Back in the mid-1950s, Stephen Chen attended a primary school called Buckingham in Cambridge Massachusetts, right by the Charles River. Every spring, their school had a fair called The Buckingham Circus, with games and activities for the students. Parents would put on a bake sale, showing off their dishes. One year, Stephen’s mother Joyce Chen decided to bring in a Westernized version of egg rolls. Stephen and his sister were the only two Asian kids at the school and the family thought it would be nice to bring in something that showed off their culture. Those eggrolls became a hit and launched an incredibly successful career for Joyce as a chef and television host.

By the early 70s, Joyce Chen was flourishing as an entrepreneur and a celebrity in the cooking world. James Beard recognized her as one of the best when it came to Chinese cuisine. She was even put on a US postage stamp. In 1982, she launched Joyce Chen Specialty Foods, a line of Chinese cooking sauces made with high-quality ingredients. Products like duck sauce, soy sauce, hoisin, and sesame oil were all bottled and labeled with Joyce’s name, and shipped to the grocery stores across the country. The supermarket was a different arena for Joyce. She didn’t have much say over how or where their products were displayed. She put her precious namesake into the store’s hands. Joyce Chen’s sauces were placed in a section that’s come to be known as the “ethnic food” aisle.

It’s a Small World After All

If you’ve ever been to a supermarket in the US, you’ve probably seen an ethnic food aisle. Maybe it was called the “international aisle,” or “world foods,” but it was the same idea. This is the “It’s A Small World After All” part of the shopping experience. It’s where you’ll find ramen next to coconut milk, next to plantain chips next to harissa. Although ethnic aisles look different in every supermarket, they’re often variations on the same theme. And while so-called “ethnic food brands” get a chance to feed the American masses, they’re still confined to the ethnic aisle. And they may never leave.

It wasn’t always like this. The ethnic aisle has been evolving quietly, over the past 100 years. When nationally-owned grocery store chains sprang up in the 1920s and 30s, they were the first to offer customers self-service grocery shopping with produce, fresh meat, and dry goods all under one roof. But most of these stores operated with one specific clientele in mind: white middle and upper-class housewives.

Supermarkets rapidly spread across the country, but there was a clear divide. European immigrants in cities like Boston, Chicago, and New York, shopped elsewhere. “There’s almost two kinds of stores,” says Krishnendu Ray, professor of Nutrition and Food Studies at New York University, “They had the standard grocery store where mostly Anglo American Germanic groceries dominate. And you have stores which are Italian, which are Jews, and Greek tastes.” He says these stores which were run by immigrant entrepreneurs sold the products that their communities liked to eat. These products included things like olive oil, salad greens, or hunks of Parmegiano Reggiano and were not common in grocery stores. The truth was that most of the Anglo-American population didn’t care for Italian food. Olive oil, for example, was described as “greasy, smelly, and bitter.”

But over the decades, that perception began to change ever so slightly. Americans started to eat more and more Italian dishes. Housewives were getting excited about Italian foods, and mainstream supermarkets obliged. Stores began to stock a small amount of imported Italian products, like canned tomatoes, or ingredients for spaghetti and meatballs. But products like olive oil didn’t just get added to the section where the other oils live. Krishnendu says that Italian products were considered “ethnic”. That is, not white, but more foreign and unfamiliar to Americans. Yes, even things like pizza.

Specialty Foods

Around the 1950s Italian products were given their own little corner of the store, intended for unconventional cuisines at the time, these corners were called “specialty foods. But around the late 1960s, the “specialty section” really started expanding. That’s when foreign foods from outside of Europe became very, very popular. Those small specialty sections got bigger and became more of a fixture in supermarkets. And that’s because American tastes were changing fast. For one thing, US soldiers were returning from the Vietnam War, where they had eaten Southeast Asian food. “It is almost like if you have the military presence there and if you are exposed to the local food, you will develop a taste for it, and when they return home, they expect this kind of food,” says Ray.

