After World War I, in Frankfurt, Germany, the city government was taking on a big project. A lot of residents were in dire straits, and in the second half of the 1920s, the city built over 10,000 public housing units. It was some of the earliest modern architecture — simple, clean, and uniform. The massive housing effort was, in many ways, eye-poppingly impressive, with all new construction and sleek, cutting edge architecture. But one room in these new housing units was far and away the most lauded and influential: and that was the kitchen.

Many consider the Frankfurt Kitchen to be nothing less than the first modern kitchen. A few of these kitchens still exist, some in museums. And it’s strange to see one there, because to modern eyes, it doesn’t appear to be high art. It just looks like a kitchen.

But so many things that we totally take for granted now as standard kitchen features were pretty unheard of before they showed up in the Frankfurt Kitchen. Things like a cookstove that wasn’t also your house’s heat source; well-planned storage to stash your plates and glasses; a way to wash dishes that didn’t involve hauling a heavy tub of water into the house; and slatted racks for drying dishes over the countertops.

Standardization ruled this design. Before, for example, there weren’t long surfaces that were uniform in height. Most kitchens just had whatever random assortment of tables you could throw in them. The Frankfurt Kitchen, countertops and all, was mass-produced off-site — which was a totally new phenomenon. It was designed to fit in relatively small apartments. So, here is perhaps the most visibly striking thing about the kitchen: it is super compact.

Standardization ruled this design. Before, for example, there weren’t long surfaces that were uniform in height. Most kitchens just had whatever random assortment of tables you could throw in them. The Frankfurt Kitchen, countertops and all, was mass-produced off-site — which was a totally new phenomenon. It was designed to fit in relatively small apartments. So, here is perhaps the most visibly striking thing about the kitchen: it is super compact.

To the woman who designed it, Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, the Frankfurt Kitchen was a revolution. Not just because it was part of a huge effort to get people housed, but because of its wildly efficient layout. It was designed to fit, and to bring modern appliances and architecture to the masses — but it was also designed to conserve the user’s energy. To make cooking as fast and easy as possible. And to Schütte-Lihotzky, that ease was political.

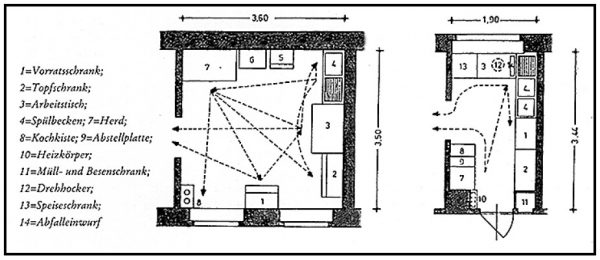

Schutte-Lihotzky was methodical and scientific in her planning. She studied how women used their kitchens, and mapped out their movements like football plays or complex dance steps, with little lines across the floor, and streamlined accordingly, until she came up with this very design – a kitchen in which no single step or reach of the arm was unnecessary.

From the 1920s into the present, many architects and home cooks celebrated, even revered the Frankfurt Kitchen. And the echoes of her design are still everywhere. But Schütte-Lihotzky’s feminist legacy is a bit more complicated. She was revolutionary in that she paid attention to the kitchen, a space that had historically been neglected by architects and designers. She laid everything out with the goal of lessening the burden of housework for women. But by the time Schütte-Lihotzky designed this revolutionary kitchen, many feminists had already been questioning whether private kitchens could ever be designed to liberate women. Or whether they were irredeemable, and needed to be abolished. And their stories show just how much design can accomplish… and how much it can’t.

Kitchen History

For much of modern history, in most cultures, kitchens were the realm of women, and of servants who worked in the home. And for the most part, they were dismal places. One American feminist from the 19th century wrote of “roasted ladies,” scorched and sooty from preparing the meals day in and day out. On top of raising children, plus hand-washing and drying laundry, and sometimes juggling factory jobs outside the home, preparing the 1095 meals a year for the family was regarded as absolute drudgery by many women.

Absolute drudgery that was also unpaid. And in the years after the Civil War, a number of American feminists started to argue that uncompensated housework was keeping women financially and intellectually oppressed. And one of the ways they thought they could change that was through urban design.

In the US, one of the early activists who called for a design solution to end women’s unpaid labor was a writer and organizer named Melusina Fay Peirce.

