Where the Wild Things Are. Curiously absent from the list, however, was a familiar classic: Goodnight Moon. According to Slate writer Dan Kois, this wasn’t a function of popularity, but the product of a decision made by a particular children’s librarian, who kept it off the shelves of the NYPL system for decades, from the 1940s through the early 1970s.

New York librarian Anne Carroll Moore is a complex figure, and while her dislike for this book might make her sound like a villain, she actually played a huge role in making libraries more accessible and inviting to children. Jill Lepore, host of The Last Archive, says all of those spaces we take for granted in libraries, oriented towards kids, arguably trace back to Moore. From a young age, Moore loved to read and her family was wealthy enough that her house had books in it that she could read, but alas for other kids at the time, libraries were oriented toward adults as well as boys. Children were too young to read, the argument went, so they had no need to enter. The libraries that did have books for kids often tucked them away to be checked out by adults for their children, not toyed with.

New York librarian Anne Carroll Moore is a complex figure, and while her dislike for this book might make her sound like a villain, she actually played a huge role in making libraries more accessible and inviting to children. Jill Lepore, host of The Last Archive, says all of those spaces we take for granted in libraries, oriented towards kids, arguably trace back to Moore. From a young age, Moore loved to read and her family was wealthy enough that her house had books in it that she could read, but alas for other kids at the time, libraries were oriented toward adults as well as boys. Children were too young to read, the argument went, so they had no need to enter. The libraries that did have books for kids often tucked them away to be checked out by adults for their children, not toyed with.

According to editor and children’s author Jan Pinborough, when Moore moved to New York, she became one of a small number of librarians advocating for letting kids into libraries. They wanted to offer more opportunities to working-class kids in particular, who had limited opportunities to read. At a handful of libraries, they began experimenting with stocking a corner with children’s books and then making that area just for kids.

Moore radically expanded on this experiment. In 1911, the New York Public Library opened its iconic main branch at the corner of 42nd Street and 5th Avenue, and it featured a dedicated children’s reading room run by Moore. She outfitted it with furniture, benches, and other things for small kids. The shelves were decked with fresh flowers and other friendly flourishes. There would be story hours, not just quiet reading, and thousands of books — not locked away for adults, but left on display for children.

This new reading room was an instant success and the idea began to spread. Within just a few years, over 1/3 of the volumes being loaned out by the system’s branch libraries were books for kids. Similar rooms began to appear in libraries around the world.

This new reading room was an instant success and the idea began to spread. Within just a few years, over 1/3 of the volumes being loaned out by the system’s branch libraries were books for kids. Similar rooms began to appear in libraries around the world.

Still, there was a catch — which is the Anne Carroll Moore’s vision also about what counted as children’s literature and what didn’t. Moore shared her picks publicly to help other librarians decide what to buy. She had created the market for kids literature and then went on to dominate and influence it for years to come.

Moore had strong feelings about what was good and bad for kids — she had high standards for the kinds of literature to be included, but that cut both ways, sometimes resulting in popular, relatable titles getting snubbed. Her favorites were most once upon a time style stories — things that were warm and sweet and lovely and would give kids a break from everyday life. Comforting plotlines in the countryside were the norm, not ones set in urban settings that reflected common experiences.

Moore had strong feelings about what was good and bad for kids — she had high standards for the kinds of literature to be included, but that cut both ways, sometimes resulting in popular, relatable titles getting snubbed. Her favorites were most once upon a time style stories — things that were warm and sweet and lovely and would give kids a break from everyday life. Comforting plotlines in the countryside were the norm, not ones set in urban settings that reflected common experiences.

In parallel, though, a group of preschool teachers began going their own way, working just down the street at a progressive school called Bank Street. The school was run by the educational reformer Lucy Sprague Mitchell, and, according to children’s literature historian Leonard Marcus, at Bank Street they believed that children were curious about the immediate world around them, not just magical realms. So they wrote children’s books with less emphasis on flights of imagination than on everyday experiences. They rarely had plots, but instead were more like games — interactive and open-ended. A typical Bank Street story might invite the child to imitate the sound of a train going by instead of sitting and listening to a once upon a time story.

