Imagine for a moment the year 1800. A doctor is meeting with a patient – most likely in the patient’s home. The patient is complaining about shortness of breath. A cough, a fever. The doctor might check the patient’s pulse or feel their belly, but unlike today, what’s happening inside of the patient’s body is basically unknowable. There’s no MRI. No X-rays. The living body is like a black box that can’t be opened.

The only way for a doctor to figure out what was wrong with a patient was to ask them, and as a result patients’ accounts of their symptoms were seen as diseases in themselves. While today a fever is seen as a symptom of some underlying disease like the flu, back then the fever was essentially regarded as the disease itself.

But in the early 1800s, an invention came along that changed everything. Suddenly the doctor could clearly hear what was happening inside the body. The heart, the lungs, the breath. This revolutionary device was the stethoscope.

The inventor of the stethoscope was a French doctor named René Laennec. In medical school, he had learned to practice percussion – a technique in which doctors tap their fingers against a patient’s chest and listen to the sound to try and hear what’s going on inside.

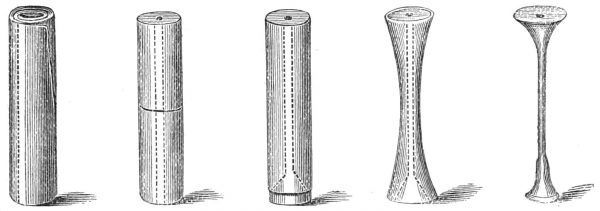

One day, he tried percussing a patient but had trouble hearing. So he rolled up his notebook into a little cylinder and put one end on the patient’s chest and one end in his ear. He was so impressed by the quality of the sound that he decided to construct a device for listening to the internal sounds of the body.

The result was the original stethoscope. Laennec had invented a way to hear the inner workings of the human body. Now he needed to connect the sounds he was hearing with what was happening anatomically inside the patient’s body.

To do this, Laennec listened to people right before they died, and then connected these sounds to discoveries made during the autopsy. Soon, Laennec made some key discoveries using his stethoscope. For example, he found that when a person has fluid beneath their lungs, they make a bleating sound, kind of like a goat. A sound he called egophony. He also discovered sounds that tracked with the different stages of tuberculosis.

Laennec published his results, and soon doctors were making other important discoveries that changed the way people thought about disease. Little by little our entire understanding of disease shifted from one centered around symptoms to one centered around objective observation of the body. Medical language completely changed, as doctors invented new anatomical words for diseases, like Bronchitis, which means the inflammation of the bronchial tubes.

In parallel, the device evolved as well. In the 1840s, doctors began experimenting with flexible tubing and soon an Irish physician invented the binaural stethoscope design with two earpieces that we still use.

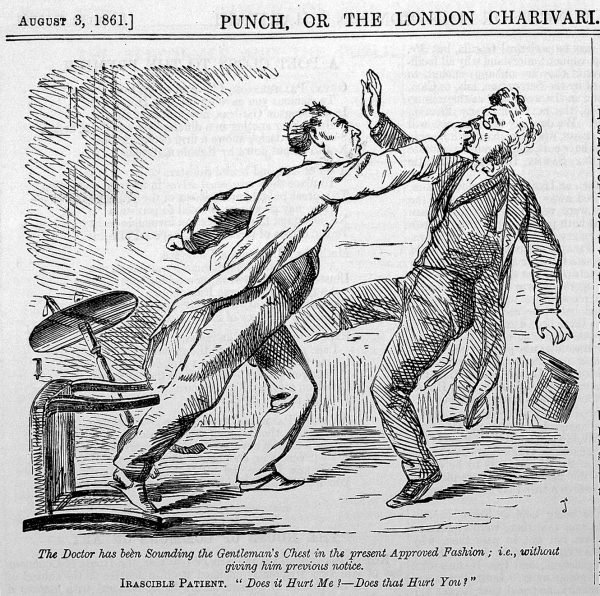

This evolving device got doctors thinking about disease in new ways, changing their dynamic with patients and giving doctors a lot more power. Before the stethoscope, to be sick, the patient had to feel sick. After the stethoscope, it didn’t matter what patients thought was wrong with them, it mattered more what the doctor found.

