Journalist Sam Bloch used to live in Los Angeles. And while lots of people move to LA for the sun and the hot temperatures, Bloch noticed a real dark side to this idyllic weather: in many neighborhoods of the city, there’s almost no shade. He was surprised to find people awkwardly huddled behind telephone poles to get relief from the glaring sunlight. “I noticed people waiting behind the people waiting behind telephone poles because there’s only that small sliver of shade,” says Bloch.

Shade can literally be a matter of life and death. Los Angeles, like most cities around the world, is heating up. And in dry, arid environments like LA, shade is perhaps the most important factor influencing human comfort, “even more than our temperature, more than humidity, more than wind speed,” says Bloch. Without shade, the chance of mortality, illness, and heatstroke can go way up. People become dizzy, disoriented, confused, lethargic, and dehydrated — and for the elderly or people with health issues, that can tip into more dangerous territory, like heart attacks or organ failure. Shade can literally save lives.

Public Shelter

There are lots of factors working against shade coverage in Los Angeles. The biggest might be the city’s lack of consistent tree canopy. From outer space, it’s clear that LA has a big tree disparity, with many green neighborhoods, and many completely exposed to the sun.

Los Angeles is also notoriously anti-density. “Sunlight and open space is a part of the culture, but it becomes a problem for people who can’t escape it,” says Bloch. There are relatively few tall buildings and they’re spaced far apart from one another or located in certain height districts—Downtown LA being one of them, leaving other parts of LA without the shade that tall buildings provide.

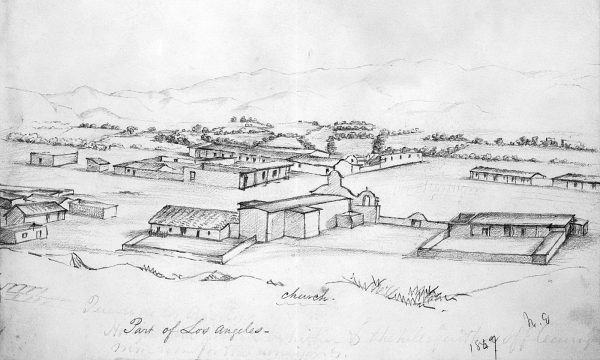

Los Angeles wasn’t always like this. If you look at photos of LA from 150 years ago, it’s mostly grasslands. When LA was settled by the Spanish, the city’s design was governed by a rule called the Law of the Indies, which meant the city’s layout roughly conformed to a 45-degree angle, ensuring sunlight in the winter and shade in the summer.

The influence of Spanish architecture meant that early development in Los Angeles included a lot of missions and adobes with internal courtyards that are shaded, and covered walkways, or paseos, which provided relief from the sun before air conditioning.

Hot Dam

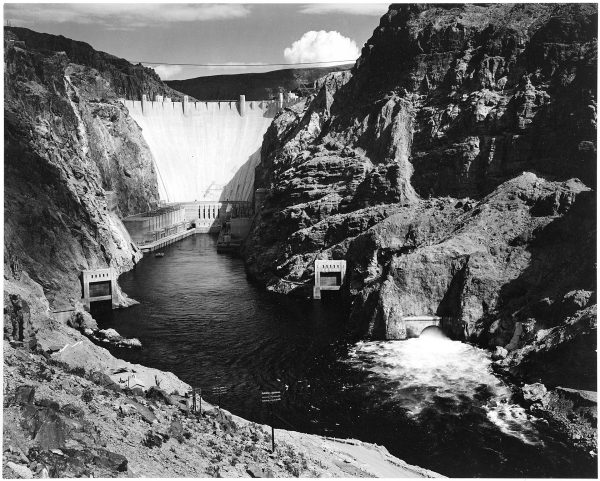

But things changed drastically in LA after the advent of cheap electricity and the completion of the Hoover Dam. The city rebuilt itself around controlled air conditioning and car culture. Palm trees became an LA calling card. “As Mary Pickford said, [palm trees are] very good for window shopping from the seat of your car because the tree trunks aren’t that robust,” notes Bloch, but they’re also “as one essayist said, about as useful for shade as a telephone pole.”

Wealth of Shade

Today, in Los Angeles, shade is distributed to people who can afford it. If you go into neighborhoods that were designed to be wealthy residential enclaves, the sidewalks are wider and include strips of grass four to ten feet wide, for the easy planting of thick, leafy trees.

Hancock Park, for example, is a flat neighborhood, landlocked in the center of the city. There is nothing about it that naturally lends itself over to being a lush, verdant tree canopy. But the neighborhood was developed as an exclusive, wealthy residential enclave. And when that happened, the power lines were moved underground and the layout was designed specifically to allow for tree growth. This is not the case for other large residential areas across Los Angeles.

