The Cassette tape was great in so many ways, but let’s be honest, they never really sounded great. But because the cassette was so much cheaper and easier to use and portable, a lot of people didn’t care so much about the audio quality. They just wanted to be able to use something that they could carry around with them.

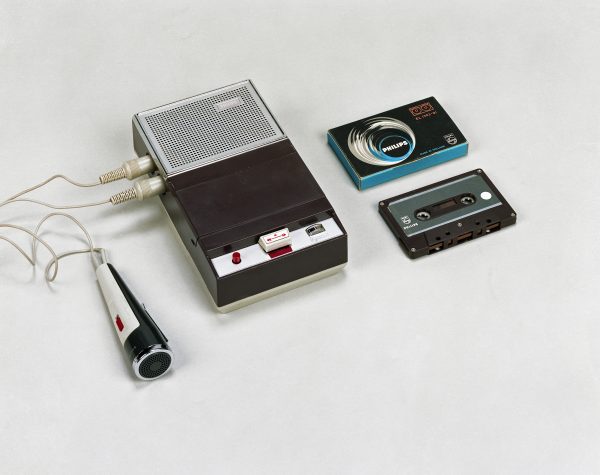

Cassettes weren’t meant to be as high-fidelity vinyl or reel-to-reels. They was meant to travel where those other formats couldn’t. The cassette’s other big advantage: it was easy to record on.

Cassettes weren’t meant to be as high-fidelity vinyl or reel-to-reels. They was meant to travel where those other formats couldn’t. The cassette’s other big advantage: it was easy to record on.

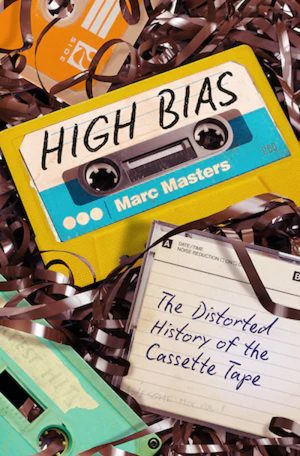

We talked to Marc Masters about his new book High Bias, about the history of the cassette. One chapter about concert bootleggers covers perhaps the greatest success story of the cassette: Grateful Dead live tapes.

Dead & Tapes

The Grateful Dead expanded out from a Bay Area staple into a nationally touring must-see live act. They became a focal point for the counterculture. Their shows were never the same twice. They would make up the set list as they went, linking songs together with extended improvisations.

The magic of their live shows didn’t quite translate into their studio albums. They released a few official live albums that were closer to the experience, but it simply wasn’t enough. Fans wanted to hear every show. Intrepid fans would sneak in their own tape recorders and microphones, to try and capture the elusive raw magic.

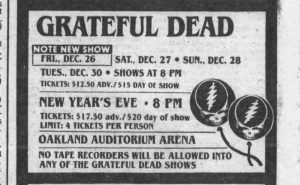

In those early days, illegal bootlegging was a widespread concern in the music industry. And at first, the band was opposed. Their crew would confiscate the tapes, or even snip their cables. But the taping quickly became so widespread that the band grudgingly accepted reality.

New York tapers formed clubs to trade recordings. They were the first to establish an important principle: the tapes couldn’t be sold for profit. You had to either swap for another tape, or simply give it away. The music was a communal resource to be shared freely. Once it became clear that people were taping to listen, not profit, the band decided to more or less look the other way.

Grave New World

Early tapers were still mostly using bulky reel-to-reels. When the tape ended, you had to unspool the whole reel to switch tapes. It was a difficult and time-consuming process to do mid-set.

The earliest cassette recorders were still mono and lower-fidelity. But throughout the 1970s, new higher-fidelity portable cassette decks were released, made by brands like Nakamichi and Sony. Some even came with microphones. Taping became more and more accessible. Cassette decks had widely replaced 8-tracks in cars. So as you drove from one show to the next, you could listen to your Dead tapes the entire way.

There are two main types of Dead tape, which you can hear in our story: Soundboard tapes were mixed off of the onstage microphones, and are tight, dry and clear, with almost no crowd sound. These were made by the road crew, mainly for the band’s archives, but would occasionally leak out. Audience tapes were more common have less clarity, but you get more overall blend of the band, the room sound, and the crowd.

These tapes would get copied over and over. People would have dubbing parties where they’d all each bring a tape recorder and they’d chain them all together. Later, dual-deck cassette recorders could make copies without needing a second machine.

But every time you made a copy, you would reduce the fidelity of the tape further and further. The sound degrades a bit more every time, and the tape hiss multiplies.

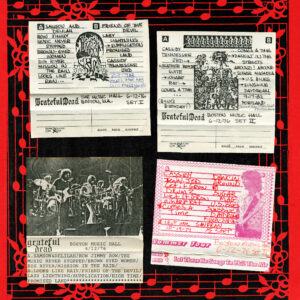

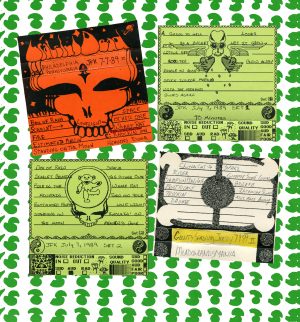

But true believers didn’t let that stop them. Diehard fans didn’t just listen to the music. They collected it, organized and cataloged it. Labeling cassettes became an art unto itself. Fan magazines published setlists, and had classified sections: taper seeks tape.