René Laennec actually felt that patient’s accounts of their own disease were still important, but the quest for objective information about disease was underway, and the stethoscope was just the beginning. Now we have X-rays, CT scanners and MRI and PET scans. All of these devices are basically trading upon the same paradigm that the stethoscope created: that doctors should be able to detect abnormalities inside the body to reach a diagnosis, regardless of how the patient is feeling.

These new technologies have led to so many important discoveries about the human body and disease. Today, we can spot tumors before they become life threatening and diagnose problems like high blood pressure before they causes heart disease. But this new way of thinking has also pushed doctors and patients farther apart. The doctor is no longer in your bedroom interviewing you about every detail of your experience.

René Laennec died in 1826 at the age of 45, mostly likely of tuberculosis, a disease he and his stethoscope helped us understand. It’s been 200 years since he first rolled up his note book and pressed it to that patient’s chest. Medicine looks completely different than it did back then, but somehow the stethoscope has endured.

It’s no longer a wooden cylinder, but to this day, when you walk into a doctor’s office for a routine exam, you can expect to feel the familiar stethoscope on your back.

But that could be changing. Powerful imaging technologies like ultrasound have made the stethoscope exam less critical to the diagnostic process. Medical students aren’t as good as using stethoscopes as they used to be, and across the board doctors today rely less on the stethoscope to make diagnoses. The rise of portable ultrasound has some doctors arguing that we don’t need the stethoscope anymore. They say that if you have that technology right at the bedside, why not use it right away? Ultrasound is an incredible tool, but it still isn’t widely available in many developing countries, and even in the United States it’s expensive. Right now the stethoscope functions as a screening tool so that patients don’t need to go get an expensive ultrasound unless they need one.

Dr. Andrew Bomback is a nephrologist and an assistant professor at Columbia. He still uses his stethoscope, but he says that in general doctors aren’t as good at listening to the body as they once were, and they rely on the stethoscope exam less and less to make a diagnosis. “It’s become almost a ritual more than an actual tool in terms of making diagnosis,” Bomback explains.

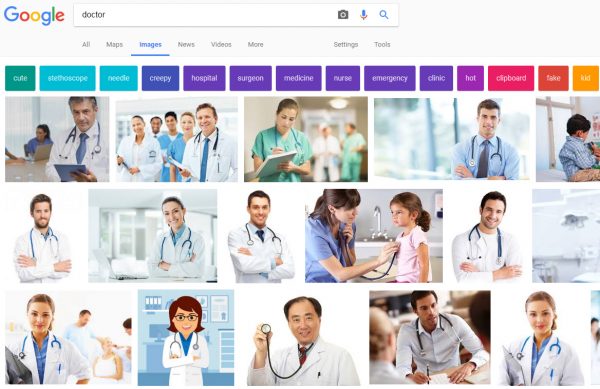

Regardless of how it’s used, the stethoscope remains omnipresent in our culture. Do a Google image search for doctor, and you will see what a physician is supposed to look like. The plurality of the doctors pictured on the first page of results are white men in white coats. Some of them are peering inside patient’s ears, others are writing something down on a clipboard. But all of them have stethoscopes.

And they are wearing the stethoscope in the exact same way–which is like a shawl around the back of the neck. Andrew Bomback says this way of wearing the stethoscope is a relatively recent fashion trend, probably borrowed from TV shows like ER and Scrubs. Doctors used to wear their stethoscopes dangling down the front of the shirt like a tie, which was practical. If you needed to use it quickly you could just pop it into your ears. Bomback observes that “it’s almost like this new version of wearing it like a scarf or a shawl is almost a concession that it’s more a fashion accessory than actually a tool that we’re using.”