None of which was to the liking of Anne Carroll Moore. She made sure Bank Street’s earliest titles were kept off the shelves of the NYPL. But there was another problem with Bank Street’s earliest children’s books: They were stiff and formulaic.

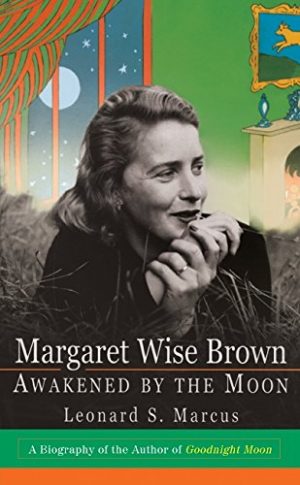

But in the 1930s, a teacher came to the school — a woman who would go on to author Goodnight Moon — with a vision for change. Margaret Wise Brown managed to make Bank Street stories more engaging by turning them into poems for children, who she believed were still open to novel ways of seeing and expressing the world around them. Children’s author Mac Barnett says she also used page turns to surprise the reader, creating a sense of unexpected discoveries and making connections between previously disparate ideas.

Goodnight Moon was based on a practice she used herself, a process of listing all her favorite things in her room as a way to inspire herself to get up in the morning. For the book, she reversed the ritual — there’s no plot, tension, just a list of things in the bedroom of a little bunny then which you then start wishing goodnight.

By the time this book came out, Anne Carroll Moore had technically retired, but still held a lot of influence in the public library system. Moore saw Goodnight Moon as a horror, and she did not recommend it. At first, the book sold a handful of copies. She was never convinced that this was a worthwhile volume for kids, but as time went on, Goodnight Moon became recommended by non-librarians as a way to help get kids to sleep, and slowly became more and more popular. Finally, in 1972, the NYPL began stocking copies on its shelves. Today, tens of millions of copies have been sold in bookstores as well.

Despite the feud between Anne Carroll Moore and Bank Street writers like Margaret Wise Brown, the books that made the NYPL’s 125th anniversary list owe something to both camps.

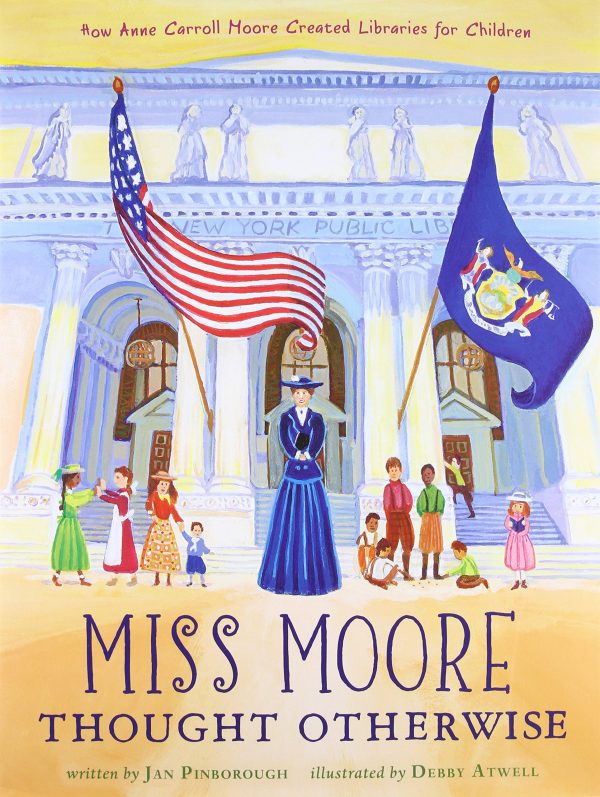

So perhaps it’s fitting that today there are children’s books about both Moore and Brown. Miss Moore Thought Otherwise, by Jan Pinborough, chronicles the incredible ways Moore got books into the hands of children. While The Important Thing About Margaret Wise Brown, by Mac Barnett, shows how Brown persevered to write books beloved by parents and children all over the world.

Leave a Comment

Share