Lawyers have an ethics code. Journalists have an ethics code. Architects do, too. According to Ethical Standard 1.4 of the American Institute of Architects (AIA):

“Members should uphold human rights in all their professional endeavors.”

A group called Architects, Designers, and Planners for Social Responsibility (ADPSR) has taken the stance that there are some buildings that just should not have been built. Buildings that, by design, violate standards of human rights.

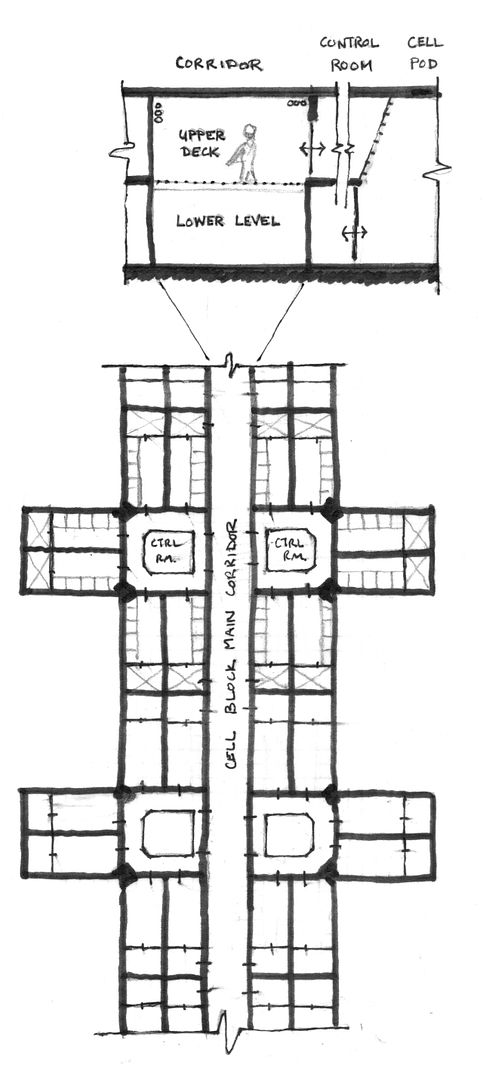

Specifically, this refers to prisons with execution chambers, or prisons that are designed keep people in long-term isolation (or as prison officials call it, “segregation”). The latter kind of prison is called a “supermax,” or “security housing unit” (SHU). There is no legal definition for solitary confinement, so it’s up for debate as to whether the SHU constitutes solitary confinement.

There has been a lot of controversy surrounding one SHU at a Northern California prison called Pelican Bay.

Pelican Bay State Prison was designed by San Francisco-based architecture firm KMD. KMD declined to speak with us for this story. But Jim Mueller, an architect with KMD who worked on Pelican Bay, told Architect Magazine: “The inmates have no contact with other inmates during the vast majority, if not all, of the day. They are only allowed out of their cells for very short periods of time for constitutionally required exercise periods.”

Life inside of the SHU at Pelican Bay means 22 to 23 hours a day inside of 7.5 by 12-foot room. It’s not a space that’s designed to keep you comfortable. But it’s not just these architectural features, that concern humanitarian activists and psychiatrists. It’s the amount of time many prisoners spend in that cells, alone, without any meaningful activity. Some psychiatrists, such as Terry Kupers, say there is a whole litany of effects that a SHU can have on a person: massive anxiety, paranoia, depression, concentration and memory problems, and loss of ability to control one’s anger (which can get a prisoner in trouble and lengthen the SHU sentence). In California, SHU inmates are 33 times more likely to commit suicide than other prisoners incarcerated elsewhere in the state. There are even reports of eye damage due to the restriction on distance viewing. Terry Kupers says that a SHU ”destroys people as human beings.”

Terry Kupers at the Conference on Solitary Confinement and Human Rights, November 2012:

Compared with some other prisons in the California system, the Pelican Bay SHU has some redeeming architectural features. Inmates can get natural light from skylights outside of their cells, which drifts in through doors made of perforated metal. These porous doors also allow for inmates to communicate with each other, even though there are no lines of sight to any prisoner from within the cell.

But on the other hand, cells don’t have windows. Inmates never get to see the horizon. The only times prisoners get to leave the cell is to visit the shower, or the exercise yard—which is an empty, windowless room not that much bigger than a cell, with twenty-foot high concrete walls.