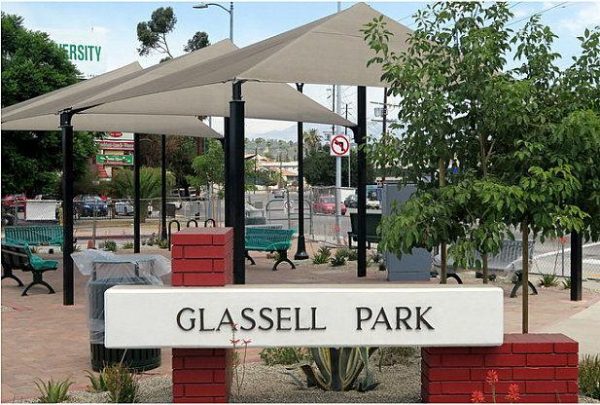

There have been efforts to add more shade, especially around bus shelters, but it’s been difficult, says Bloch, “because shade is a tripwire.” In the instance of the Glassell Park Transit Island, a concerned neighborhood resident wanted to put up a simple bus shelter over a space where she saw people congregating. She ended up working with an architect to erect shade sails at the transit island. This seemingly easy development became very complicated. The new structure had to be consistent with the regulations of the Americans with Disabilities Act which meant adding curb cuts to make the sidewalk wheelchair accessible. It also meant expensive changes to underground water-mains and power lines. “You have to take care of all these other things before you can decide to do this very lightweight sort of low-res fix,” notes Bloch.

Perishing Shade

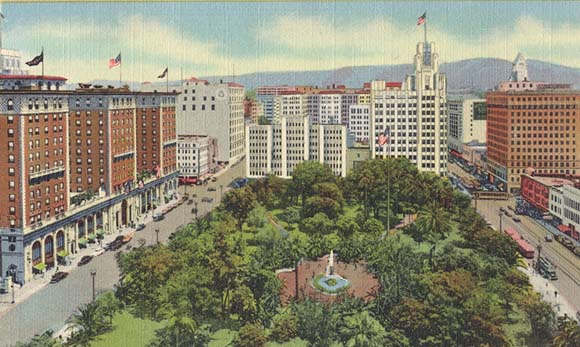

But the sidewalk isn’t the only place where LA has a shade problem. The public parks also provide very little refuge from the hot sun. Pershing Square, for example, used to be full of shade trees. But after a new underground parking structure destroyed the root system, the thick, dense tree canopy was replaced. Other parks lack trees because of a strategy Bloch has reported on called crime prevention through environmental design. In LA, there is an idea that increased visibility in public spaces will lead to higher levels of public safety. In several instances, it’s believed the LAPD has installed pole cameras in parks or in public housing projects and cut down mature trees to give the camera a clear sightline.

Informal Shade

There have been a number of informal interventions to create shade across the city, particularly in Latino neighborhoods. James Rojas is an urbanist who writes about Latino urbanism, and leads a walking tour around Los Angeles where he makes note of tarps and DIY shade sails that have been connected between garages or hung up in alleyways to provide some public shade. These types of interventions are tolerated in private spaces, but as soon as they step into the public sidewalk, things become more complicated. Los Angeles processes 16,000 charges every year for obstructions of public space, a major deterrent to grassroots urbanism.

This episode includes an interview with Sam Bloch, about his article Shade which originally appeared in Places Journal.

Comments (20)

Share

Fascinating as always, but surprising you don’t look around the world to see how other cities address the problem. MITs treepedia project shows just how bad LA scores for trees. I live in Singapore, which is more humid than LA and the government here is very aware of the heat island effect ( which I don’t think you mentioned). We have trees everywhere and also a lot of covered walkways to shade people from sun and equatorial rain. We also have underground parking everywhere – surely LA can figure it out, if it wants to.

I wish there were more pictures in these posts. I tap on the link in the podcast show notes every time I listen to a 99PI episode and often wonder why there aren’t 5 times as many pictures to show me visually what I’m listening to an audio description of during the episode.

If you’re referring to the discussion at the end, please see the link at the end of the companion for images and analysis of “treescrapers” in urban environments!

The removal of trees in order to increase surveillance visibility for policing completely goes against research that indicates increasing green spaces in poor urban neighborhoods reduces crime in the area by 9%. I learned this listening to an interview with social scientist Frances E. (Ming) Kuo a couple of years ago on another program, “Hidden Brain”. The research, “Environment and Crime in the Inner City:

Does Vegetation Reduce Crime? is co-authored with William C Sullivan (both from U. Ill. Urbana-Champaign) and linked to the HB episode “Our Better Nature” from Sept. 2018. Maybe no one has told the LAPD and all the other stakeholders in LA that greening is a better way to reduce crime in the first place, and cool the city at the same time?

Great episode, as always, but I disagree with most of the second half of it.

