The middle of the 20th Century was a golden age for road travel in the United States. Cars had become cheap and spacious enough to carry families comfortably for hundreds of miles. The Interstate Highway System had started to connect the country’s smaller roads in a vast nationwide network. Finally, tourists could make their way from New York to California, seeing the grandeur of America along the way. That freedom and mobility, however, was not equally available to everyone.

In 1956, the year that federal funding made the Interstate Highway System possible, Jim Crow was still the law of the land. In the South, racial segregation was enforced by law — and had been since shortly after Reconstruction. In many parts of the North, the codes were enforced in practice. This reality made cross-country trips complicated, and sometimes even perilous, for black travelers.

Some African-American tourists would drive all night instead of trying to find lodging in an unfamiliar and possibly dangerous town. They would pack picnics so they could avoid stopping at restaurants that might refuse to serve them. Some people would even carry portable toilets in the trunks of their cars, knowing there was a good chance they would be turned away from roadside restrooms.

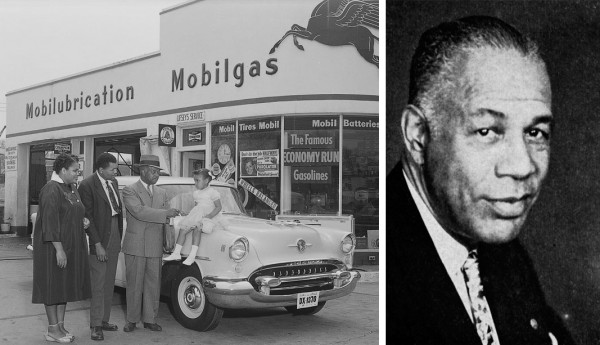

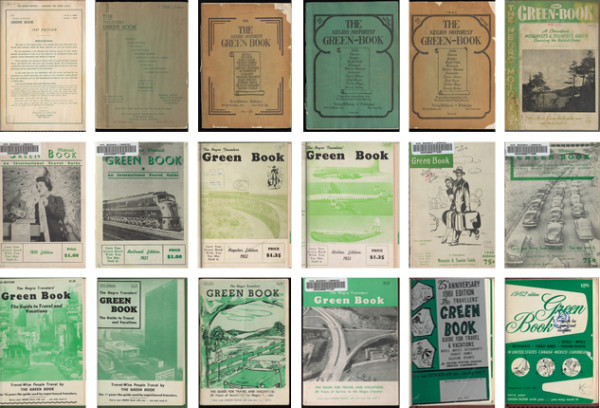

But in 1936, a man named Victor Hugo Green started a travel guide to make life on the road easier and safer for black motorists.

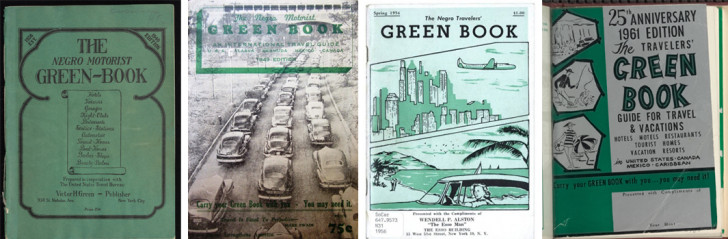

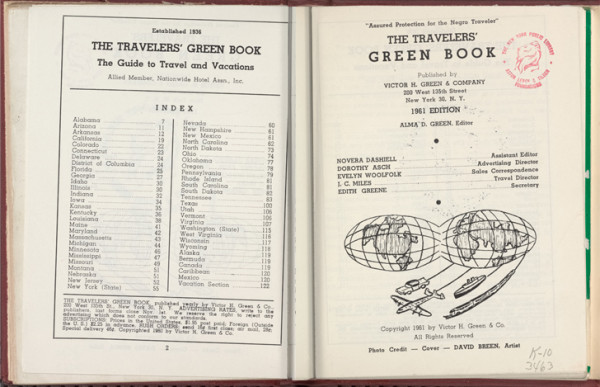

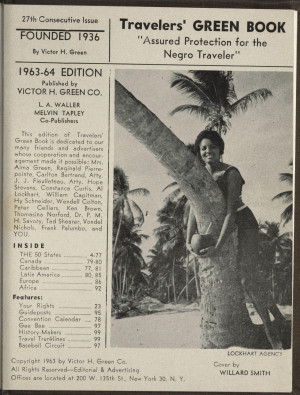

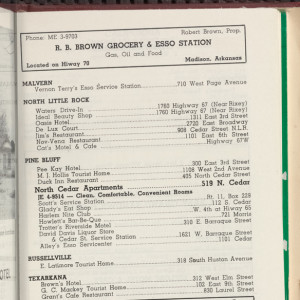

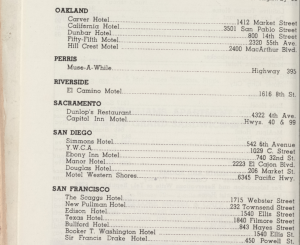

The guide listed, state by state, the restaurants, hotels, service stations, and other businesses that would welcome African-American travelers. Green called it “The Negro Motorist Green Book,” or “The Green Book,” for short.

