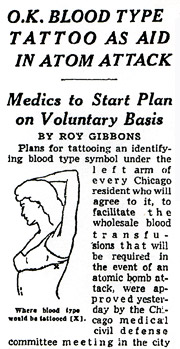

In the early 1950s, teenage students in Lake County, Indiana, got up from their desks, marched down the halls and lined up at stations. There, fingers were pricked, blood was tested and the teenagers were sent on to the library, where they waited to get a special tattoo. Each one was in the same place on the torso, just under the left arm, and spelled out the blood type of the student.

This experimental program was called Operation Tat-Type. It was administered by the county and the idea was simple: to make it easier to transfuse blood after an atomic bomb. At the age of 16, producer Liza Yeager’s grandmother, who went to school in Lake County, was permanently marked in anticipation of a nuclear catastrophe.

This experimental program was called Operation Tat-Type. It was administered by the county and the idea was simple: to make it easier to transfuse blood after an atomic bomb. At the age of 16, producer Liza Yeager’s grandmother, who went to school in Lake County, was permanently marked in anticipation of a nuclear catastrophe.

In 1952, the Cold War was in full swing and the government was busy developing civil defense strategies — things ordinary citizens could to do to help protect the homefront. In this case, the thinking was that if Russia attacked, the tattoos would make for quicker transfusions. They called it a “walking blood bank” — no need for cold storage.

It sounds morbid in hindsight, but many kids at the time took it in stride. It was just another manifestation of the concept of survivability. The idea that with enough canned food, shelters, fearlessness (and maybe tattoos) the American people would be able to survive an atomic attack.

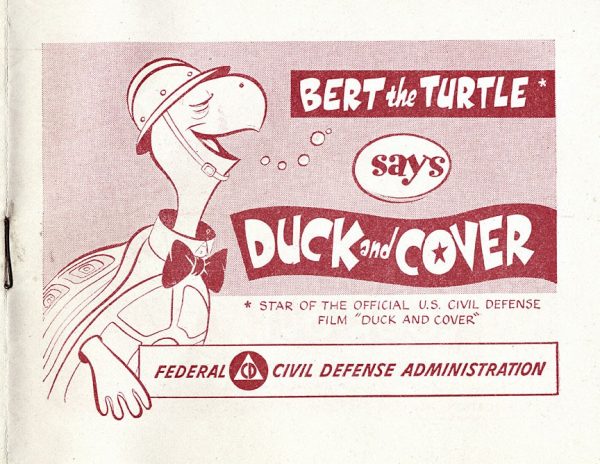

Duck and Cover

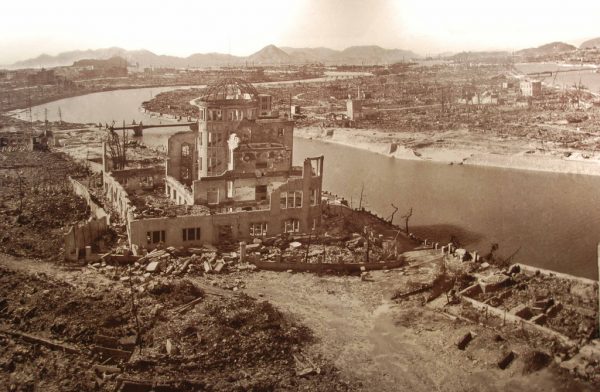

The idea of “duck and cover” gets made fun of these days. It’s considered the number one example of the kind of Cold War-era propaganda that seems totally ridiculous now — kitschy and absurd and unimaginably naive. But, in fact, the films and posters about ducking and covering were based on actual research of survivors at Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

In September 1945, just one month after the bombings of Japan, the US military sent a team of American doctors and geneticists to Japan to interview people who’d survived the attacks, looking to understand both the short and long term effects of radiation. That program would eventually be named the Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission (ABCC).

This program would also prove to be highly controversial, because the researchers who arrived in Japan weren’t there to treat the survivors, but only to study them. It was American lives — not Japanese — they were hoping to save. They wanted to understand who would survive and who would not if or when an American city was hit with an atomic bomb.

The researchers looked into things like cancer rates, irregular pregnancies and heart disease, but they also asked every survivor the same thing: where were you at the moment of detonation?

