Houseplants are having a moment right now. In 2020, 66% of people in the US owned at least one plant, and sales have skyrocketed during the pandemic. Meanwhile, Instagram accounts like House Plant Club have a million followers. Over the past decade there has been a steady stream of think pieces offering explanations for the emergence of this new obsession. But while millennials may have perfected the art of plant parenting, this is not the first time people have gotten completely obsessed with houseplants. Journalist Anne Helen Petersen digs into the history of domesticated plants in a series of articles on her Substack, Culture Study, and joins us to talk about what she’s found.

Humans have been growing plants indoors for a long time, especially herbs and flowers. Ancient Egyptian, Greek, and Middle Eastern societies all had potted plants. The Chinese were growing ornamental plants indoors as far back as 1000 BC. But the rise of the global houseplant economy that we are familiar with today, really begins during the age of European imperialism. During the Enlightenment era, and European scientists were obsessed with cataloging and collecting all of the new species they encountered. Such plants were called “exoticks,” and the European public flocked to botanical gardens to marvel at all of these strange new species they had never seen before.

Botanical gardens also provided an opportunity for European people to see what the natural world might have looked like in the colonies. They were almost like imperial theme parks, and growing these tropical plants in Europe was a demonstration of conquest and control. And as indoor plants became fashionable status symbols, the desire to have one’s very own conservatory filtered down to the middle classes. Indoor plants got more and more popular in the Victorian period, until they eventually outgrew the conservatory and moved inside the house. They went from being extras outside the home to becoming interior design staples.

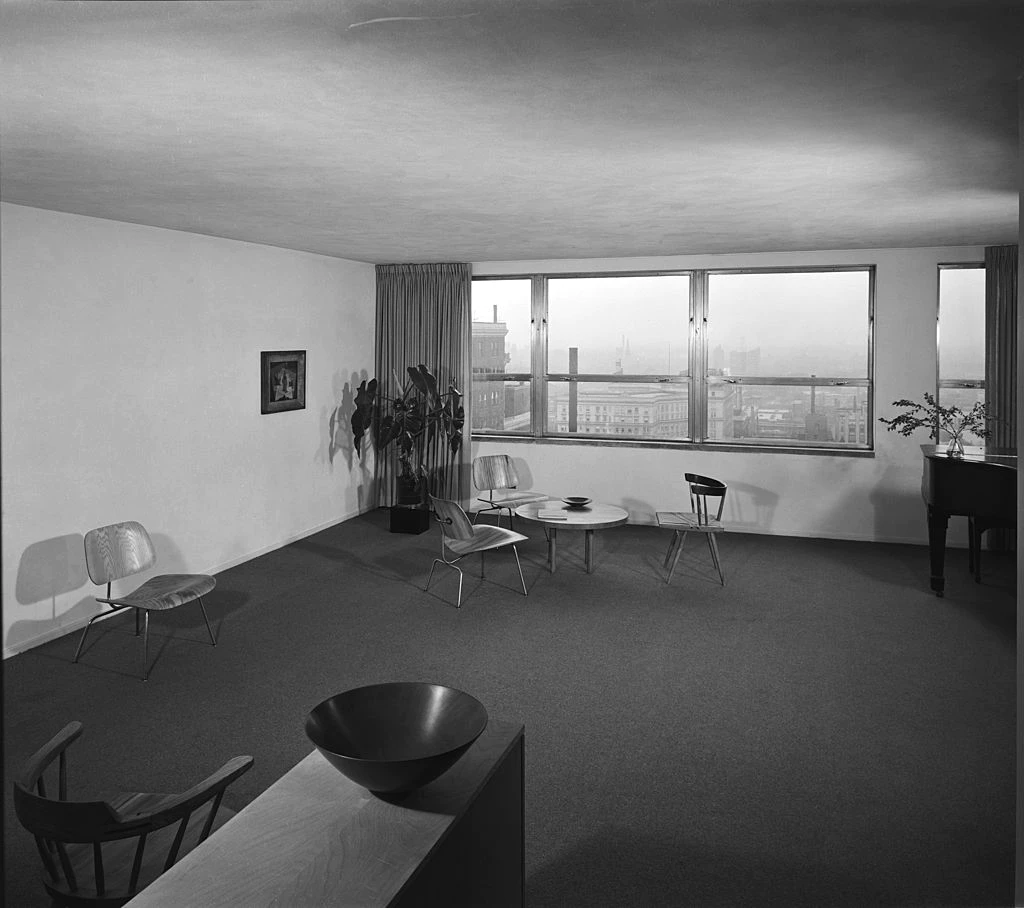

With the arrival of Modernism’s stark and elemental geometries, houseplants (and decor in general) took a backseat to architectural elements. Popular houseplants during this period included the famously sculptural monstera deliciosa, the rubber plant with its thick shiny leaves, and, perhaps the most modernist plant of all, the cactus.

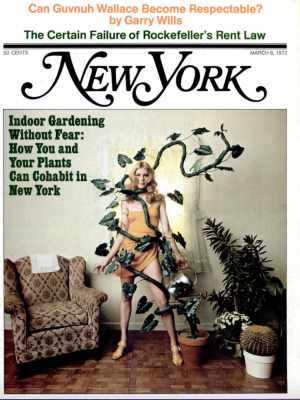

But if modernism was a relative ebb in our relationship with indoor plants, by the 1960s and 70s homes were once again awash in green. Like the Victorian era, the house plant wave of the 60s and 70s was driven in part by a feeling that people had lost touch with nature. This was the dawn of the modern environmental movement and the back to the land movement. People longed to reconnect with the natural world.

The most recent return of the houseplant boom dates back to the early 2010s, give or take, fueled by a variety of factors — more people living in small urban spaces, increasing affordability of plants, and, of course, social media sites like Instagram where visuals rule the feeds.

Since the early days of European colonization, house plants have become commodities sold on a global marketplace. And at this point there is a certain placelessness to them. Today, you might encounter the same house plant at a coffee shop in Tokyo or a hotel in Mexico City, or on social media. And then you can go online and order that same plant for yourself, and it will appear on your doorstep in a couple of days. Collecting house plants has gotten so easy that you can lose track of the fact that these objects of interior design are also living organisms from a particular place. And each one has a history.

Click to check out more work by writer Anne Helen Peterson. Also be sure to tune into PlantWave to listen to the music of plants.

Comments (2)

Share

What was the Instagram of the person who danced with plants? Thank you! :)

This is the best name for an episode ever. 😂😂😂