In January, reporter Rebecca Kanthor set out to travel across central China from her home base in Shanghai, making her way to her in-laws home for Chinese New Year. As she walked out the door and put a location into her GPS app on her phone in a robotic voice instructing her to “Please wear a mask if you’re going out. Be safe.”

A week later when she returned home to Shanghai, the change was even more drastic. Anyone who ventured outside was wearing a mask. There were public service posters all over reminding people to wear masks. Face masks seem like such an obvious response in the face of an epidemic but are more commonly worn in China and other countries in East Asia than in the West. Around the world, there’s no doubt that this simple innovation has saved countless lives.

The Great Manchurian Plague

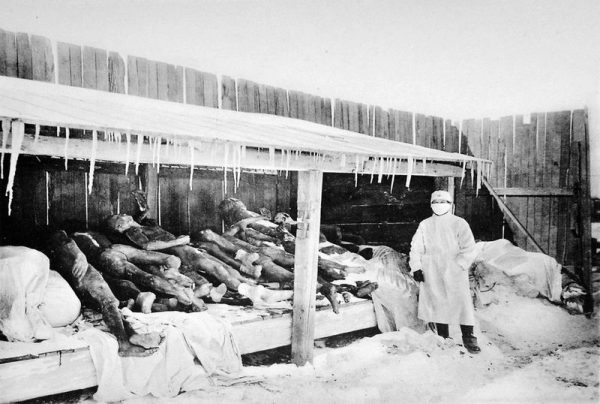

Over 100 years ago, China was the scene of another devastating epidemic called the Manchurian Plague of 1910. Back then, Manchuria was a contested territory—Russia, China, and Japan all claimed it was theirs and even called it the “cockpit of Asia.” But in 1910 this contested territory became the site of an incredibly deadly outbreak of plague. The mortality rate was so high that 95% or more of those that were infected died within just a few days of contracting it.

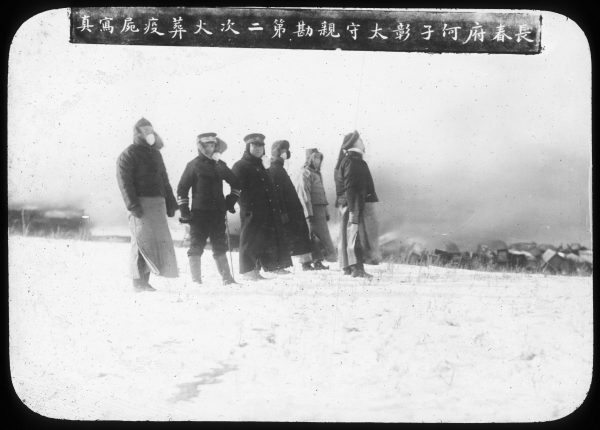

Christos Lynteris is a medical anthropologist at the University of St. Andrews in the UK. He says that at the time photos of that outbreak in Manchuria were seen in newspapers around the world. “Photography played a key role in establishing this idea of a global outbreak, an outbreak which is spreading across the globe,” explains Lynteris. Masks had been used in a clinical setting as early as 1897, but not systematically by the general public during an epidemic.

