A hot trend in the world of office furniture is “resimercial” design, the word representing an awkward mash-up of residential and commercial. Resimercial items are intended for workspaces but that feel like something you would have at home, comfortable and familiar.

One reason for their recent popularity is the fact offices have to compete with everywhere else. Remote work has been on the rise for a couple of years now. The Bureau of Labor Statistics says 35% of American workers were at home in the early days of the pandemic. Many of these people aren’t thrilled about the idea of going back to a physical office. In fact, a Gallup survey found that 30% of office workers never want to return. Another 60% want to stay on a hybrid model, only going to the office a few days a week. A different study found more than half of middle income workers were thinking about switching jobs, and that remote flexibility was a big part of their decision.

Those numbers make it clear the office is at this inflection point. And that’s why, it makes sense that office designers are promising a lot right now, including an office of the future that’s more comfortable, more pleasant, and more tailored to the needs of workers. And this is not the first time that designers have tried to fix the existential malaise of office workers with furniture. In fact, back in the 1960s, we had a lot of the same problems — white collar workers weren’t happy, they didn’t feel inspired or satisfied by the office. And designers pitched a suite of new furniture that promised to revolutionize their work. Unfortunately, it didn’t quite go according to plan.

Before the Cube

Historically, office workers were a small part of the workforce. And offices were smaller too, often with just a few clerks sitting in a small room with roll top desks and heavy wooden chairs. But then came the rise of multinational corporations, and paperwork, and typewriters, and iron frames for buildings, and elevators. Business became big business.

By 1960, office workers represented one-third of the American workforce. And they had moved into a new fleet of gleaming downtown skyscrapers. Offices were often arrayed with lower-tier workers clustered in the middle and managers enjoying privacy and windows around the periphery. These offices were loud, especially for the many workers without walls or doors.

Central shared space was cramped and noisy, but there was also a culture problem with respect to white collar work. The office was supposed to be a kinder, gentler workplace than being on a factory floor. But factory thinking was infecting white collar work, largely through a management strategy called Taylorism, an approach based on rigorous efficiency with little room for anything else.

The office of the 1950s was ripe for a shakeup, and that’s where Robert Propst came in. Propst was a freelance designer living in Colorado who would write to local businesses, like concrete suppliers or people who made playground equipment, and offer his services — and despite lacking expertise in those fields, he got a fair bit of work that way. In 1958, Propst went to the Aspen Design conference, where he met the president of the furniture company Herman Miller. Herman Miller was famous for its iconic Eames chairs and Noguchi tables, but the fancy furniture business wasn’t a huge growth industry. Herman Miller wanted to expand its offerings, though, and so they brought Propst out to Michigan and put him on the payroll so he could ideate about essentially whatever he wanted to.

At Herman Miller, Propst came up with a lot of wild ideas in various fields that were beyond the current scope of the company, including cattle branding and timber harvesting. Eventually, though, he settled on something that seems pretty obvious for a furniture company: office furniture. Why? Well, for one thing: he didn’t like his own.

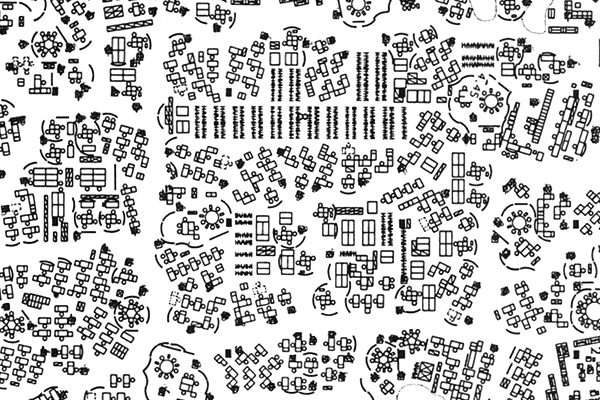

Around this time, the idea of “the knowledge worker” was becoming popular – the concept that many office workers weren’t all drones. Accountants and copywriters and engineers needed a new kind of workplace for creative thinking. In light of the German Bürolandschaft (or: “office landscape”) trend emerging across the Atlantic, he began to wonder if layouts could be more flexible.

