The first time that David Bohnett heard about the internet, he knew that this was going to be a technology that was about to change the world. Today, David is a philanthropist and tech entrepreneur, but back in the early 1990s he really wanted to get on the ground floor of this brand new medium. Bohnett and his business partner, a man named John Rezner, decided in order to be a part of this digital revolution they would found an internet company that hosted websites. The plan was straightforward enough: the pair would provide the online space and some basic tools so that individuals or companies could build their own webpage. And the company would host those pages on its servers.

They called their company Beverly Hills Internet, and Bohnett says that they were doing okay at first. They were starting to get some visitors to its website, but John and David found it difficult to get the kind of sustainable traffic that they really wanted… because of one huge early 90s problem: most people did not understand what the internet was.

“Nobody really understood at the time what it meant to create a worldwide web of these kinds of connections where all computers. were talking with one another and sharing information, explains Bohnett, “so I had the challenge both trying to explain to my friends what I was trying to do and the wider world at the same time.” It wasn’t that long ago that people had to make an enormous leap from a world with essentially no internet to trying to conceptualize what a globally connected computer network meant, or what they would even do with it. Before search engines like Google, or social networks, or apps, the web seemed like this confusing, nebulous blob of information. It was this strange, new technology that was hard to wrap our brains around.

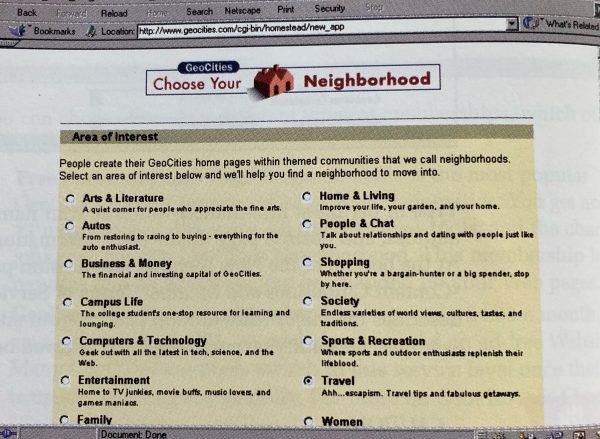

Because David ran an internet company, his business depended on users having some grasp of what the internet was. So it was his challenge to get people comfortable on the web. And one day in 1994, it just came to him. His hosting site didn’t need a technological innovation, it needed a conceptual one. Users needed a new way of navigating the web. So he sketched out a plan to make his website feel more like a real neighborhood. “You’d go to a two-dimensional representation of a neighborhood where you would see streets and blocks. You would see icons that represented houses […] and you would actually pick an address that you wanted to create your website. You had a sense that you were joining a neighborhood,” says David.

He didn’t want people to think of the web as a thing you logged onto, but more like a physical place to dwell in—like a house. Your new webpage was that house, in an online community of your choosing. This was all a new frontier, and you were in a way a virtual homesteader. David and his team were endowing users with a sense of digital manifest destiny one virtual neighborhood at a time. It was such a revolutionary idea that David and his partner decided to chuck out the whole “Beverly Hills Internet” name and change their company to something that fully leaned into the spatial metaphor they were creating. They called it GeoCities.