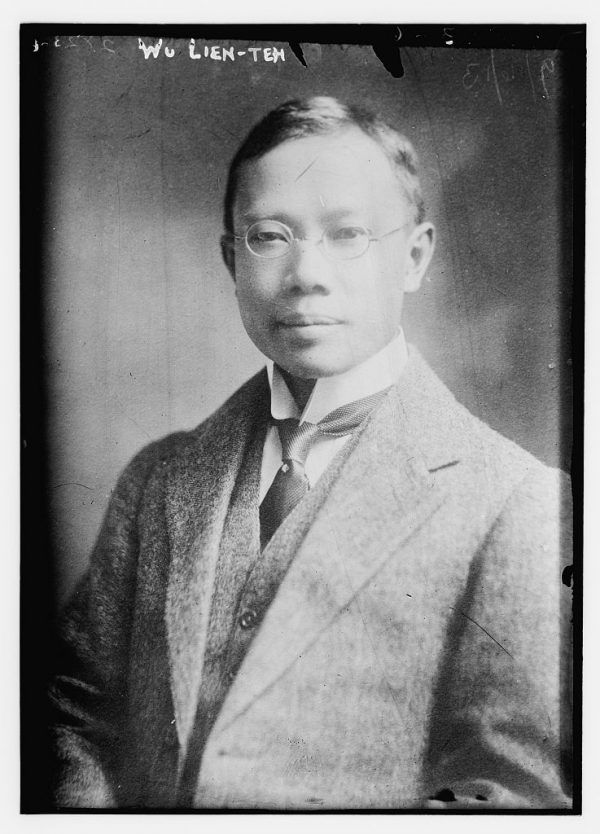

That all changed in Manchuria because of a doctor named Wu Lien-teh. Wu was a young Chinese-Malaysian doctor who had gone abroad to study medicine in Europe, in Germany, and France and the UK. The Qing Dynasty government called him in to lead the Chinese efforts against the plague, and he was immediately greeted with disdain from his Russian, Japanese, British, and French counterparts in the medical field. But he was a brilliant scientist and quickly deduced that this disease was a pneumonic plague, meaning it was airborne and spread through droplets in the air. At the time, most of the experts thought the plague was being spread by rats. Wu Lien-teh became convinced that the plague bacteria was spreading through the air, which he was right about. Based on that theory he made a fairly simple suggestion that people should start covering their mouth and nose with face masks.

Wu believed that all of his medical staff, as well as the general public, should wear masks, but other doctors wouldn’t listen to him possibly because of his young age and race. One French doctor named Gérald Mesny openly antagonized him and refused to wear his mask. Soon after, Mesny caught the plague and died vindicating Wu’s theory. After Mesny’s death, everyone began wearing Wu’s mask. People began photographing it and it became a symbol of medical success and the plague ended after 7 months. The government implemented a lot of epidemic practices that we still see today—wearing masks, quarantining patients, and cutting off travel to limit exposure.

The 1918 Influenza

Eight years later, when the 1918 Flu Epidemic hit, people remembered Wu’s mask and it started to be seen and adopted across the world. The acceptance of wearing masks really varied depending on where you were during the time, but it wasn’t a widespread practice.

After the pandemic ended in 1920, wearing masks fell into obscurity in the US mostly because the country did not experience many deadly epidemics, but in China, there was never an opportunity to forget. As Lynteris explains, “In China, you have a continuity of the use of the mask. So the mask story does not end in 1911 or 1918. It continues through several other outbreaks in the 20s, in the 30s. And then in Mao’s China after 1949.” Not only that, but the medical mask also plays an important role in public health campaigns and in propaganda.

A lot of people would say that wearing a mask is a “cultural” thing in China which is true in a way, but Vivian Huang, a historian at the Shanghai Library, says that they only became “normal” in China because they were required by the state. Wearing masks was promoted through propaganda posters, in the newspapers, and various other public health campaigns. She says that the adoption of masks was actually a slow process that needed to be learned.

The New Normal

By the time the SARS epidemic hit China in 2003, the face mask had become pretty common, and people by this point already knew what to do. Huang says it really has taken Chinese people 100 years to get to the point of acceptance of wearing masks during an infectious disease outbreak and now to the point when people just wear it when they’ve got a cold to protect others. It’s normal practice whether you need to wear them during polluted days, or to keep warm. In the East, one wouldn’t feel like others would discriminate against them for choosing to wear a mask… but that has been a different story in the US. Many Asian Americans worry about wearing masks because the culture is so different in the United States.

Lynteris thinks there’s something else going on in the West because masks are seen as racialized and associated with China, which leads to xenophobic behavior. ‘You have this phenomenon [that] some journalists call ‘mask-ophobia,'” which is basically an attribute of sinophobia […] people who look Chinese or who look Asian being attacked on the streets of London […] because they’re wearing masks.” Lynteris says this kind of insidious racism isn’t even recognized by most people.