But even if it’s become a fashion accessory, Dr. Bomback isn’t ready to give up his stethoscope. He says it’s an important conduit to connecting with his patients. Physical contact between a doctor and a patient has become increasingly rare. Doctors visits are short and physicians often spend much of time staring at a computer screen. Bomback says the stethoscope provides an important opportunity for intimacy.

“The stethoscope is still a part of the exam” he says, “aligned with the laying on of hands” associated with healers. “When we go to do the physical exam, we move away from our desk, we move away from the computer, and we stand right next to the patient and it’s a much more intimate conversation.”

Bomback says he thinks the stethoscope lives on in part to keep doctors and patients from drifting too far apart. To make sure doctors keep close to their patients, and keep listening.

Comments (11)

Share

“Most of the doctors pictured on the first page of results are white men in white coats.”

That does not even reflect your own screenshot. Why lie?

Every image has someone wearing a stethoscope (the main point), and most are white, most are men and most are wearing white coats. There was certainly no attempt to “lie,” but “most” has been changed to “plurality” to eliminate any ambiguity.

This episode had my eyes rolling out of my head. I am a nurse on a cardiology unit, and I’d like to share a few things that might help round out this episode. First of all, I don’t wear my stethoscope like a damn necktie, because the bell end is a little heavy and would swing around like a mace at pubic bone level. Secondly, I don’t wear it like a shawl to make my patients feel like their medical experience is complete, or because I saw it on ER. I wear it or keep it in my pocket, because it’s comfortable and essential to my job. Some doctors may be losing touch with patients and need some sort of a prop to help bring them closer. Well thank god it’s just a given that your nurse will actually assess you, listen to you, and physically touch you.

We listen to bowel sounds to ensure your gut is working after surgery. We can listen for a fast irregular heartbeat and tell you if that $500 EKG is necessary. We can correlate lung sounds and vital signs and determine in 30 seconds if a patient needs diuretics. We document real-time flowsheets of auditory evidence that guides nursing judgment and decisions. Nurses are constantly using stethoscopes to direct care, so it’s supremely irritating to hear an MD wax on about stethoscopes being some quaint accessory. Doctors ARE using stethoscopes. It’s just via a nurse telling them the patient is drowning in their own fluids, needs more expensive imaging, etc.

“Opportunity for intimacy”?!?! Maybe stethoscopes will become obsolete for physicians because they aren’t using them to good effect. But I assure you, other people are.

*screaming*

This was an outstanding podcast that encapsulates a hot debate in medicine and among medical educators. I am the director of medical education at a US medical school. Our faculty are split between those who believe that meticulous instruction in using a stethoscope (and the physical exam more broadly) is essential to training young physicians. Other faculty — not necessarily younger ones — argue that except for a few gross screening maneuvers, the stethoscope is becoming obsolete and is little better than reading entrails in diagnostic precision.

We all agree, however, that physical contact between patient and physician is essential, and the physical examination provides that opportunity. As importantly, the stethoscope is a symbol of the physician and an important link to its roots. Kudos on illustrating each of these points far better than I’ve stated here.

Anna is obviously right, but she’s younger than me. As someone who was a medical student and intern in the 1970’s..early 80’s I’m one of few people who can tell you about this. Ok, look at Ben Casey the TV show versus ER, the profession of doctor and nurse became way, way grubbier (for nurse, one way). The number of orderlies (CNA’s, now) plummetted and Anna and I became orderlies during the same period. If you were in medical training about 1980, how you wore the stethoscope was a THING that was commented upon. If you were going to be seen as a more active hands on doctor (and that was considered cool), then you wore it as a shawl. This was a class statement. This was an age statement. Older, richer, established doctors wore the stethoscope down. During this same period, the shoes we wear changed. We wore scrubs. AND we changed the way we wore the stethoscope because we ran around. Patient transport, collection of lab data, phlebotomy outside of regular hours and a host of new actually skilled procedures…all the intern/medical student and sometimes nurse.

