August 24th, 1814 marked the first and only time Washington D.C. was occupied by outside forces. The United States was two years into the War of 1812. They’d taken on Great Britain, which was then the greatest naval power in the world, and things weren’t looking great for the American troops defending D.C.

A wave of British forces overtook the city, and set fire to historic American landmarks including The Treasury building, the Capitol building, and even the White House. The siege became known as the “Burning of Washington.”

But then a freak occurrence — which in any other situation would’ve been a total disaster for D.C. — saved the city. Dark clouds began to form, which then turned into thunder in lightning, which then turned into a full-blown tornado. Which headed straight for the British setting fires around Capitol hill.

A number of British soldiers were killed by falling debris and the fires were extinguished by the storm. The British retreated to their ships. Thanks to a simple act of weather, the occupation of our nation’s capital was over within a little more than a day.

Of Weather and Warfare

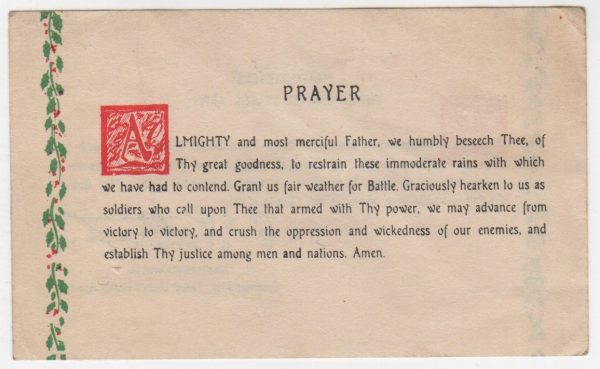

The “Storm That Saved Washington” was just one of countless times that weather played a crucial factor in war. Napoleon’s army wasn’t defeated by Russian forces so much as by a Russian winter. And during WWII, General Patton famously distributed 250,000 prayer cards to the army to enlist as many men as possible to pray for an end to the rain.

The battlefield has always been at the mercy of the climate, but there was a time in U.S. military history when we did more than just pray for advantageous weather. We tried to create it.

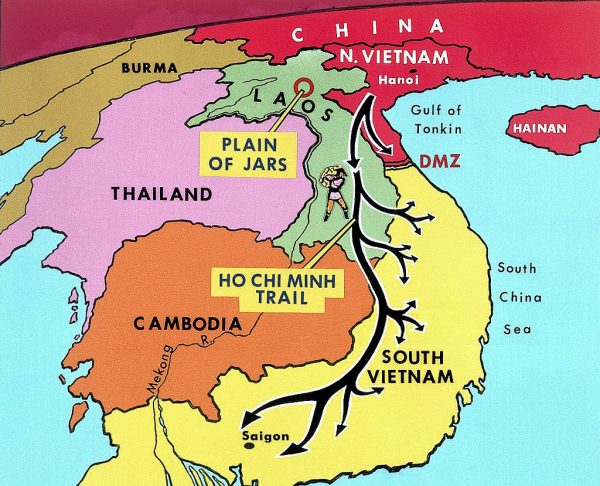

Beginning in the 1950s and continuing into the 1960s and 70s, the U.S. became deeply entangled in a war between North Vietnam (supported by the Soviet Union, China, and other communist allies) and South Vietnam (supported by the U.S. and other anti-communist allies).

The Vietnam War — or, as the Vietnamese called it, the American War — was unlike any the United States had ever engaged in. There was no front line — instead, the U.S. was involved in a guerrilla war with the Viet Cong, a communist force fighting primarily in the south.

One of the Viet Cong’s greatest advantages was the Ho Chi Minh Trail, a supply route that ran from North Vietnam through parts of Laos and Cambodia into South Vietnam. Hundreds of thousands of North Vietnamese troops used it to infiltrate the South, carrying weapons and supplies.

The trail network wound through an isolated region full of rugged mountains and dense jungles. The trail was made up of dirt paths and hand-made tunnels. Along the way were hidden bunkers, barracks, and even hospitals cleverly camouflaged from above.

The U.S. military tried disrupting the trail with bombing campaigns, and by plowing the jungle to strip the land. They also used deadly chemical defoliants, like Agent Orange. But none of those tactics seemed to work. Viet Cong soldiers just used secondary trails to bypass any disruptions.