But Huang and Lynteris say that it’s the very opposite in China. A mask is a welcome sight because people feel it shows that the person wearing the mask cares about others.

Wearing a mask is an act of protecting yourself, but more importantly, protecting the people around you. It provides a sense of solidarity—that we’re all in this together.

99% Invisible’s Impact Design coverage is supported by Autodesk. Autodesk enables the design and creation of innovative solutions to the world’s most pressing social and environmental challenges.

As a leader in design software, Autodesk has introduced new programs to assist its customers, communities and employees impacted by COVID-19. To address the shortage of personal protective equipment (PPE), Autodesk is helping connect design and manufacturing resources to develop new solutions for PPE and life-saving devices. Resources include open source design files, design review and validation tools, and a platform to connect designers with companies around the globe with manufacturing capacity to help with production. Learn more about these efforts on Autodesk Redshift, a site that tells stories about the future of making things across architecture, engineering, infrastructure, construction and manufacturing.

Correction: The Manchurian Plague was incorrectly referred to as a virus in one instance of the podcast. The plague is a bacteria, not a virus.

Comments (6)

Share

When I first came to Japan in the mid-90s, I was surprised by the number of people wearing masks. Not wanting to get others sick is one of the primary reasons they are worn. But a second important reason is allergies. Tons of folks in Japan are allergic to tree pollen (there’s a story in there about how millions of trees were planted around Tokyo post WWII to get people working and how it has backfired tremendously now that those trees are mature and pollinating like crazy, but I digress) and wear masks throughout the spring because they are absolutely miserable. Anyhow, thought you might appreciate one more reasons why masks are so common in this corner of the globe.

Two words: air pollution. That’s the only reason why everyone had masks when this thing started. Ppl had masks prepared and wore them on the days when it’s really bad.

Interesting article with embedded photos ends with a faceful of advertisement about autodesk in the same formatting after an embedded image so you automatically read the ad too. Smooth, guys, real smooth. Well done making me regret reading the rest of the article.

In quite a few countries, wearing surgical masks would be illegal to some extent (because you cannot be covering your face in public). Luxembourg – where I live – is one such place.

cf. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anti-mask_law

Lux’g government has made it compulsory to wear mask in public now.

I’m a little surprised that pollution was mentioned super briefly, just one time in a minor sentence I think.

People in Asia wear masks because of air pollution. I do understand that plagues made it more popular, but the fact that everyone has masks all the time was because of air pollution. Go to any Asia country, especially East Asia and you will see everyone wearing fabric masks when they do outside. There were even a fashion industry around the masks just because it’s such an essential everyday that people want to look good in them. It’s only during plagues that people wear medical masks. It’s not by chance that when the Covid-19 crisis started, medical masks were all bought up, it’s not because people in Asia don’t have a fabric masks, which they uses everyday, but because they would prefer to have a medical mask to protect themselves. If masks are popular only because of medical reasons, the fabric masks would not have been such a huge industry.

Another point is people wear masks to protect themselves. It’s still good for the public, but let’s look at it from a real perspective. It’s very easy to see people wearing masks and then open them to sneeze, or try to get the best medical masks available, as to filter the virus from the air.

I read recently how during the Spanish Flu Pandemic, there was an anti-masking league that met at least once in San Francisco. What that article didn’t talk about was the racialized associations with masks, and how the anti-masking league thus also had enormous racist subtext.

This also reminds me of a recent episode of “What Trump Can Teach Us About Con Law”: San Francisco created explicitly racist quarantines around the businesses and homes of Chinese residents of Chinatown (but not the white businesses in the same neighborhood) in response to an outbreak of plague in 1904, but the Supreme Court ruled that particular quarantine to be unconstitutional (while maintaining that states and municipalities have legitimate power to enforce quarantines on a legitimate medical basis). https://trumpconlaw.com/39-quarantine-powers