(oh yeah, and the respect of the profession plummeted but I think you can already see that with Anna’s comment. During the same period the AMA came out against the need for higher nursing staffing, training and pay and I quit the AMA in protest).

Thank you for your perspective. I clearly wasn’t around for the shift in stethoscope style in the 80s, but it makes so much more sense with the context you’ve given. I work with many physicians who I deeply respect, and who work extremely hard for our patients, so I hope my comment wasn’t interpreted as a dig toward MDs in general. It was just bizarre and insulting to hear a podcast about a tool I use daily without the word “nurse” mentioned once. I suppose the MD title doesn’t garner the same respect that it used to, but at least they aren’t erased from the conversation completely. I have been a nurse for a few years now, but I am still finding all the 100-year-old doctor vs. nurse baggage and weird power dynamics really tiresome.

Mainly, I think the point should have been made that the roles of doctors and nurses have evolved to accommodate a super complex and expensive acute care population. To that end, nurses really are the “eyes and ears” of physicians who are given far too many patients to assess or keep track of thoroughly. I just think it works better for everyone (especially the patient) to leave the ego at the door and acknowledge each other’s value to the team.

Everything that Anna said, plus…..the fancy word for shortness of breath is dys-pnea not dyp-snea. I’m also a nurse.

I’m a pediatric hospitalist and the stethoscope is indispensable for my practice. It is not a symbol. It is not a fashion statement. It is my single most important diagnostic device.

The most common causes of pediatric hospital admission (asthma, bronchiolitis, and pneumonia) can all be distinguished by a skilled examiner using a stethoscope in about 10 seconds. Radiographs are costly, take time, and expose children to ionizing radiation. Ultrasound is not widely available at the bedside and even for skilled practitioners takes much longer than auscultation (listening with a stethoscope), not to mention it requires slathering gel on your patient.

I certainly don’t speak for all providers and there are many physicians (ophthalmologists, urologists, psychiatrists, physical medicine and rehabilitation, etc.) for whom a stethoscope is generally unnecessary.

I wear mine shawl-style. I find it uncomfortably tight when worn around my neck. This also keeps the bell from hitting my patients.

Would you consider doing an episode on the white coat?

I enjoyed the podcast for the history lesson, but I agree with Anna about modern assessment. I’m a paramedic. We have an ambulance’s worth of equipment, not an office or hospital full of it. We might begin treating a patient in a ditch. A stethoscope is an essential tool, especially with pulmonary (lung) illness or chest injury. In fact, the longer I practice medicine, the more I respect old fashioned tools for understanding a patient. Labs and ultrasounds and other tools are good medicine. But they augment an “intimate” clinical assessment; they don’t replace it. I highly respect doctors and nurses who do a good clinical assessment before extra tests are ordered.

So, I shared this with one of my bosses, a prominent gastroenterologist, and he cried foul! Repeatedly. Counterpoints to the episode: 1) He says he and other New York providers were rocking the slung stethoscope DECADES prior to Grey’s Anatomy; and 2) The switch from tie to shawl had nothing to do with technology, the impending obsolescence of the stethoscope, or style. It had to do with changes in the length of stethoscopes. According to the boss, stethoscopes used to be much shorter. As such, they could easily be clipped around the neck with the business end resting at a functional level just above the waistline. Over time; however, stethoscopes became longer and longer to keep providers’ faces further and further away from a potentially coughing and wheezing tuberculosis cases. Longer stethoscopes could no longer be worn clipped around the neck because longer stethoscopes place the business end well below the waistline. Pause a moment to think that through. Conclusions: MDs got more and more cautious. Stethoscopes got longer and longer. Stethoscopes moved from neck to shoulders for purely practical reasons. He wore it first. He wore it better.

Beautiful analysis. Thanks. Beautifully done.