In fact, there was only one thing that significantly slowed the flow of supplies and people on the Ho Chi Minh Trail: rain, which turned the trails to mud.

And so the Department of Defense decided that they should encourage this process by attempting to control the weather.

This was the beginning of a top secret military project called Operation Popeye. The goal was to actually create more rain in Southeast Asia by artificially extending and intensifying the naturally occurring monsoon season (which ran from April to October) by a month on either side.

Rain Dances to Cloud Seeding

Humans — especially military humans — have wanted to control the weather for a long time. Some rainmaking ceremonies have ancient roots. “It goes back to traditional rainmaking ceremonies,” explains historian Jim Fleming. “Turns out that if you do a rain dance for up to two weeks it’ll probably rain and then you can take credit for that.”

“If you do anything long enough and consistently enough it will rain and you can claim responsibility.”

Fleming says that in the 19th century — after the Civil War — a theory began to develop that major military operations were somehow disrupting the clouds and causing big rain storms. So in the 1890s, the federal government actually simulated battle activity in Texas during a drought. They fired off cannons and created explosions. “The locals loved it,” explains Fleming. “They loved to go out on the hillside and watch the cannonading, but it was during the monsoon season. So there was a really good chance it was going to rain anyway.”

This kind of experimentation continued from the 1890s into the early twentieth century. It only accelerated after the advent of the Cold War. The U.S. became increasingly paranoid that other countries, like the Soviet Union, were trying to develop their own nature-controlling technologies. Before the “space race” there was a kind of “weather race.”

There was a lot of money being poured into scientific research on weather control. And while many of these experiments didn’t yield very promising results, in 1946 one actually did.

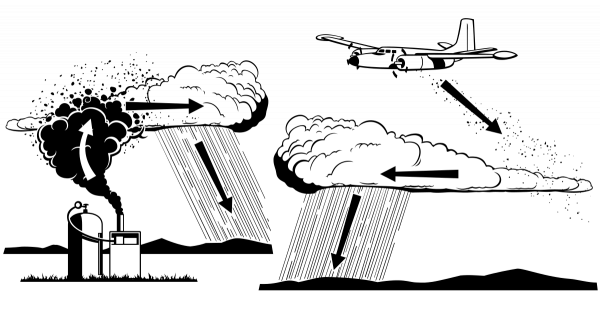

General Electric, best known today for appliances and other products, made a breakthrough. There, a scientist and Nobel laureate named Irving Langmuir was working in collaboration with a colleague named Vincent Schaefer, who developed a technique that employed dry ice to super-cool clouds in the sky. Clouds are essentially just tiny droplets of water suspended in the atmosphere. When the right conditions occur, water molecules in these clouds will condense together, and become heavy enough to fall to earth as rain or snow.

In parallel with that breakthrough, Bernard Vonnegut — brother of author Kurt Vonnegut — was also working as an atmospheric scientist at GE. In fact, you can see Bernard’s work shaping Kurt’s writing in novels like Cat’s Cradle, in which a mad scientist develops a dystopian weapon called “Ice-Nine” which can freeze things on contact. The book is a cautionary tale about the militarization of nature.

In parallel with that breakthrough, Bernard Vonnegut — brother of author Kurt Vonnegut — was also working as an atmospheric scientist at GE. In fact, you can see Bernard’s work shaping Kurt’s writing in novels like Cat’s Cradle, in which a mad scientist develops a dystopian weapon called “Ice-Nine” which can freeze things on contact. The book is a cautionary tale about the militarization of nature.

But Bernard’s research at GE actually helped lay the groundwork for that militarization. He discovered a new weather-related use for a compound called silver iodide. It had a hexagonal structure, like a snowflake. Bernard found that if you sprayed it into a cloud, it would trick the cloud into glaciating.

Between Bernard Vonnegut’s work and that of Langmuir and Schaefer, GE had developed the basis for cloud seeding.

GE was, understandably, very proud of their discovery, and issued a press release touting their ability to control the weather. But shortly after claiming responsibility for a storm that caused eight inches of snowfall in upstate New York, GE realized they might not want to be known for controlling the weather. Especially if the weather was destroying people’s property. Their lawyers advised them to ease off the publicity push.

Given the risk of negative public reaction and liability, weather modification research continued quietly. Scientists explored how it could be applied to hurricane intervention and drought relief — and, of course, warfare. Langmuir himself was excited about the military applications of his research, as were some political leaders.