Digital Manifest Destiny

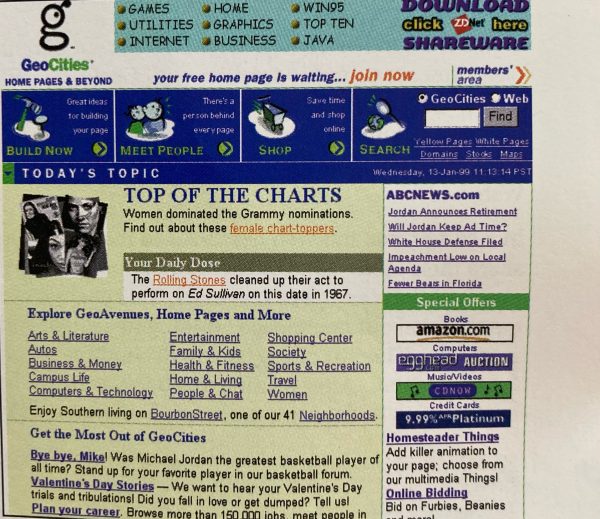

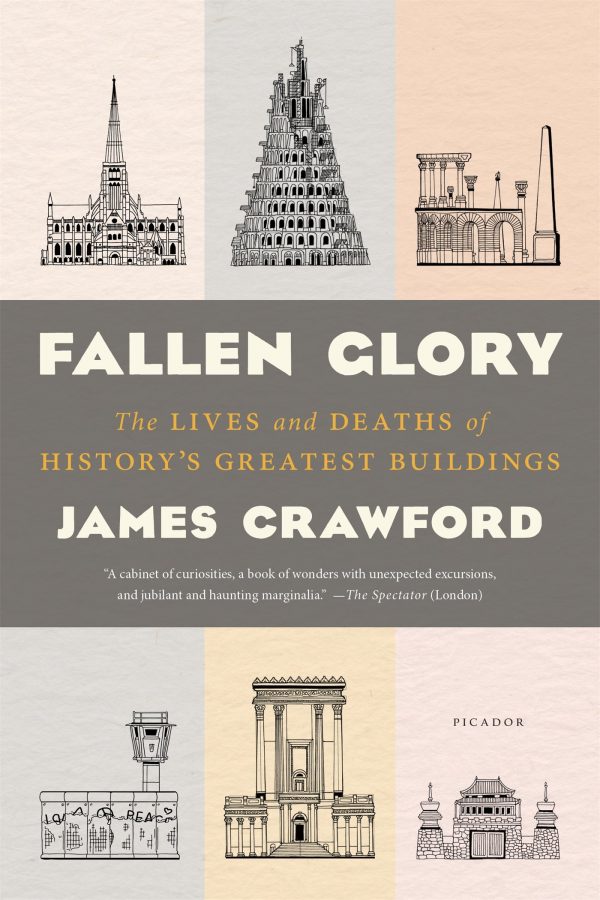

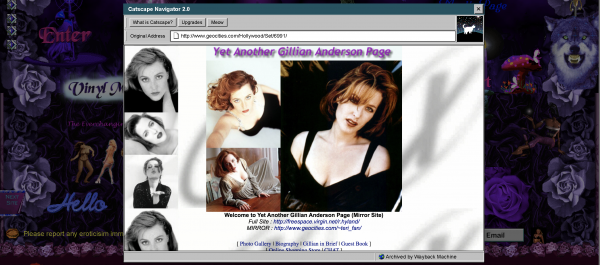

“The story of GeoCities is just a fantastic parallel for a real building—for something that was conceived of and created to model real life, but in the domain of cyberspace… and which ultimately had a catastrophic and dramatic fall in the end,” says James Crawford, author of Fallen Glory: The Lives and Deaths of History’s Greatest Buildings. “GeoCities was creating these communities and then conceptualizing them as places you could go as neighborhoods on the net. So you could be a citizen of a country, and you could then be a netizen of somewhere like Geocities.” The website was a collection of metropolises, each with their own neighborhoods built around shared interests. There was a region called Heartland where you could discuss tractor models or Pettsburgh where you could talk endlessly about your cats, or you could an endless amount of fan sites dedicated to Dana Scully in Area 51.

As soon as they established this spatialized version of the web, GeoCities really began to click for people. Bohnett wanted users who built their webpages in GeoCities to feel like part of a community. “I think a lot of that comes from my own experiences as a gay man and coming out and meeting other lesbian and gay people and understanding the power of meeting others of your own identity,” explains David.

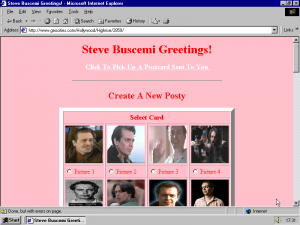

There were of course some limitations to user-generated content. The color palettes of most GeoCities pages seemed like they were chosen randomly, or maybe even chosen with the intention of making them illegible. like neon green text over a neon yellow background. The website was flooded with pages featuring “under construction” signs, low-res photos, strobing GIFs, and midi song files.