If you would live in Europe, or understand European, or especially Italian cities better then you would know that Italian streets are normally quite narrow, in fact they can be very narrow, which makes them shadier, but also means that there is simply less room for trees.

Its true that the Bosco Verticale building in Milan is hardly an architectural masterpiece, but it takes a very simple idea, and makes it happen in a very effective way.

The argument that the carbon footprint of making the building stronger to hold the trees is greater than the offset the trees themselves give is short term thinking and it only makes sense if looked at from an american perspective where old is measured in decades, not in centuries. Think about how this building will look ten, 30 or 50 years from now. Think about the developement of the building’s facades over time, I expect it will be beautiful.

Finally, what about Hundertwasser? He was doing this 40 years ago, and the unfortunate result was not that anybody of consequence. ie. austrian city planners, listened to him, but that what he built became a tourist trap. His vision was about radically changing the way people live. He called the trees on his house tenants, and he made sure that the adjoining street couldn’t be driven on with cars….. His Hundertwasserhaus is the perfect example of how a house like that looks after several decades.

Kurt here. As I mentioned in the episode, I have not done load or carbon calculations for this building, but part of the point is not just that there are initial inputs to be offset (lifting trees) but also ongoing inputs (watering and maintaining trees, as well as keeping up the infrastructure to do these things over time). In short: keeping trees healthy and alive in the sky is more challenging than doing so on the ground, and if we think of this as an experiment, time will tell if the gains outweigh the monetary or carbon costs. It may well be that in some cases the net payoff over time is greater than the inputs required to sustain a project, but I personally have not seen that case being made in a mathematically rigorous way.

It’s unfortunate that the landscape architect you interviewed in this episode was so inaccurate in his discussion of architects performing structural analysis for vertical forests. Architects don’t do structural design, structural engineers do.

Kurt here – that conversation at the end was somewhat casual, unscripted and meant to be a short introduction, not an in-depth overview – nonetheless: I do apologize for not mentioning engineers. It is absolutely true that in these projects, at least the ones that are meant to become real and not just be renderings, a dedicated engineering team is going to be crucial to the execution. In the course of the conversation, I was trying to keep things simple and streamlined, focusing on the challenges, and did not mean to sell short the role of engineers in making these buildings possible, whether or not they are well-designed. But while architects may not do the actual calculations, they can and should be aware of the engineering challenges their (real or conceptual) designs will face in reality. I can’t speak for all architects, but when in architecture school, multiple Structures courses were a core part of the M Arch curriculum and we were taught to keep engineering in mind when designing buildings.

Just a note that the interviewee was definitely NOT a landscape architect, but a buildings architect

You guys should definitely look into Soviet city planning. There are great lessons to learn from Khrushchev-era cities, especially when it comes to public space, shaded and green areas. Look at Almaty, Khazakhstan, for instance. In the parts where they have preserved the original neighborhood structures, the inner courtyards (which are, by the way, huge in comparison with most European cities and are open to public), the trees that were planted are now creating urban jungles. Almaty is not an exception, anywhere you look, whenever they saved the original Soviet city planning, those cities (which used to be much-ridiculed in the West precisely in terms of urban planning) turned into green heavens with enormous public spaces which people actually use!

Roman, Shade was a good episode .

I take exception with the Vertical Forest in Milan comments. Directly adjacent to the Vertical Forest is the tree museum.

Over 100 trees of various species has been planted and is open to the general public.

Keep up the good work.

Best regards,

Tony

Some interesting discussion about plantings in this podcast but I didn’t hear too much about other ways of generating shade in cities—apologies if it was in there and I just got distracted and missed something. A hundred and fifty years ago—after the elevator but before air conditioning—many of the tall buildings in cities had operable windows and retractable awnings to shade the sides of the buildings exposed to sunshine. At street level, large retractable canvas awnings covered half the side walk—shading window shoppers and providing a space for retail advertising as a bonus. Advances in glazing have made it possible to filter out undesirable UV light and heat.

Many modern buildings incorporate a “brise-soleil”, a projecting awning made of metal louvers, screens, or tinted glass, to shade the windows and vertical surfaces of the building. Arcades at sidewalk level do make financial sense on retail buildings because they can attract window shoppers, keep them comfortable, and provide more advertising and lighting opportunities

In California, due to our ever-drying climate, the solution of adding more trees carries a risk of wildfire. So far, only suburban areas have been affected but if there were too many trees in downtown Oakland, would it bring the wild fire threat into the inner city? When trees are planted in California cities it’s important to consider the species for high drought tolerance and lowest risk of fuel contribution (dry leaves, brittle bark, high oil content) in case there is a fire.

Love your podcast it’s always informative and thought-provoking.