Before the ABCC researchers arrived, the physicists who had developed the bomb had assumed that they wouldn’t be finding survivors anywhere close to ground zero (or: hypocenter). Yet within just a few blocks of the hypocenter people who had been in the basement of a large concrete building had survived. And further out, researchers discovered that people who had taken cover (even momentarily) survived and actually seemed healthy. According to one account, a group of children who were diving off a cliff into a lake all got sick, except for the one who happened to be underwater. People who stood behind trees were also more likely to live longer. There were various sources of radiation to be avoided, but what mattered most was being shielded at the moment of the blast. And during the blastwave that followed, it was the people who were standing up who were most likely to be killed by shattering windows and falling debris. People who had been lying down when the blast wave hit, much more often … survived. The lesson seemed clear: in the event of an atomic bomb, if you could stay low and stay shielded (ducked and covered) you could be OK.

Even as the ABCC was publishing its findings, researchers had already begun studying things like psychology, group dynamics and infrastructure to see how society as a whole might hold up under a nuclear attack. The civil defense policies that emerged from this research all stressed that America could survive, but only if everyone — not just the authorities but everyday citizens — did their part. This meant doing things like protecting one’s home, doing air raid drills, dealing with irradiated soil and perhaps getting a blood type tattoo.

But even as children were learning to duck and cover, and farmers were learning how to protect livestock from fallout, though, the very idea of what a nuclear war might look like was changing.

Outgrowing Survivability

Just two years before Operation Tat Type, the Soviet Union had a grand total of five nuclear warheads. By 1960, they would have over 1,600. Many of these were thermonuclear weapons — hydrogen bombs exponentially more powerful than the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The idea that people and infrastructure might survive in the event of a nuclear war was growing increasingly dubious.

Just two years before Operation Tat Type, the Soviet Union had a grand total of five nuclear warheads. By 1960, they would have over 1,600. Many of these were thermonuclear weapons — hydrogen bombs exponentially more powerful than the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The idea that people and infrastructure might survive in the event of a nuclear war was growing increasingly dubious.

Still, government agencies like the Civil Defense Administration continued to promote the idea that the country could survive a full nuclear attack, in part because the gospel of survivability — however imaginary — still served other functions, pacifying the populace in the face of what seemed like an inevitable nuclear conflict. And to some extent, it worked — people believed they might survive.

Operation Tat-Type didn’t go far outside Lake County. Despite all the survivability fervor, it never made it beyond the pilot program. Today, the legacy of survivability is hidden behind a new series of titles, acronyms and other obfuscating symbols. The Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission, which studied the effects of the atomic bomb in Hiroshima, eventually became the Radiation Effects Research Foundation, a joint American/Japanese venture that has continued to study the long term effects on the survivors of the bomb and their children for nearly 75 years. The Federal Civil Defense Administration was combined with various other agencies to form FEMA in 1978. Its strategies have been adapted to deal with hurricanes and earthquakes in addition to possible nuclear attacks. And then there’s the tiny legacy of survivability inked on the torso of Carol Fischler — a faded tattoo that says “O positive” — just under her left arm.

Comments (19)

Share

In the epilogue you talked about the movie WarGames and the game Global Thermonuclear War. You mentioned the website NUKEMAP as a good game to represent it. There is another game called DEFCON that is a more “gamey” version of the same concept. Check it out!

Thought exactly the same thing :-)

“Duck and Cover” drills continued into the 60s, at least; I remember doing them in 1965 or so. But that might have been at least partially because I was in Alexandria, VA at the time – close proximity to Washington, DC. We moved the next year and I don’t remember doing the drills again, and it’s hard to say if the program ended or it was a regional thing.

These types of tattoos in fact live on, at least in the US Marine Corps. They are called “meat tags” and are in the exact same location. Left side of the torso. While they have more information than just a blood type, it’s the same general idea.

While they are not mandatory, it’s not uncommon… I have one as do many others. There has always been speculation on when the tradition might have started, and no one really ever seemed to know. Maybe this was the genesis.

Read the book Raven Rock. All of the Civil Defense stuff was propaganda, because that’s all CD could afford. The money was spent on continuity of government, not American citizen survivability. And this spending disparity continues even today.

I believe Franklin County, Idaho, was the (only) other location that did the blood-type tattoos. My grandmother would show us her tattoo.

Science doesn’t really support the nuclear extinction theory. No doubt many would die from a nuclear war, but hundreds of war heads have been tested on earth’s surface and clearly were all here to tell about it — among many other reasons.