“There was an absolute obsession with comic sans font,” says Crawford, “all these things that almost feel like a kind of early vomitus of the Internet.” Looking back through the lens of the flat design and minimalism that came after, it’s hard to click through these pages without having a chuckle. It was much more chaotic, but the pages built on GeoCities reflected this amazing moment when people were attempting to figure out what the internet was, and what it could be.

Pop Goes the Bubble

By 1998, GeoCities was the third-most visited website on the internet, just after Yahoo! In fact, Yahoo was so impressed with GeoCities’s rapid ascent that they bought the company from David and John. Executives at Geocities believed that combining forces with Yahoo would put the website on steroids… but that wasn’t what most GeoCities users wanted. David says that a lot of users were concerned that GeoCities would lose its independence, which is exactly what happened. Six months later, GeoCities users woke up to a notice asking them to re-register, granting Yahoo the rights to all content on the website. Many users were upset by this and protested the terms of service and Yahoo eventually relented the terms, but this moment signaled the beginning of the end for the website.

It was the beginning of the end, not just for GeoCities, but for a ton of internet companies around the web. The dot-com bubble had been rapidly inflating throughout the late 90s because investors were pouring money into internet startups left and right, and just crossing their fingers that one day they’d be profitable. There was actually a mantra that you weren’t a successful dot-com company unless you were losing money. By the year 2001, the bubble had burst and corporations like Yahoo were losing their footing.

The internet was starting to change fast. Throughout the 1990s, a lot of users were working in a static, entry-level version of the internet. It was more homemade – identifiable by those vibrant personal pages hand-built by users. It’s where GeoCities had thrived. By the time the new millennium rolled around, the internet was evolving into a whole new experience. This internet was based around interactive social networking sites. You would punch in your name, age, and relationship status, and the site would spit out a manicured profile page. Users were encouraged to write on each others’ walls, and tag, and comment. GeoCities had created this great spatial metaphor to help people understand the web, but users were outgrowing that metaphor. Eventually, having a GeoCities account felt just plain embarrassing.

The Deleted City

Yahoo’s stock started to plummet shortly after it bought GeoCities, and year after year the site was losing more users. From a business perspective, GeoCities seemed like dead weight. In July of 2009 Yahoo announced that GeoCities would be closing and all files on the servers would be deleted. GeoCities was about to be completely wiped out as if it had never existed.

This was the wholesale destruction of a website that changed the way people looked at the internet. A lot of people believed that these pages deserved to be saved, but a handful of people decided to actually do something about it. In 2009 Jason Scott was a systems administrator who ran his own website that archived BBS documents. At the time, Scott was noticing more and more that old school hosting services like GeoCities were going dark and he couldn’t stop thinking about all of the user-generated content that was being destroyed in the process.

Scott wanted to make sure sites like GeoCities or their data weren’t just erased, so he wrote a post on his website lamenting the loss of websites that hosted user-generated content. Scott ended up connecting with a group of like-minded digital preservation enthusiasts scattered around the world, and they drafted a plan. They called themselves Archive Team and decided it was their mission to save the internet’s digital heritage by archiving as much as they could. “We announced that we are Archive Team,” explains Scott, “We’re going to rescue your s***. And that was our slogan. We’re going to rescue your s***.” And they started with GeoCities.

Archive Team had a dual mission: in addition to preserving things, they also want us to understand that digital information is fragile. The profiles you build on any social media site, the videos you upload to Youtube—they all exist out of your hands and on some corporation’s servers and can vanish at any given moment. “They have no idea that it can literally disappear in a week or a day,” says Scott, “There’s an error and it’s gone. And I get to see that over and over and over again.”

Yahoo! had hinted in early 2009 that it was closing down the service sometime later that year, so GeoCities could have maybe a few months or a few days. Archive Team got to work immediately trying to recruit as many people as possible to help with what Jason’s referred to as GeoCities-download-a-palooza. They had their computers crawling Yahoo’s servers to pull out any piece of public GeoCities data they could get.