With nuclear weapons now in play, the U.S. was looking forward and imagining how the country could get an edge in future wars. In a speech that Vice President Lyndon Johnson gave in 1962, he said:

“It lays … the foundation of a weather satellite that will permit man to determine the world’s cloud layer, and ultimately control the weather. And he who controls the weather will control the world.”

Cloud Seeding in Vietnam

By the time rainmaking had made its way to the Ho Chi Minh trail in Southeast Asia, it wasn’t a new technology, but it was still a closely-held secret. Operation Popeye was a Navy program with missions flown by Air Force pilots who were given limited information about what exactly they were doing.

“I never even imagined that’s what that group was doing,” recalls Brian Heckman, a former Air Force pilot, “until we got over there and showed up for the briefing and then they told us what the project was all about.” Heckman belonged to the 54th Weather Reconnaissance Squadron. They contributed to the 2,602 cloud seeding missions flown during Operation Popeye.

“We just went around looking for clouds to seed,” he says. Once they found a cloud to fly through, they’d flip a switch to ignite silver or lead iodide flares, then they’d wait and see if the cloud produced rainfall.

“There were times when we left an area that we had been working and it was obvious that there was a lot of rain storms going on.”

Operation Popeye had four main objectives: to turn the roads to mud, to cause landslides along roadways, to wash out river crossings, and to keep roads muddier for longer than usual. But cloud seeding at the utime, and even today, is far from an exact science. At best , the military could measure three things: what the average rainfall for that area was, what the estimated rainfall would have been, and what actually fell after a seeding mission. But, in the end, they couldn’t collect enough data to rigorously analyze the outcomes. “The rain is completely variable,” says Fleming. “You have a tremendous temporal variability, spatial variability, and that means that statistics are not robust about what your particular intervention did to that particular rainfall.”

And even if the U.S. military could make it rain, they couldn’t precisely control where the rain landed. One official described accidentally dumping a ton of rain on an American Special Forces camp.

Nevertheless, Operation Popeye was deemed effective enough to continue for five years, from 1967 to 1972.

But the program’s biggest problem wasn’t so much the lack of quantifiable success — it was the many ethical concerns it raised. Weather modification — especially in the context of war — raises a lot of thorny questions.

Unintended Effects & Ethical Challenges

The military justified their approach in Vietnam in part by arguing that increasing rainfall to create mud and wash out roads was preferable to more bombing. But the reality is the U.S. military still dropped a lot of bombs on Southeast Asia during the Vietnam war — over seven million tons of them. To this day, the government of Laos is still cleaning up all the undetonated bombs scattered across the country.

General Merrill McPeak says “we dropped more bombs on Laos than than we did on Germany and Japan altogether in World War II. So the tonnage of bombs dropped was enormous.” As a result, “the heavily used parts of the Ho Chi Minh Trail looked like the face of the moon … it was just a lunar landscape … nothing but dust.”

But just as it’s unclear how much rain was generated by Operation Popeye, it’s also unclear if the program actually prevented the military from dropping more bombs than they would have.

And, of course, there’s the question of messing with another country’s weather system, with its associated unpredictable consequences.

There are, for instance, documented cases in which weather modification may have caused harm. The silver iodide sprayed into clouds can be toxic to humans in concentrated doses, but it hasn’t been shown to have negative health effects when used for cloud seeding. Nevertheless, cloud seeding has been associated with other problems.

In 1947, Irving Langmuir’s research team at GE tried to break up a hurricane by dumping a lot of dry ice into it to see if it would collapse. But instead the hurricane changed trajectory, became stronger, and hit the Georgia coast. One death was reported as a result of the hurricane. And in 1952, the British Royal Air Force was conducting cloud seeding tests in Lynmouth, England, which may have accidentally triggered a devastating flood that killed 35 people.

Cloudy Skies & Seeds of Doubt

Ethical concerns ultimately helped end the U.S. military’s entire weather weaponization program. In 1971 Jack Anderson, a reporter for the Washington Post, published an article revealing that the U.S. was engaged in covert weather warfare in Vietnam. This report was corroborated by information leaked in the Pentagon Papers. The following year, in July of 1972, Seymour Hersh reported in the New York Times about Operation Popeye. Within days of the story’s publication, the entire program was officially ended and all cloud seeding missions stopped.