NUKEMAP is awesome!

For a nice style termonuclear war videogame experience, take a look at a game called “Defcon (everybody dies)”

You can play the game of thermonuclear war as a computer game.

And it’s actually amazingly thrilling and macabre.

The world and your killstats all in glorious flowing scope visuals.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/DEFCON_(video_game)

Very interesting episode, I definitely liked the story.

The only question I have is why do you call Soviet Union as Russia? Was it on purpose?

The cold war was scary at times. In 1985 I was driving with my months old daughter when the emergency broadcast tone came on my radio and the papermill lunch whistle sounded, which was also the air raid siren. We lived equally near a Strategic Air Command Air Force Base and the Idaho backcountry. I seriously considered which way to go. Towards the SAC base and die in the blast or the Idaho backcountry and try to survive. It was terrifying. Then the radio went on to say it was a “only a test…”

“Duck and Cover” is still good advice! If you see a flash in the sky, get down and away from windows…it means something big exploded, and effects are on the way. Several teachers in Chelyabinsk, Russia saw the flash of the meteor exploding, remembered their training and yelled to their students to get under their desks….seconds before the shock wave blew the windows out

I always love 99pi episodes, but this one was closer to home than usual. It stopped me mid-jog. My grandfather (Sgt. John Archambault) was a chemist on that first medical team to travel to the bomb sites in Japan, the beginning of that commission that eventually dreamed up ‘duck and cover.’ John died years before I was born, but I have always been curious about what his experience must have been. There is a very dated but still interesting account of that early mission in the Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine from 1965 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2591311/). (Beware, troubling images)

Architects / Designers / Planners for Social Responsibility (ADPSR) was founded in 1981 as a response to threat of thermonuclear war. ADPSR spoke out for the design professions expressing the view widespread throughout the country and the world (but largely missing from the story) that the appropriate response to the threat of nuclear weapons (especially, but not exclusively, the larger thermonuclear weapons) was disarmament, a ban on nuclear weapons, and a redirection of war-planning and war funding towards socially responsible development. In fact, one of ADPSR’s earliest documents was a poster of monuments of world architectural history silhouetted in front of a mushroom cloud.

As the threat of nuclear weapons turned into the global annihilation promised by H-bombs (as in the movie Wargames, also featured in the story), U.S. authorities promoted civil defense in a way that can only be considered domestic propaganda — trying to convince Americans that we could fight and win a nuclear exchange with the Soviet Union in order to bolster support for belligerent Cold War policies and a bloated military industrial complex, including enough H-bombs to destroy the world hundreds of times over.

We at ADPSR are generally big fans of 99 PI, but feel that this episode ignored much important history from the Cold War Era. To see some of our history, check out: https://www.adpsr.org/blog/2019/1/26/nuclear-nightmares-with-99-percent-invisible

Your comment expresses my thoughts exactly. I thought this episode approached a degree of stubborn perversity in its seeming conscious refusal to consider that the best way to avoid the catastrophe of even the smallest nuclear attack is to get rid of all nuclear weapons. We see the results of this attitude expressed across the world when countries such as Iran attempt, quite legitimately, to develop the weapons that their self-declared opponents such as Israel possess with the support of the USA, the nation with vastly more nuclear killing power than the rest of the planet combined. Yet, somehow, Iran is seen by the media and your president as a threat.

Even Reagan had the sense to reduce nuclear weapons stocks in conjunction with the USSR. It’s time that the USA resumed good faith negotiations. This episode was disgracefully irresponsible in failing to give even one sentence of acknowledgement of the need to disarm.

I learned “Duck & Cover” in elementary school in the mid-seventies as a strategy to survive earthquakes, and had no idea that it went back to the early cold war until I saw some of those old films.

This episode reminded me of my edition of the “Joy of Cooking” cookbook.

The section “About Water” has a section on water purification, which reads: “If water has been exposed to radioactive fallout, do not use it. Water from wells and springs, if protected from surface contamination, should be safe from this hazard.” It then goes on to explain how to properly treat and store water in your bomb shelter.

https://books.google.com/books?id=C4_5MCUd6ucC&pg=PA520&lpg=PA520

Imagine my surprise to find out that the blood type tattoos go at least as far back as all members of the waffen ss in nazi Germany. I love and donate to 99PI, but I think that bit should also have been in the story.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SS_blood_group_tattoo