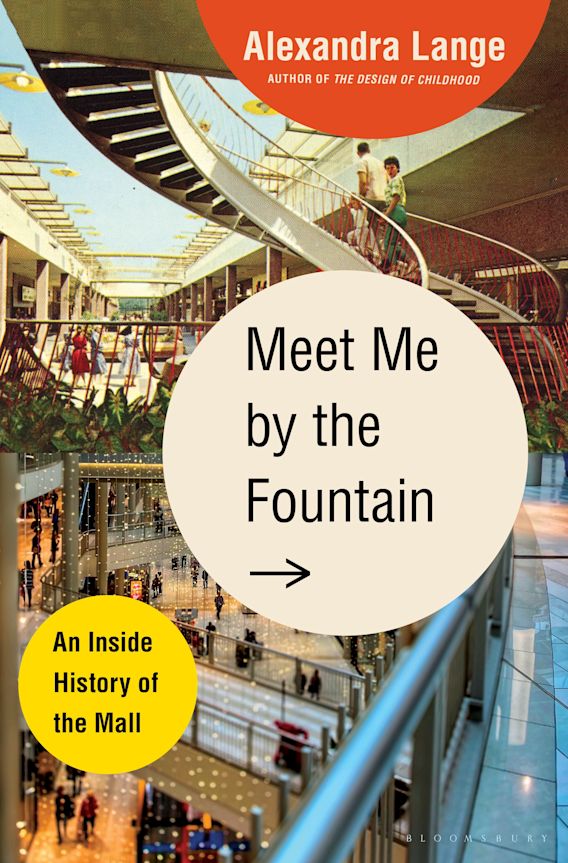

Like it or not, no teenager in America in the 1980s could avoid the gravitational pull of the mall, not even author Alexandra Lange. In her new book, Meet Me by the Fountain, Lange writes about how malls were conceptually born out of a lack of space for people to convene in American suburbs. Despite the fact indoor shopping malls are no longer in their heyday, malls have not gone away completely. Lange writes about the history of mall culture, and how the mall became a ubiquitous part of American life.

The earliest malls were simply two lines of shops facing each other, with a department store at each end, and a covered central area that usually featured fountains, plants, and benches. It was the brainchild of Victor Gruen, an emigré from Austria, who, when moving to the U.S., brought with him vivid memories of the charm of public life in Vienna, where there was a strong culture of gathering around fountains in the street. When Gruen moved to America, he started designing freestanding department stores in cities, but felt crushed by the landscape of the stores because they lacked the vivaciousness he had loved about European cities. There was nowhere to meet your friends, for example, or to just sit at a café.

Then, in the early 1940s, after a spontaneous visit to Detroit’s suburbs, Gruen had an idea: he would pitch department store owners on creating indoor shopping centers. The plan sounded intriguing to investors, and over the next several years, four such malls got propelled into development, called Northland, Southland, Eastland, and Westland.

Gruen’s vision for the early mall was more of a mixed-use hub of community activity. Gruen’s malls consisted of shops and department stores, but also post offices and doctor’s offices. Those early malls, which Gruen wrote about in great detail in the 1940s and 50s, also had church spaces and nurseries. The idea was that the mall would have enough community functions that it could sufficiently replace the downtown. Over time, going to the mall became known ubiquitously as an American pastime.

The mall was supposed to have enough community space that it could sufficiently replace the downtown. Over time, going to the mall became known ubiquitously as an American pastime.

So are malls responsible for killing the downtown? Where did the rise of big entertainment malls come from? What will happen to the mall in a post-pandemic world? And what happens when malls begin to serve as de facto public spaces? To help us answer these questions, we spoke with Alexandra Lange, design critic and longtime friend of the show. Her book, Meet Me by the Fountain, is great, and is out today!

Comments (1)

Share

Endlessly fascinating topic.

As an Australian, I feel strangely compelled (by pride or shame?) to point out that Westfield didn’t get bought out by Australians. It was started in Australia in the 1950s by a young European emigré, Frank Lowy – in a field in the western suburbs of Sydney. It’s always struck me as incredibly ironic – not only because Westfield is a comparatively high end brand, named after one of the most socio-economically disadvantaged areas of Sydney; but also because of the huge global expansion of Westfield, which has seen it export the quintessentially US-style mall back into the USA.