The Fabric of Life by Kurt Kohlstedt

A while back, Kurt Kohlstedt was researching a story about sackcloth dresses, a type of DIY clothing made from upcycled feed and flour sacks. The topic seemed somehow familiar, though, so he decided to call up a historian who might have told him about it — his mother.

Sally Gregory Kohlstedt is a history professor at the University of Minnesota who teaches courses on science and American culture as well as women and gender in science. She was born in Michigan during World War II. Her dad was working in Detroit at the time, then shipped overseas. So she and her mother went to live with her mother’s parents (Sally’s grandparents) on a rural farm in the “thumb” of the state — an eastern section sticking up into Lake Huron. And like other places in America, people in that region developed ways to deal with shortages, especially in the late 1920s and through the war.

Sally Gregory Kohlstedt is a history professor at the University of Minnesota who teaches courses on science and American culture as well as women and gender in science. She was born in Michigan during World War II. Her dad was working in Detroit at the time, then shipped overseas. So she and her mother went to live with her mother’s parents (Sally’s grandparents) on a rural farm in the “thumb” of the state — an eastern section sticking up into Lake Huron. And like other places in America, people in that region developed ways to deal with shortages, especially in the late 1920s and through the war.

“When I was a little girl,” she explains, “my grandmother did most of the sewing for all of us and so the fabric that she used for what we called our ‘everyday dress’ was actually fabric that she would pick out by going to the local general store.” Her grandmother would buy sacks of flour, and then reuse the sacks. It was a “fairly decent quality fabric” — it had to be finely woven to hold the flour. And the sacks were huge, she says, “as big as I was because they had to hold 50 or 100 pounds of flour,” not like the small five- or ten-pound paper bags we have today.

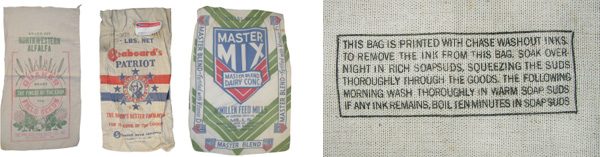

Her grandmother and the women of that community would bake their own bread, pies and cookies, and they used a lot of flour. Some of the sacks they got were plain or had company logos designed to be washed back out so the fabric could be made white again.

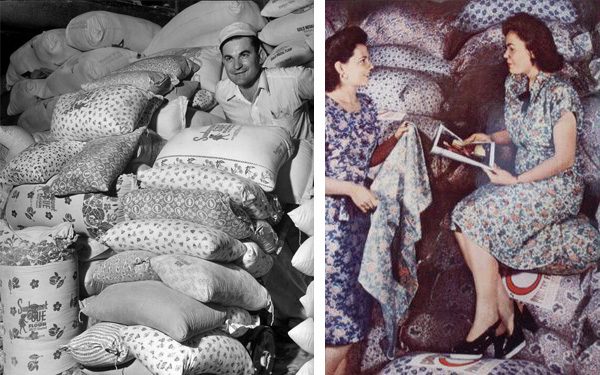

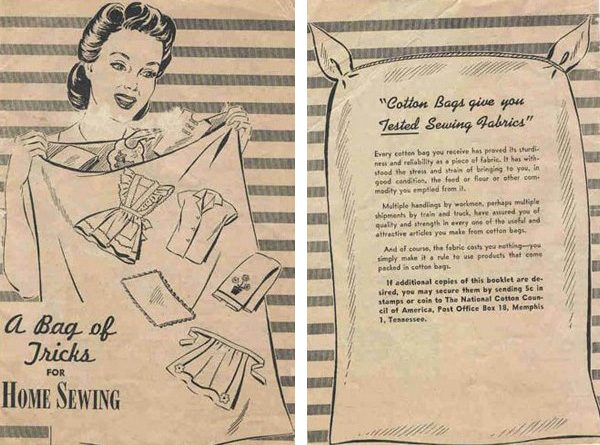

But as companies caught onto this sack fabric trend, they realized they could boost their sales by using nicer cotton and designing fresh and fashionable patterns for their sacks. Some manufacturers even sponsored national sackcloth dress-making competitions.