Peirce started the “Cambridge Cooperative Housekeeping Society” and it operated out of big building near Harvard Square. The co-op employed women who were paid to do laundry and bake bread for nearby families, tasks most women had to do on their own and without pay. Producers’ cooperatives — where workers would pool much of their labor and their power — were common, but Peirce’s was the first to take on housework.

Peirce’s co-op lasted for about two years but she never achieved her bigger vision, which was to integrate housework cooperatives into the designs of new housing projects. But other feminists were also getting interested in this idea that so-called “housework” should be removed from the home.

Topolobampo

One of them was Marie Howland, a textile-worker-turned-architect, who was inspired by a cooperative community she spent time at in Guise, France. It was known as the “Social Palace.”

The “Social Palace” was built around an iron foundry and the residents there took turns working in a shared housekeeping program, which included a prepared food service for the 350 workers and their families. And as Howland studied the design of the community, she began to dream up her own utopian society, where a place like the Social Palace was the norm. She even wrote a novel about it when she came back to the U.S.

Marie Howland wasn’t the only person using fiction to dream up an ideal future full of kitchen-less houses. A lot of people were writing futuristic novels — including some books that depicted a feminist future, with shared, cooperative kitchens. In the late 1800s, at least one of those books was a bestseller.

Between popular fiction and a few real-world experiments, the concept of a kitchen-less house was spreading. And in 1874, mill-worker-turned-novelist-and-architect Marie Howland saw her chance to implement some of those ideas. She started working with two men, designers Albert Kimsey Owen and John Deery. They were among the many people in the US at the time who believed that a more harmonious society — one where people lived collectively, and jointly owned all means of production. And in the 1870s, together with Marie Howland, they set out to build a perfect town.

The town was called Topolobampo. And originally, their designs just had single family homes with kitchens. But Marie Howland convinced them to sketch in small groups of kitchen-free houses, each with access to a shared kitchen, where residents would take turns working.

The team made elaborate plans. But ultimately, not a lot of people got to live at Topolobampo. The project ran out of money pretty quickly… before Howland’s kitchenless houses could ever be built. To the male founders, they weren’t a priority.

Food by Train

But the dream wasn’t over. In 1915, another feminist named Alice Constance Austin embarked on another kitchen-less utopian experiment. Together with Job Harriman, a socialist politician, she set out to create a community called Llano del Rio, outside L.A.

Austin thought it could be a city of kitchen-less houses. And she thought that the food could to each house on a system of underground trains. She drew maps upon maps, and tons of floor plans. She published her ideas in a journal called ‘The Western Comrade’ and even applied to patent her underground food train idea.

But like Topolobampo, Llano del Rio also struggled to get enough funding. The male founders once again weren’t that into the idea of the kitchen-less houses, and the community fell apart before they could ever be constructed.

The Dream Lives On

But the kitchen-less house movement still didn’t die. In England, the urban planner Ebenezer Howard actually incorporated kitchen-less homes into some of his “garden city” communities. He called these homes “cooperative quadrangles.” They had a shared courtyard and shared kitchen, surrounded by smaller kitchen-less dwellings.

By the late 19-teens, in the US, the idea of ending the private kitchen was pretty mainstream. Big publications, including the Ladies’ Home Journal — a magazine whose very title literally puts women in the home – ran articles promoting kitchen-less houses. They compared the private kitchen to the private spinning wheel — a relic of the past, and a manifestation of oppressive, unpaid labor that could be done much better on a larger scale.

It was a popular and progressive movement. But, it certainly wasn’t without flaws. Many of these “utopian” movements were led by middle class white women who didn’t appear to seriously embrace the needs and contributions of Black women and women of color, many of whom had been violently forced into caretaking and housekeeping roles for generations — and who were also fighting their own battles for dignity and pay.

In time, the movement for kitchen-less houses faced roadblocks it couldn’t overcome. Inflation hit hard after World War I and people were struggling. Figuring out how to pay for prepared meals in service of women’s liberation just wasn’t a priority for everyone. Plus, more private kitchens meant more customers for electric companies, who aggressively marketed their appliances to women.

Instead of continuing the additional taxing, unpaid work of rallying for a shared drudgery-free future, many women settled for a dishwashing machine.

Interior Revolution

The dream of mainstreaming the kitchen-less house was dying. But the problem of the kitchen remained. And that brings us back to Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky, the Austrian architect from the beginning of our story.