(KQED and the Center for Investigative Reporting launched an investigation on Pelican Bay in February 2013)

Again, there is no universally accepted definition of solitary confinement. But some groups, like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, have gone beyond calling the SHU solitary confinement—they call it torture. In 2011, the UN Special Rapporteur on torture said anything over 15 days in solitary confinement is a human rights abuse—which other sources have interpreted as torture.

So if it is the ethical code of architects to promote human rights…what is their responsibility to the people who are incarcerated in their buildings?

Enter Raphael Sperry, a San Francisco-based architect and president of ADPSR. He believes it’s up to architects to lead the charge against these buildings. Sperry and the ADPSR are trying to get the American Institute of Architects to adopt an amendment to their ethics code:

“Members shall not design spaces intended for execution or for torture or other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment, including prolonged solitary confinement.”

This episode is a special collaboration between 99% Invisible and the podcast Life of the Law. 99% Invisible producer Sam Greenspan spoke with Raphael Sperry and Terry Kupers about the effects of these kinds of prisons on the people who inhabit them, and what they say about the practice of architecture as a whole in the US.

In addition, Life of the Law’s Nancy Mullane drove very, very far to visit the SHU at Pelican Bay State Prison, where she spoke with prisoners and prison officials about life in the SHU.

Comments (9)

Share

This was an interesting podcast but lacked an important perspective, in my opinion, in that we don’t hear any serious attempt to explain the reasons for the practice of isolating prisoners. I am not especially well informed on this point, but my understanding is that many of the people in isolation are gang members. The significance of that is that if gang leaders can communicate with other prisoners, then they can get messages to gang members in the outside world. If they can do that, then they can reach out beyond the prison walls to strike at the families of guards, prosecutors, etc. In this way, the prisoners gain power over the prisons and the justice system. .

I read an article some years ago about the Aryan Brotherhood. To say that they are an extremely violent group understates the matter considerably; their method for achieving power is terror, pure and simple. The chilling quote in the article — from a guard — was that the guards control the prison’s perimeter, the Brotherhood runs the prison.

So, there may be a different solution than the ones employed today, but I felt this otherwise interesting story misrepresented the situation somewhat in not acknowledging the serious problem high-security prisons are designed to address.

The problem with architects not designing this facilities, is that there are going to be built anyhow, but instead of an architect, it will be an engineer who cares even less for the inmates. Architects should look at ways to make the SHU better for prisoners. The should also be other civil liberties groups trying to ban SHUs, but that is going to take time.

“It’s not our place to decide if he deserves this. We’re just here to do a job.”

So I just listened to this episode and later in the week, I found myself looking into this indie game called “Prison Architect”. I’m not sure if it’s even relevant, but I thought I’d leave this here:

http://www.wired.co.uk/news/archive/2011-11/30/prison-architect

One the key places that Architects can assist everyone working to raise the quality of life for kids, is to ask and question who is being housed and processed in their buildings and projects. Many juveniles are being housed in detention facilities with adult males. Many juveniles, undocumented kids, are being housed in substandard facilities (they do not have enough money to pay for pro bono attorneys). Other are interviewed & processed in holding cells and centers that are child-unfriendly; especially for a kid who has been abused & exploited. http://www.real-stories-gallery.org

Why the fuck does every random twat feel entitled to an opinion on everything?

They’re fucking architects. Their wishes and feelings regarding prisoners are the most absurdly, earth-shatteringly, profoundly IRRELEVANT thing I can imagine. I literally can’t imagine a smaller unit of importance than architects’ thoughts on inmate conditions.

You know whose opinion does matter? The victims of crime. And those people aren’t getting justice if the criminal isn’t getting damn-near-tortured.

What about the people who are wrongly convicted? A number of people have spent years on death row for crimes they didn’t commit.

CL, justice is served when the perpetrator looses his or her freedom for a matter of years or a lifetime. At the same time the public is protected from further acts of violence. What good does it do to torture someone if it only leads to his or her becoming sicker and more violent and the torturers becoming less human? Do we really want people who have served their time to come out worse people than they were when they went in? We should do our best to rehabilitate prisoners so they can become contributing members of society.

The article is from the point of view of architects and is about their commitment to doing no harm. I think it is a fine, thoughtful article.

Can’t agree more with you CL, as you just exhibited the role of a random twat.

Firstly, for not subscribing to the notion of basic human rights, and secondly for not understanding the supposed intended role of the prison system, which is rehabilitation.

And then of course lastly, architects’ chief concern and responsibility is toward the occupants of buildings, regardless of who they are.

The system we have today for incarceration has not really changed over time. They try to say there making things better but really there only making things better for the very low security prisons where there never really was a problem.