Green did not have the most obvious background for starting a travel guide. He was not in the tourism industry, nor was he a writer; he was a mailman in Hackensack, New Jersey, who kept hearing stories about discrimination on the road. He was also not the first to come up with an idea of this kind. Jewish tourists, who also faced discrimination while traveling, had relied on similar guides to steer them away from hotels with a “Gentiles Only” policy.

In the Green Book’s early days, it wasn’t easy to compile listings from across the country, says playwright, author, and filmmaker Calvin Alexander Ramsey, who has researched the history of the guide. So Ramsey says Green tapped into a nationwide network of African-American letter carriers. These postal workers, familiar with their local communities, were ideally suited to help fill in the gaps from state to state.

As the Green Book caught on, businesses began to get in touch, asking to be listed. Black newspapers signed on as sponsors. The United States Travel Bureau helped spread the word about the guide. Eventually, Green retired from mail delivery to work full-time on the guide and to open a travel agency.

Distribution of the guide remained a challenge, says Ramsey, and Green relied on informal networks like the National Urban League, the NAACP, masonic lodges, and churches around the country.

There was also a big corporate sponsor that helped the guide expand its reach: Esso, also known as Standard Oil, and now known as ExxonMobil. The company may have supported the guide out of a sense of fairness and equality. John D. Rockefeller, who founded Standard Oil in 1870, had married into a family of abolitionists and voted for Abraham Lincoln. But there were certainly economic motivators as well. If African-American tourists felt comfortable on the road, they would travel more and buy more gas.

The Green Book would come to feature listings across all 50 states as well as locations in Canada, Mexico, and the Caribbean. About 15,000 copies were printed each year.

As the NAACP pushed for the 1964 Civil Rights Act, which outlawed racial discrimination, the black traveler became a key example in their argument to Congress. They appealed to that vision of the iconic family road trip, and the freedom to explore America by car. In his testimony before Senate in 1963, the NAACP’s Executive Secretary Roy Wilkins asked senators to imagine themselves as black travelers:

How far do you drive each day? Where and under what conditions can you and your family eat? Where can they use a restroom? Can you stop driving after a reasonable day behind the wheel, or must you drive until you reach a city where relatives or friends will accommodate you and yours for the night? Will your children be denied a soft drink or an ice cream cone because they are not white?

Framing the narrative of civil rights as a family travel narrative helped convince senators to vote for the bill. The last edition of the book was published in 1966.

At the time of their publication, Green Books were relatively inexpensive and imminently practical, something bought to be used. Today, copies of the Green Book are scarce and valuable, collector’s items that, thankfully, are no longer needed to make travelers safe on the road. One recently sold at auction for over $20,000.

Comments (7)

Share

I remember yall made another episode about this same topic but weirdly it’s not in the “more in subjects” session. I was gonna listen to both consecutively to see what’s new but I can’t.

It’s a rebroadcast. Look at the episode numbers for this and the previous episodes.

They removed the old link and now you can only find this episode. Check YT because someone uploaded it.

Great episode!

While obviously things have come a long way since the 1960’s for Black travelers, I think it wouldn’t be too far fetched to still produce such a thing. It would have to be more nuanced, but we do know, there are still men and women, politicians and police, business owners and citizens that make endless trouble for people of color in both their daily and cross country travels. Profiling, a recent up-surge in white supremacy under the current presidency, and near constant reminders both on the news and off, that many people of color are treated as second and third class citizens, whose very lives hold no value for many, make this a heartening reminder, not entirely of how things were, but how they could be again, if we are not very deliberate and determined to insure civility and care for all our citizens. This is a wonderful piece and I feel grateful some time was dedicated to it, and I look forward to hearing more about Mr. Green and his compatriots in creating this beautiful resource from his insight, vision and determination.

My parents should have had this guidebook before attempting to drive through Kensington, CA in the late 60’s. Kensington is still not a freindly place for D.W.B.

Visit Green Book sites on our map—find one near you! https://historypin.org/en/greenbook