Thus inspired, Propst teamed up with a mid-century furniture designer named George Nelson. And together, they devised a plan for the office of the future, one built around communication and movement. They called their new suite of furniture the Action Office.

The Action Office

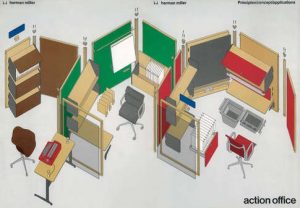

The Action Office was a suite of furniture that included a couple of stations for each worker. There was a coffee table, and a semi-enclosed phone booth, and a kind of book shelf, and a standing desk (which is pretty common now, but was unique at the time). All of it was made with high quality materials, like cast aluminum and rosewood.

This Action Office was designed around a couple of key ideas, including the notion that workers would be more productive if they were moving around rather than sitting still. Another principle was that a small amount of clutter was productive (versus filing everything away). Also, workers should have some privacy, but not too much — something in between a closed office and open floor plan.

In 1964, Robert Propst and George Nelson unveiled the Action Office to the public. They sold it as a new utopian vision of the workplace, complete with gorgeous high-end furniture and a layout that would make workers happier and more efficient. The Action Office wasn’t just a set of furniture — it was a way of life. But adoption was slow, in part because employers couldn’t bring themselves to splurge on expensive furniture for employees at the bottom of the corporate ladder. But Robert Propst wasn’t ready to give up on the idea. He went back to the drawing board, and rethought his entire approach. He returned four years later with his new and improved Action Office 2.

In 1964, Robert Propst and George Nelson unveiled the Action Office to the public. They sold it as a new utopian vision of the workplace, complete with gorgeous high-end furniture and a layout that would make workers happier and more efficient. The Action Office wasn’t just a set of furniture — it was a way of life. But adoption was slow, in part because employers couldn’t bring themselves to splurge on expensive furniture for employees at the bottom of the corporate ladder. But Robert Propst wasn’t ready to give up on the idea. He went back to the drawing board, and rethought his entire approach. He returned four years later with his new and improved Action Office 2.

Action Office 2

Like many sequels, Action Office 2 was less interesting than the first one. Instead of aluminum and solid hardwood, the new designs featured lots of plastics and laminates, which brought the price way down, but the beautiful mid-century modernist furniture design was gone, and along with it: the designer George Nelson. He and Propst had a falling out over their divergent visions.

Like many sequels, Action Office 2 was less interesting than the first one. Instead of aluminum and solid hardwood, the new designs featured lots of plastics and laminates, which brought the price way down, but the beautiful mid-century modernist furniture design was gone, and along with it: the designer George Nelson. He and Propst had a falling out over their divergent visions.

Without Nelson in the mix, the new furniture kit looked a lot more conventional. There wasn’t a phone booth or a coffee table. The standing desk became a normal height desk and the stool became a regular office chair. One other big change was the inclusion of fabric-covered room dividers that were modular and mobile. The idea was that these would be moved around a lot to reconfigure spaces, and Propst explicitly did not want them sitting at right angles creating cubes. Of course, that part of the vision went horribly wrong, and this creation became a kind of accidental prototype for the cubicle..

Cube Farms

The new Action Office was a hit, and Herman Miller sales went up by millions after it was introduced. This also spawned a series of knock-offs with fabric walls that were less mobile. The most efficient way to lay them out involved right angles, creating the kinds of enclosures Robert Propst never wanted. George Nelson, his former partner on the project, hated the trend, too.

The new Action Office was a hit, and Herman Miller sales went up by millions after it was introduced. This also spawned a series of knock-offs with fabric walls that were less mobile. The most efficient way to lay them out involved right angles, creating the kinds of enclosures Robert Propst never wanted. George Nelson, his former partner on the project, hated the trend, too.

The Action Office was supposed to solve the problems of the open, 1950s-style office, but it just created new problems. Now, instead of loud offices with no privacy, people were becoming enclosed and trapped inside these giant fabric walls, which got smaller and smaller over time. The depressing cubicle was a mirror of some other trends in the white collar workplace. The US went through a recession in the late 80s, and American businesses started “trimming the fat,” and “downsizing.” In other words: they fired lots of people.