Then, on October 26th, 2009 after six months of work, the day they all dreaded finally came. Archive Team watched from their respective computers as the digital city slowly went offline for good. Jason said that watching Yahoo pull the plug was like something out of 2001: A Space Odyssey. “They’ve now powered down this server. They’ve now powered down this server. And they’re still grabbing as fast as they can from the other servers […] until finally it’s just not responding meaningfully at all.”

Second Life

But it wasn’t all for nothing. In the end, Archive Team managed to extract a terabyte of data from GeoCities, and as it turns out, there were multiple parallel projects that were downloading GeoCities data. A lot of them have sent their data to Jason for safekeeping. Altogether, Archive Team saved more than a million accounts from deletion. Archive Team wanted to bring some attention to their work. So they took all of the GeoCities data they’d preserved and turned it into a torrent on The Pirate Bay.

Jason wasn’t sure what people would eventually do with that GeoCities data, but that wasn’t really his concern. He just wanted to make sure it was safe and available to anyone who wanted it and if he was lucky, something useful would come out of it down the line. Actually, a number of people have downloaded the GeoCities torrent and have made some cool projects with that data. A good amount of Geocities pages have been restored and you can browse through them online. Since saving GeoCities, Jason and Archive Team have preserved a number of dying websites around the internet from Yahoo! Groups to Justin dot TV. It’s all accessible on a digital archive called Wayback Machine where you can find over 477 billion saved web pages. Wayback Machine was founded by the Internet Archive where Jason Scott is now an archivist.

If the internet’s history were sketched to look like The March of Progress (that famous illustration charting human evolution with an ape on one side and a man on the other) GeoCities would be like that third guy from the right. A little hairy, and a little clumsy… but definitely an important link that made us what we are today.

“I mean, it’s not necessarily art, but it’s absolutely culture,” says Crawford. “You know, this is what we’ve always done as humans. You know, going back to the earliest marks we put on the caves as you’re presented with a surface. And what do you do with it? How do you mark it? How do you represent who you are on that space? [A] number of people have made this comparison between the kind of cave paintings of Lascaux. [And] it seems like a bizarre, almost absurd comparison to make, [but] that’s absolutely what it was. It was people grappling with new technology and how to represent their humanity in that space.”

Check out Olia Lialina and Dragan Espenschied’s One Terabyte of the Kilobyte Age project here. Also, check out cameronsworld.net and The Deleted City if you’re interested in seeing more cool projects created with GeoCities data.

Comments (7)

Share

On good thing about all that comic-sans is that it brought sans (without) into use again. I just told my phisiotherapist I got out of bed in the morning sans-stumble. ❤️

I sort of miss the days of ugly old webpages and feeling like we were sharing for free without fear.

So… does this mean that there might be a backup of my old Geocities site somewhere? How would I find it? It was in the Athens Academy….

Well, not to try to look smart, but I found that 2D spatial analogy really pointless, forced and limiting. I went there in spite of that, not for that. Oh, and because it was free. It was just about the only OK free hosting option for our random garbage at the time.

My brother had a website and I remember him showing it to me in like 1998. It didn’t really say anything much but I recalled him being so jazzed that when it (finally) loaded up, it played House of Fun by Madness (Roman knows the song for sure). I actually could not tell it was that song because it was 1998 and music on websites sounded terrible.

Anyway, he was so proud.

Save for the Barney the Dinosaur protest webpage, I recall the internet being a far kinder and certainly more forgiving place than it is today.

Thank you again 99% PI for adding a sliver of positivity back.

Is there any consideration about what is now considered private personal data existing in these archives and being shared via the archives? With current technology I’d imagine it would be quite easy to extract email addresses, dates of birth and other forms of identification and potentially use it for online fraud. Back in the day people were not so savvy about keeping this information safe.

Great episode, but I just don’t understand why it isn’t called ‘Jason and the Archonauts’.

Hit up theoldnet.com! It has a bunch of geocities pages indexed!