Fast-forward to the early 80s. Cassette sales had finally overtaken vinyl. The newly-introduced Walkman created the power to soundtrack your life at all times.

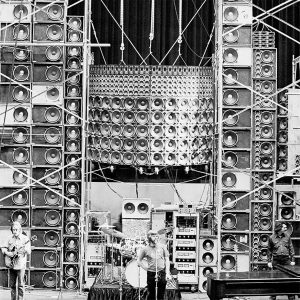

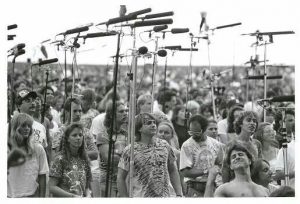

Meanwhile, The Dead had graduated to stadiums. They chose to fully focus on touring, and went seven years without releasing a studio album. Even casual fans were mainly listening to the tapes – that was the only place to hear the new songs. Taping had become their own subculture. Forests of microphone stands would stick up above the crowd.

The problem was… some of these tapers were driving other fans nuts. So in October 1984, the Dead set up an official taper’s section. Tapers would buy special tickets to sit behind their longtime sound engineer Dan Healy.

At that point, the band’s finances were dire. For their entire career, they’d struggled to break even. Their ticket sales were massive, but just barely covered their enormous overhead.

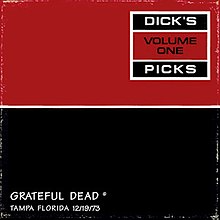

So, they started considering their tape vault as a potential source of income, and hired a prolific tape collector to help them sift through the archives. In 1993, they released the first of the Dick’s Picks CDs – the greatest soundboard tapes, as selected by Dick (and later, his successor David Lemieux and Dave’s Picks.)

So, they started considering their tape vault as a potential source of income, and hired a prolific tape collector to help them sift through the archives. In 1993, they released the first of the Dick’s Picks CDs – the greatest soundboard tapes, as selected by Dick (and later, his successor David Lemieux and Dave’s Picks.)

Nights of the Living CDs

By 1991, CDs replaced cassettes as the most popular format. Many tapers had also switched to digital recorders. But those were much more expensive, and CD-R burners cost thousands of dollars at the time. The easiest way to share was still: the cassette.

After Jerry Garcia’s death in 1995, the band split up, but Dead tapes continued to circulate. Similar taping networks sprung up around other bands, as well as Dead members’ subsequent offshoots and solo projects.

In the early 2000s, fans embarked on a collective project to digitize and organize the recordings, which found a home on archive.org. Deadheads no longer had to cultivate their own personal libraries or track down rare recordings themselves. With one click, they could pull up virtually any moment from the Dead’s entire history. And if they had a tape that was missing, they could share it with the rest of the fandom.

Bonus Links and Resources

Marc Masters’ High Bias: The Distorted History of the Cassette Tape

Dead Links

- Sophie Haigney’s articles on Dead shows, parts one, two and three

- Mark Rodriguez’s book, which has lavish photos from his collection of some thirteen thousand Dead cassettes

- Jesse Jarnow helped us edit this story; his book Heads is a definitive resource on the psychedelic counter-culture. He also co-produces the official Grateful Deadcast.

- See also: John Brackett’s book Live Dead, part of Duke University Press’s upcoming series on the Dead.

- Owsley Stanley interview by David Gans.

Where to Start, for the Dead-Curious

- Grateful Dead Sirius XM channel

- Most people start with Cornell ‘77, perhaps their most famous show

- Jesse Jarnow edited a Pitchfork article with songs recommended by a panel of Dead experts

Suggested tapes:

- 09/03/67 – Dance Hall, Rio Nido, CA

- 09/02/68 – Betty Nelson’s Organic Raspberry Farm, Sultan, WA

- 02/28/69 – Fillmore West, San Francisco, CA

- 05/02/70 – Harpur College, Binghamton, NY

- 04/28/71 – Fillmore East, New York, NY

- 8/27/72 – Old Renaissance Faire Grounds, Veneta, OR

- 10/25/73 – Dane County Coliseum, Madison, WI

- 09/11/74 – Alexandra Palace, London, England

- 08/13/75 – Great American Music Hall, San Francisco, CA

- 07/17/76 – Orpheum Theater, San Francisco, CA

- 11/05/77 – Community War Memorial Auditorium, Rochester, NY

- 11/24/78 – Capitol Theater, Passaic, NJ

- 12/26/79 – Oakland Auditorium Arena, Oakland, CA

Other Shows in This Episode

- The first ever Grateful Dead tape, from the 01/08/66 Acid Test

- Tour manager Sam Culter busting a taper at the 05/16/70 show

- 08/06/71 Hollywood Palladium – Bob and Phil razzing a taper

- “Samson and Delilah” from 11/30/80 Fox Theater

- Final Dead & Co show on 07/16/23

Leave a Comment

Share