In the 1920s, a young Schütte-Lihotzky took a very different approach to the home kitchen. She didn’t want to eliminate it. She wanted to elevate it, with clever and scientifically informed design. She wanted kitchen work to move with the ease and quickness of a factory, so women could get in and out, and on with their lives beyond the kitchen.

Schütte-Lihotzky was born in Austria in 1897, and as one of the country’s first woman architects, she started working on public housing efforts there when she was barely into her 20s. She worked closely with residents to learn what worked best for them and their lifestyle. And she designed for those who had never been “designed for” on a large scale before; she designed for mothers, but also but for sisters who lived together; or for groups of single women, some of whom had husbands who perhaps didn’t return from war, who lived together in the same building and shared some of the housework responsibilities.

Schütte-Lihotzky’s early work got her noticed by Ernst May, a city planner and modern architect in Frankfurt. He was leading an ambitious government program following World War I to overhaul the way that Germans lived. Because, in the decades after the war, many Germans faced immense shortages of almost everything including food, fuel, and, crucially, housing. In Frankfurt, people were living in old tenement buildings — or sometimes in garden plots. So the government decided to step in with an architectural agenda. It was called the New Frankfurt.

The German government wanted to give a boost to once-booming German industry, and provide housing at the same time. So, for the first time, they encouraged the shells of buildings, and sometimes entire rooms — fixtures and all — to be assembled in a factory by machines, and then set down on the construction site by crane. These new mass produced apartments needed kitchens. So they tapped Schütte-Lihotzky, who was familiar with the needs of women.

When Schütte-Lihotzky arrived in Frankfurt, she got the assignment: design a small, cheap, and marvelously efficient kitchen separate from the living room. There wasn’t much inspiration to draw from — “dining out” culture wasn’t widespread, so there weren’t many professional kitchens. So she studied the kitchens on trains, and in ships.

Based on her studies, Schütte-Lihotzky came up with many thoughtful, practical, and space-saving touches for her kitchen design. Like a Murphy Bed-style fold-down ironing board. Or this thing called the “cook box,” which is kind of like today’s crock pot, except it just used residual heat from the stove to slow cook meats or grains or whatever else — which was a boon considering electricity back then was still really expensive. Or 12 identical measuring cups with spouts that fit into cubby holes in the wall, each labeled with the name of a different grain or foodstuff. Those let you measure without dirtying up multiple cups and dishes.

Based on her studies, Schütte-Lihotzky came up with many thoughtful, practical, and space-saving touches for her kitchen design. Like a Murphy Bed-style fold-down ironing board. Or this thing called the “cook box,” which is kind of like today’s crock pot, except it just used residual heat from the stove to slow cook meats or grains or whatever else — which was a boon considering electricity back then was still really expensive. Or 12 identical measuring cups with spouts that fit into cubby holes in the wall, each labeled with the name of a different grain or foodstuff. Those let you measure without dirtying up multiple cups and dishes.

But perhaps the most revolutionary quality of Schütte-Lihotzky’s kitchen design was how it minimized the physical energy that a “housewife” had to exert. She thought carefully about how taxing domestic work could be, and how to make it as efficient as possible.

That efficiency was, of course, by design. Schütte-Lihotzky was inspired by “scientific management,” a popular idea in the States back in the 1920s. It was mostly applied to factories, where managers would obsessively streamline workflows in order to theoretically maximize their profits.

Schütte-Lihotzky applied those ideas to the kitchen and, in the interest of minimizing work for so-called “housewives,” she did tests to eradicate excess movements. She tracked women’s movements like football plays or complex dance steps, with little lines across the floor, and then streamlined accordingly. Women would be like basketball players holding the ball: never more than a pivot or step away from where they needed to go.

Prefab for the Masses

The Frankfurt Kitchen was “mass produced” in batches of 10-15 or so at a time, with little variations or changes made throughout. And between 1926 and 1930, the prefab kitchen was installed in about 10,000 public housing units in Frankfurt.

Architects and public housing leaders across Europe quickly sang its praises. But in practice, this renowned kitchen didn’t always jive with how people actually wanted to use their kitchen. Sure, there were those complaints that the bin for potatoes was too small. But there were bigger issues. Like the fact that the kitchen was now separate from other living spaces.

That sounds pretty good in theory — leave the drudgery behind when you close the kitchen door. But for many women, household labor was so gendered that they also had kids to take care of! Those joint living room/kitchens of old, with the big open hearths and the slapped-together furniture? They may have been slipshod, but you could have company, or watch the kids, even while you cooked. But now the kitchen was way too small to watch a child in.