These reports caught the eye of a democratic senator from Rhode Island named Claiborne Pell who demanded details of the secret operation be declassified and released to the public. Because of his insight into the operation, Lt. Gen. Soyster was asked to testify in front of Senator Pell and the Committee on Foreign Relations. Soyster told them everything he knew.

These reports caught the eye of a democratic senator from Rhode Island named Claiborne Pell who demanded details of the secret operation be declassified and released to the public. Because of his insight into the operation, Lt. Gen. Soyster was asked to testify in front of Senator Pell and the Committee on Foreign Relations. Soyster told them everything he knew.

But the timing of these public revelations did not work out well for the Department of Defense. By 1972, the environmental movement in America was in full swing, and the Nixon administration was dealing with the early stages of the Watergate scandal. When it came out that the U.S. had been secretly engaging in hostile weather manipulation in Vietnam, it was dubbed “the Watergate of weather warfare.”

Research money for weather control rapidly disappeared, and in 1977 the U.S. signed an international agreement called the Environmental Modification Convention Treaty, or ENMOD for short, along with the Soviet Union and many other nations. They agreed to ban modification of the environment for hostile purposes. The treaty outlawed causing earthquakes and tsunamis, steering hurricanes, or tampering with the ionosphere. It also banned any other widespread, long-lasting, and severe damage to the environment. But there are questions about whether the ENMOD treaty was even that relevant.

“It was very easy to ban environmental warfare,” says Hamblin, “because you’re not giving up anything … because those things no longer were considered to be important parts of the arsenal.” At the time, it was presumed that any future war with, say, the Soviet Union, “was going to be a nuclear war … in which thermonuclear weapons [and] intercontinental ballistic missiles” would dominate.

Hamblin argues that giving up environmental warfare was more a gesture of global cooperation, rather than an actual step towards disarmament. After all, it’s hard to find something that can cause more widespread, long-lasting, or severe damage to the environment than nuclear weapons, which were not banned.” The ENMOD treaty can arguably be seen as progress but Hamblin “would encourage us all take a more cynical view of that and see that it was signed for very political purposes and really gave virtually nothing up.”

Climate Control and Geoengineering

The military interest in weather control had run its course, but cloud seeding is something that still takes place all over the world for another reason: money. A major percentage of the global economy is sensitive to the weather, from agriculture, to energy, insurance, and travel.

More than 50 countries openly have some form of weather modification program. China attempted to use cloud seeding to clear skies over the Beijing Olympics. There’s even a company in the UK that offers a wedding package that includes cloud seeding, which can be used to “burst” rain clouds and make them disappear. The company claims they can guarantee a rain-free wedding day for just $150,000.

As the conversation shifts away from the Cold War, to the present day threat of climate change, people are starting to talk about the use of “geoengineering” to address that larger problem.

A lot of suggestions have been thrown around, like brightening the clouds to reflect radiation back into space, or spraying reflective particles into the stratosphere to cool down the planet. People have proposed giant space umbrellas and even trying to change the orbit of the Earth so that it’s just a little bit further from the sun.

But changing the weather is one thing — changing the climate on a permanent scale is next level meddling. Many experts are highly doubtful that geoengineering can be used effectively to stop the warming of our planet. And anything we try would be extremely experimental, with unknown consequences.

“That’s the main issue” in Hamblin’s opinion. “Do we have a right to mess around … to tinker with things? Do we have the right to do that when we know it’s going to have global consequences?”

Weather systems are so complex that it’s pretty much hubris to think we can intervene in predictable ways. But as long as the stakes are high — whether it’s a war or the fate of the planet — people will probably keep trying to make it rain (or shine).

Comments (3)

Share

Seems to me that you have left the main question in my mind unanswered: what efforts, if any, have been made to end by weather modification the catastrophic droughts we have been experiencing, for example, in California.

The amount of ordnance dropped on Laos was indeed horrendous but the discussion would have been a bit more “balanced” if you had mentioned that explosives from World War I are still killing French farmers and this could add credence to your speculation that it may take a century or more for the Laotians to remove all our “bomblets”.

Great historical overview! and nicely laid out information!

Please also check out Weather Modification History (WMH), the world’s most comprehensive weather control archive with hundreds of verified historical facts, images, and videos.

https://weathermodificationhistory.com/