This past May, the city of Los Angeles rolled out a brand new, state-of-the art feature for bus shelters. It’s called La Sombrita. La Sombrita is a metal screen that’s intended to provide shade for the thousands of people who ride the bus every day. The shade screen is about two feet wide, ten feet tall, and it kinda looks like a curved teal metal surfboard filled with tiny holes. Right away, Angelinos were not happy. This heated conversation got us thinking about our interview with Sam Bloch about inequality and shade and we asked Sam back to get thoughts about La Sombrita, and whether the controversial shade sail could actually be a good thing for shade-starved Angelinos.

Since our original conversation, Sam Bloch has begun writing a book about shade, and he wants to speak with our listeners. If you have stories about how shade has impacted your life, send a note to Sam at sambloch.com or [email protected].

Journalist Sam Bloch used to live in Los Angeles. And while lots of people move to LA for the sun and the hot temperatures, Bloch noticed a real dark side to this idyllic weather: in many neighborhoods of the city, there’s almost no shade. He was surprised to find people awkwardly huddled behind telephone poles to get relief from the glaring sunlight. “I noticed people waiting behind the people waiting behind telephone poles because there’s only that small sliver of shade,” says Bloch.

Shade can literally be a matter of life and death. Los Angeles, like most cities around the world, is heating up. And in dry, arid environments like LA, shade is perhaps the most important factor influencing human comfort, “even more than our temperature, more than humidity, more than wind speed,” says Bloch. Without shade, the chance of mortality, illness, and heatstroke can go way up. People become dizzy, disoriented, confused, lethargic, and dehydrated — and for the elderly or people with health issues, that can tip into more dangerous territory, like heart attacks or organ failure. Shade can literally save lives.

Public Shelter

There are lots of factors working against shade coverage in Los Angeles. The biggest might be the city’s lack of consistent tree canopy. From outer space, it’s clear that LA has a big tree disparity, with many green neighborhoods, and many completely exposed to the sun.

Los Angeles is also notoriously anti-density. “Sunlight and open space is a part of the culture, but it becomes a problem for people who can’t escape it,” says Bloch. There are relatively few tall buildings and they’re spaced far apart from one another or located in certain height districts—Downtown LA being one of them, leaving other parts of LA without the shade that tall buildings provide.

Los Angeles wasn’t always like this. If you look at photos of LA from 150 years ago, it’s mostly grasslands. When LA was settled by the Spanish, the city’s design was governed by a rule called the Law of the Indies, which meant the city’s layout roughly conformed to a 45-degree angle, ensuring sunlight in the winter and shade in the summer.

The influence of Spanish architecture meant that early development in Los Angeles included a lot of missions and adobes with internal courtyards that are shaded, and covered walkways, or paseos, which provided relief from the sun before air conditioning.

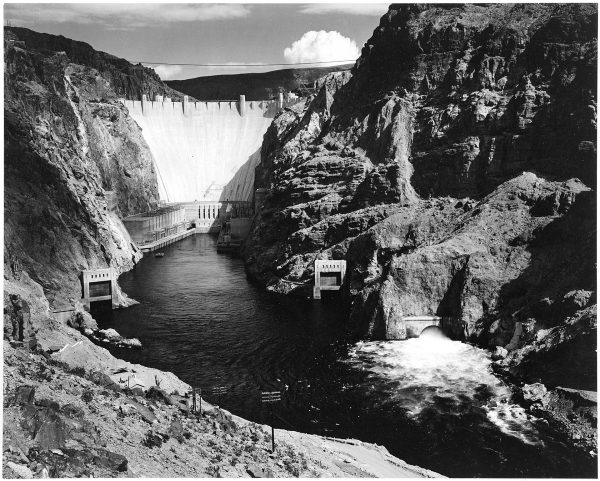

Hot Dam

But things changed drastically in LA after the advent of cheap electricity and the completion of the Hoover Dam. The city rebuilt itself around controlled air conditioning and car culture. Palm trees became an LA calling card. “As Mary Pickford said, [palm trees are] very good for window shopping from the seat of your car because the tree trunks aren’t that robust,” notes Bloch, but they’re also “as one essayist said, about as useful for shade as a telephone pole.”