Thee city held classes on how to use the Frankfurt Kitchen and its new technologies. They made a silent film as a sort of PR campaign. The complaints about the cordoned-off kitchen didn’t die down — but the German government was adamant that so-called “modernism” was the way of the future. And they kept building Frankfurt Kitchens.

But as the Nazi party rose to power in Germany, a lot of the burgeoning social housing programs were cut. In 1930, the Frankfurt Kitchen was installed for the last time. But despite the fact that some residents hadn’t been crazy about the kitchen, it remained hugely influential.

In the US, everyone from private companies to government agencies were coming up with kitchen designs that looked a lot like Schütte-Lihotzky’s. Like when the Department of Agriculture launched the “Step Saving” kitchen in the late 1940s. Though imitators abounded, Schütte-Lihotzky didn’t always get credit as the mother of the modern kitchen in the decades after she designed it. But as the 50s gave way to the 60s and the 70s, Schütte-Lihotzky and her Frankfurt Kitchen started to get renewed attention from architects and historians.

In 1980, the City of Vienna gave her a big architecture award. But Schütte-Lihotzky’s resurgent popularity opened her ideas up to criticism from some other second-wave feminists who took a harder line against women’s unpaid labor. Activists, including members of a new international movement called Wages for Housework, picked up the unfinished business of 19th and 20th century feminists, arguing that the entire capitalist system would collapse if there was a widespread demand for pay. One vocal leader of the movement would often refer to the work of architectural historian Dolores Hayden — who you heard from earlier — and even called for a return to the shared kitchen efforts of the 19th century.

In 1980, the City of Vienna gave her a big architecture award. But Schütte-Lihotzky’s resurgent popularity opened her ideas up to criticism from some other second-wave feminists who took a harder line against women’s unpaid labor. Activists, including members of a new international movement called Wages for Housework, picked up the unfinished business of 19th and 20th century feminists, arguing that the entire capitalist system would collapse if there was a widespread demand for pay. One vocal leader of the movement would often refer to the work of architectural historian Dolores Hayden — who you heard from earlier — and even called for a return to the shared kitchen efforts of the 19th century.

Others came to have critiques specific to the Frankfurt Kitchen itself — critiques that get to the heart of its ambiguous legacy. All of those glorious, handy doodads — the fold-down ironing board, the 12 identical, easy-to-access aluminum measuring cups, the modern stove and oven — they may have been placed efficiently… but that efficiency was a bit of a trap. Because it made it possible to do so much more. Sure, it may only take four seconds to fold your ironing board up into your wall. But now you have an omnipresent ironing board in the kitchen. And you’re expected to press your napkins. Who does that?

So, was Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky’s design really so radical? She absolutely wanted to lessen the burden of housework for women. But the legacy of the Frankfurt kitchen is pretty murky. And towards the end of her life, even Schütte-Lihotzky herself came to turn her back on this kitchen she designed before she even turned 30.

Women’s Work

But there’s another side of this story. Because, you can intellectualize the kitchen until the watched pot boils. But the thing is, a lot of us, regardless of gender, love our kitchens. It has an appeal. Every party ever somehow finds all attendees crammed into the kitchen. Kitchens are hallowed grounds. Because kitchens… are where food is.

A lot of the knowledge that women have about food is rooted in oppression. A history of sexism, as well as slavery and indentured service, have meant that the burden of that unpaid kitchen work has fallen to women, and especially to Black women and women of color. But, to people like Kayla Stewart — a food and travel journalist who writes primarily about African American foodways — not celebrating and valuing that knowledge… is an insult to injury. Because the home kitchen can also be a classroom, a place to connect with loved ones and family, and culture. To her, the issue is more about whether or not women have a choice to be in the kitchen.

Yes, design matters. But a few less trips across the kitchen is not what’s going to fix the great discrepancies in care work.

That takes a whole system — a system that not only respects and values the contributions of home cooks, but also offers affordable food options if we don’t want to cook — and things like school meals, and jobs that leave us with energy so that cooking can be fun. If those things were in place, any number of kitchen layouts could be empowering. From Schütte-Lihotzky’s lightning fast, bite-sized design, to Alice Constance Austin’s utopian collective kitchens.

Leave a Comment

Share