Loved the beginning of this podcast, but felt the second half was quite unfair to architects, Any architect who intends to put greenery will have put thought into the process. The weight of the tree + soil, the tree’s suitability to a higher altitude + higher winds, the process to get the tree there. As has been mentioned already in the comments, engineers are of course involved – trees are not simply added to a design as an afterthought as was implied by the discussion.

As for placing more trees at the base of the building, this is of course the most logical, but many buildings will be using the entire base footprint to gain the most sqm – to make the development viable. Also the plazas in front of these buildings are subject to the same urban planning laws that can make significant planting difficult – which you mentioned in this podcast.

Really enjoy this podcast so please be more careful with the misinformation next time!

As others above have noted, planting on top of buildings is often not done by architects at all (though they may be involved/have a say in the process), but by landscape architects and structural engineers. Additionally, many high rises with plantings on top of them fall somewhere between the two types you mention (greenroof and the vertical forest). It is very common and totally feasible to have planting with trees on a roof top deck or amenity space. And a greenroof often is just as difficult to figure out as any other planting, though with fewer benefits. These intermediate planting types can also be put on ground level OVER underground parking. Both of these methods are done ALL THE TIME, so it feels like a misrepresentation to say that there are a lot of cRAZy proposals for buildings completely covered in enormous amounts of tree cover. There MAY be some of these but there are so so many examples of practical and achievable on structure plantings.

An example of a public park on top of a building. The trees and spaces are for everyone.

https://www.capitalonecenter.com/the-perch

It would be great to hear the perspectives from a landscape architect who is actually the one designing these spaces. Architects are integral, but it’s misleading to always hear urban landscape commentary from someone is only a piece of the puzzle.

I would just like to mention that trees need water and LA had a big drought recently. It was mentioned that Los Angeles was a prairie and that implies the climate cannot naturally sustain large numbers of trees.

Great piece, Roman. Like a few others have noted, there are good examples of urban tree planting and green infrastructure in other cities. LA has only to look beyond itself to see how things can be done. I live in Atlanta (of course, a much wetter environment) where I volunteer with an organization called Trees Atlanta (treesatlanta.org). It was founded in 1985 by city leaders who saw that downtown Atlanta had become denuded of trees and worked to replant the parks and plazas. About 10 years later, the program moved into residential neighborhoods, where every weekend from October to March, volunteers turn out to plant 6-10 foot tall trees along streets and sometimes in homeowners front yards. TA surpassed 130,000 trees planted last year and we are going strong!

We are not winning, however. Rampant development is the same everywhere in the US, and tree canopy loss to new buildings and subdivisions is greater than our little army of volunteers can make up for. But the City of Atlanta is revising its tree ordinance to try to provide greater protection for existing trees, and it also supports tree planting by providing trees free of charge to homeowners. It’s hard work, and never-ending, but there is no alternative if we want to avoid broiling to death on the sidewalk.

Great episode! I was wondering if you are familiar with the ficus tree elimination controversy along 24th Street in San Francisco. Claims have been made that the trees are diseased, buckle the sidewalk, and encourage crime because of their dense shade. Some have already been cut down. It would be more than a shame to lose this shade, as well as the gorgeous green tunnel effect made by their canopy. For a glimpse of 24th Street before them, watch old episodes of Streets of San Francisco, or the Louis Malle film “Crackers” (featuring an embryonic Sean Penn and Christine Baranski), which show the stark sleaze of the 70s and early 80s perfectly. I hope they are replaced quickly if we do lose them, with perhaps the Chinese elms that line Folsom Street. I love ginkgo trees but they are very slow growing.

An example of wrong headed preservation can be seen along 18th Street between Bryant and Florida, where a six story apartment building is nearing completion. A great effort has been made to keep the messy, soot-prone strawberry madrone trees, which are perfectly nice in parks or yards, but make terrible street trees. All around the area the only new plantings are purple leafed plums, which are a rant subject for another time.

Anyway, thanks for your podcast!

I wish this episode had included discussions with licensed and practicing landscape architects (*spoiler, I am one). A landscape architect could have provided some perspective that was missing from the entire episode. I had a really hard time listing to an architect talk about the in-feasibility of over structure designs. I work primarily in urban settings and I deal with street tree planting and over-structure or rooftop installations on a daily basis and there was a lot of basic information missing in this story. Both at-grade planting and over-structure planting are tightly interconnected with other disciplines (structural, architectural, civil, plumbing, waterproofing, architectural, etc.) and we all have to jump through the hoops the municipalities have in place for us (fire access, vision triangles, utilities clearances). Lastly, the San Francisco Bay Area is lacking in space as well as housing and often the only viable option to get some green gathering space is to built roof terraces or over structure courtyards.

Please, please, please interview some urban planners or architects or landscape architects from Europe or Asia. These are themes we are dealing with on a daily basis! Daily! And yes, landscape architects should know how to calculate the wind impact on vegetation in high altitudes!