Wealth of Shade

Today, in Los Angeles, shade is distributed to people who can afford it. If you go into neighborhoods that were designed to be wealthy residential enclaves, the sidewalks are wider and include strips of grass four to ten feet wide, for the easy planting of thick, leafy trees.

Hancock Park, for example, is a flat neighborhood, landlocked in the center of the city. There is nothing about it that naturally lends itself over to being a lush, verdant tree canopy. But the neighborhood was developed as an exclusive, wealthy residential enclave. And when that happened, the power lines were moved underground and the layout was designed specifically to allow for tree growth. This is not the case for other large residential areas across Los Angeles.

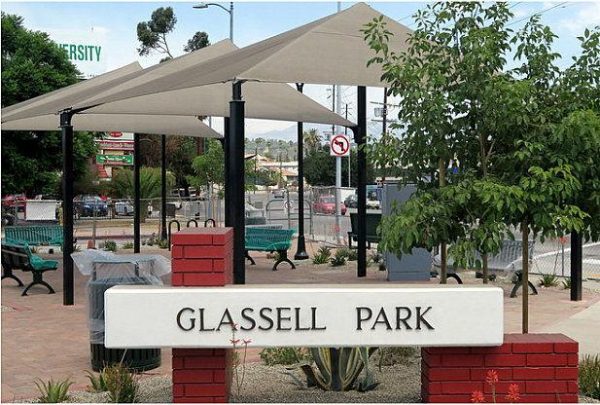

There have been efforts to add more shade, especially around bus shelters, but it’s been difficult, says Bloch, “because shade is a tripwire.” In the instance of the Glassell Park Transit Island, a concerned neighborhood resident wanted to put up a simple bus shelter over a space where she saw people congregating. She ended up working with an architect to erect shade sails at the transit island. This seemingly easy development became very complicated. The new structure had to be consistent with the regulations of the Americans with Disabilities Act which meant adding curb cuts to make the sidewalk wheelchair accessible. It also meant expensive changes to underground water-mains and power lines. “You have to take care of all these other things before you can decide to do this very lightweight sort of low-res fix,” notes Bloch.

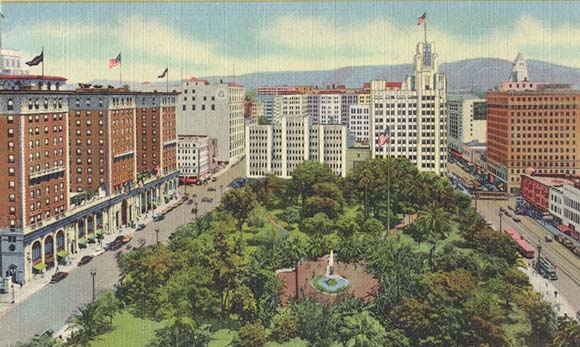

Perishing Shade

But the sidewalk isn’t the only place where LA has a shade problem. The public parks also provide very little refuge from the hot sun. Pershing Square, for example, used to be full of shade trees. But after a new underground parking structure destroyed the root system, the thick, dense tree canopy was replaced. Other parks lack trees because of a strategy Bloch has reported on called crime prevention through environmental design. In LA, there is an idea that increased visibility in public spaces will lead to higher levels of public safety. In several instances, it’s believed the LAPD has installed pole cameras in parks or in public housing projects and cut down mature trees to give the camera a clear sightline.

Informal Shade

There have been a number of informal interventions to create shade across the city, particularly in Latino neighborhoods. James Rojas is an urbanist who writes about Latino urbanism, and leads a walking tour around Los Angeles where he makes note of tarps and DIY shade sails that have been connected between garages or hung up in alleyways to provide some public shade. These types of interventions are tolerated in private spaces, but as soon as they step into the public sidewalk, things become more complicated. Los Angeles processes 16,000 charges every year for obstructions of public space, a major deterrent to grassroots urbanism.

This episode includes an interview with Sam Bloch, about his article Shade which originally appeared in Places Journal.

Leave a Comment

Share