The Action Office was supposed to solve the problems of the open, 1950s-style office, but it just created new problems. Now, instead of loud offices with no privacy, people were becoming enclosed and trapped inside these giant fabric walls, which got smaller and smaller over time. The depressing cubicle was a mirror of some other trends in the white collar workplace. The US went through a recession in the late 80s, and American businesses started “trimming the fat,” and “downsizing.” In other words: they fired lots of people.

Robert Propst lived long enough to see the rise of the cubicle. In 1997, he gave an interview to the New York Times, where he called the new wave of cubicles “monolithic insanity.” But he didn’t think his designs were the problem. In the interview, Propst defended his original designs. He offered these words of wisdom. “One of the dumbest things you can do is sit in one space and let the world pass you by.”

Opening Back Up

By the early 2000s, the cubicle was on the way out, replaced by the modern open plan, which was popular with Silicon Valley. Much like the 1950s, workers were arrayed together, sitting at long rows of connected desks, but this time around, the absence of fancy furniture became a point of pride. The spaces became less noisy, in part because the machinery isn’t as loud, and many workers wear headphones.

Silicon Valley pitched the modern open plan as a way to fuel collaboration — with everyone in close contact, liberated from the cubicle, people could work together more. But studies suggest the opposite may have happened, perhaps because it’s awkward talking in a big room, even if (or maybe especially when) it’s very quiet (and cramped). In 2010, offices had an average of 225 square feet per employee. By 2017, that number had dropped to 151, and it continues on an overall trajectory of decline.

The Future of Work

When the pandemic hit millions of people made a very abrupt transition to work-from-home. This raised a lot of questions about how much we need a physical office. Maybe the next era is a permanent shift to remote work, the total death of office space. But it is definitely too soon to say, and the reality is likely to be more nuanced.

Meanwhile, companies continue to experiment with various furniture and formats for office spaces, some of which seem unlikely to gain traction, like an inflatable wall system developed by Google. How people work, how well they work, and how much they enjoy it will likely depend (as it always has) on factors other than just interior design. No one chair or divider is going to fix larger office problems that require policy solutions. These remain useful but insufficient objects — employers need to step up with more fundamental approaches.

Comments (5)

Share

Hi, I’ve been enjoying the conversation on offices, but I’m slightly surprised no one has mentioned Ricardo Semler EO of Semco in Brazil. This conversation has been his soap box for decades, definitely worth looking into. It would be neat to hear what everyone thinks of his ideas of officeless work.

Your fan,

Mario

I enjoy the stories about offices. I profession has provided me the opportunity to search and learn around the world and working with business partners to provide innovative solutions for the work place. For the commercial or residential space. For over 30 days, I amazed with the power of the creativity and engineering. The common goal has always remain the same, provide humaity, peace … productivity will follow.

A suggestion, have you covered the “Shared Office”. Has changed in the last 5 to 10 years. Hospitality has taken it on over the last couple years.

When I was freelance Architectural Designer, found it most beneficial and a key to my success.

Sincerely,

Maurizio

I think the one guest is speaking around the inherent truth regarding power struggles of people being undervalued. She didn’t raise it, but it is worth mentioning (even if it is obvious to some). The professions she mentioned as being determined to have little control and are given disposable status are all comprised dominantly of female employees.

Great episode. Having worked in the Chicago Loop for 25 years at a multinational IT firm you managed to hit the key points. Directions to take for later stories…how does information security design drive flexibility in physical space? How can we use VR, XR, AR tech to encourage interaction and engagement rather than further isolate us. One of my favorite videos of future workspaces was the Future Product Vision posted by Microsoft in 2017(its the one with the scuba diver and ocean research scientist).

This article is the tip of the iceberg in the universe of office and workplace discussions. Right now it seems that many of the big tech companies will be asking for employees to return to the office. As an architect and designer of workplaces for many tech companies, for all of my career I have been a part of the full range of office layouts and amenities for the employees. It will continue to evolve, and I look forward to seeing how the work from home and “hybrid” office continues to change…