Over time, a lot of flour sacks came to be covered with different kinds of patterns and colors, which her grandmother picked out carefully at the store. “She learned quickly that I didn’t like pink,” recalls Sally. “So she avoided getting me pink fabric or pink flowers on fabric.”

People at the time also turned sacks into quilts, curtains, even diapers. And farmers reused livestock “feed bags” too. The fabric was rougher, but it still worked for things like towels. Sally’s “first sewing experience was taking a piece of that fabric and hemming it so that we could use it for dish towels.” And her grandfather had an apron made by her grandmother for doing really dirty work — too dirty for “work clothes” — like helping to birth calves, which was a “pretty bloody mess.”

Intending no pun, Sally aptly described this phenomenon as part of the “fabric of life” for people living in rural America at the time. These weren’t just about necessity, but also became about fashion and identity. Often, people could tell who was from what family just by looking because they all wore outfits made from the same patterns. Sally remembers sometimes getting “to go to a fabric store and buy velvet or wool or linen. But woven into ordinary life in these farm communities was going to the general store and picking your fabric.”

Comments (13)

Share

My favorite image of the flour sack prints is from Life Magazine. In the image there is a pile of Sunbonnet Sue flour sacks in assorted prints, but the worker is filling one with a stuffed bunny sewing pattern on it. I like to think that even in times of scarcity and rationing that someone’s little girl, who came with her mother to the general store pleaded for that flour sack like my little girl asks for stuffed animals… well everywhere. I hope she got it.

Ice wasn’t the only material they experimented with for shipbuilding in WWII. Look up the concrete ships. There’s the wreck of one just off a beach in NJ.

The story of the Stroh violin was fascinating especially as it has a strange connection for me. I am from Northern Ireland and in the capital city, Belfast, there is a well known Romanian busker that uses what I now know to be a Romanian horn violin. This morning I was talking to my work colleagues about the busker, wondering what the strange instrument was. A couple of hours later I listened to this podcast and to my amazement, I could not believe that this podcast contained the answer to our earlier conversation and that the instrument was one of the subjects in the podcast! I just cant believe it, what are the chances!

I’m a big fan of the show and never miss a podcast, I particularly like these mini stories episodes, especially when you come up with fascinating and interconnected stories like this!

I wish the web article had more about the city flag redesigns.

Yes, I came to the site for the same reason, hoping to see the old and new flags!

Might want to check this out! https://99percentinvisible.org/article/vexillology-revisited-fixing-worst-civic-flag-designs-america/

I once found a portal into an interdimensional vomitorium when visiting Pocatello. I saw some unexplainable entities there who were really into eating pawpaws.

Best episode all season

Hey, I love the Habbakuk story, although I wonder if your piece on it was summarized from a CBC Radio story of a few years ago? It would be nice to at least provide a link to that much longer radio doc, which goes into a lot more detail on the work of Geoffrey Pyke:

http://www.cbc.ca/radio/ideas/iceberg-ship-habbakuk-1.2914235

Myth-Busters also did an episode on pyke-crete:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UMKis4FPykw

Great story!!! Funny fact I round researching this story: the man who patented the idea was named ‘Bales’. :) There are some really good books about this, including one called ‘Feedsack Secrets’. Question: is anything known about the designers of the patterns?

The admiral who came up with the ship idea was named Mountbatten. Was he in any way related to Prince Philip? I was just wondering. Thanks!

Sheila… yes, as an Englishwoman, I was somewhat irritated by “some guy called”. How would an American like it if I said “some guy called Sherman”?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Louis_Mountbatten,_1st_Earl_Mountbatten_of_Burma

More cheerfully, I saw a horn violin on stage at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford last year. Sadly, I can’t work out how to put a picture on here.

I was (even as an American) a bit vexed when a member of Prince Phillip’s family and mentor to Prince Charles was only described as this one admiral. There was even the loss of an additional mini story in the deal. Mountbatten was a design choice to Anglicize a Germanic name (maybe a bit of a stretch), the name was chosen to obfuscate the family’s German heritage during WWI by translating the parts of the name separately and smashing them back together.