The biggest game-changer was that the US had recently eased immigration restrictions for the first time in more than four decades. Millions arrived each year. Most were from Latin America, Asia, and Africa, with only a small chunk from Europe. Through the 1970s, supermarkets were in a frenzy, trying to introduce foreign products into their stores. Some American entrepreneurs wanted in. They launched domestically-produced versions of these international foods, salted and corn syrup-ed just right, for the American palate.

The “eTHnIC” AiSLe

As these brands were added to the specialty aisles, that section morphed into something new: the “ethnic” aisle. To promote their products, companies began to use these ethnic aisles in ways that were quite different from other parts of the store. In this section, global flavors were showcased as “exotic”. One of the biggest producers to do this was an American brand named after a city in southwest China called Chun King.

Chun King was a Chinese food company founded by businessman Jeno Paulucci. Jeno was not Chinese, but an Italian-American from Minnesota. He started a line of canned Chinese ingredients a few decades earlier. And by the 60s, he’d perfected a marketing strategy. Chun King products were based on dishes that non-Chinese people loved to order at Chinese restaurants. Except with these all you needed was a can opener. Chun King swept the nation. It was a staple of American supermarkets. But Jeno was a white man profiting off of Chinese food, and he got there by using gross stereotypes and orientalist ideas of the far east. Chun King created displays where shoppers had to squat under bamboo awnings to get to their canned chow mein. He asked employees to wear rice paddy hats while handing out samples. Jeno made shopping for Chun King into an immersive “exotic” experience.

More and more nationalities found their foods squeezed side by side, onto the ethnic food aisle. There’d be Cinco de Mayo displays next to promotions for Eid or the Lunar New Year. With that, it became standard for supermarkets to organize the food of the world in this way, EPCOT style.

It’s Not About Aptitude, It’s the Way You’re Viewed…

So It’s Very Shrewd to be: Very, Very Popular Like Me!

However, not all food nationalities are treated equally. One cuisine, in particular, was able to wiggle loose of its reputation. The major foods on the aisle were Chinese, Mexican, and Italian. But this changed in the 1980s because Italian food got reinvented. Krishnendu Ray links this to a change in how Italians were perceived in the US, as they went from mostly a poor population to an upwardly mobile one. “As poor Italians stop coming in and Italians climb in terms of political office, in terms of filmmakers, in terms of winemakers in Napa Valley, the prestige of Italian culture goes up and Italy emerges as a major economic power and a center for design culture,” says Ray.

An item can get so popular that grocery stores want to make it as easy to find as possible. We’ve seen this happen fairly recently with Huy Fong Sriracha sauce. This Thai sauce, sold by a Vietnamese immigrant, went mainstream after blowing up amongst the hipster food truck crowd in 2009. Foodies loved it. It’s slightly sweet, and spicy – but not too spicy. And its iconic crowing rooster logo graces countless things, from baby onesies to throw pillows. Nothing moves something off the ethnic aisle faster than a bout of extreme popularity.

Some food producers think it shouldn’t be that difficult to leave the ethnic aisle. Aruna Lee is the founder of the brand Volcano Kimchi in San Francisco. The question of categorization has been on her mind as she looks for ways to promote her products. In the next year, she plans on selling the Korean chili paste, gochujang. She hopes it gets shelved next to hot sauces in the store, instead of in the ethnic aisle. She thinks that putting her products in different parts of the store will expose them to new buyers who aren’t necessarily looking for them.

Aruna isn’t the only one who feels this way. Small companies that make products like Indian pickle, salsa, or canned jackfruits, would love a chance at being spotted by shoppers who aren’t going down the ethnic aisle. And honestly, that might look like abolishing the ethnic food aisles, all together.

The Planogram

Errol Schweizer is a former Whole Foods executive and now advises food companies. He has long wanted to do away with the practice of putting all “international food” on a single aisle. He hoped to shake things up when he worked at Whole Foods. He tried to integrate some of the ethnic products with “non-ethnic” products, on other shelves. But he says giant stores like Whole Foods can be hard to change. That’s because the way we shop, and the way stores organize food are all locked in by this one big, complicated system called the planogram.

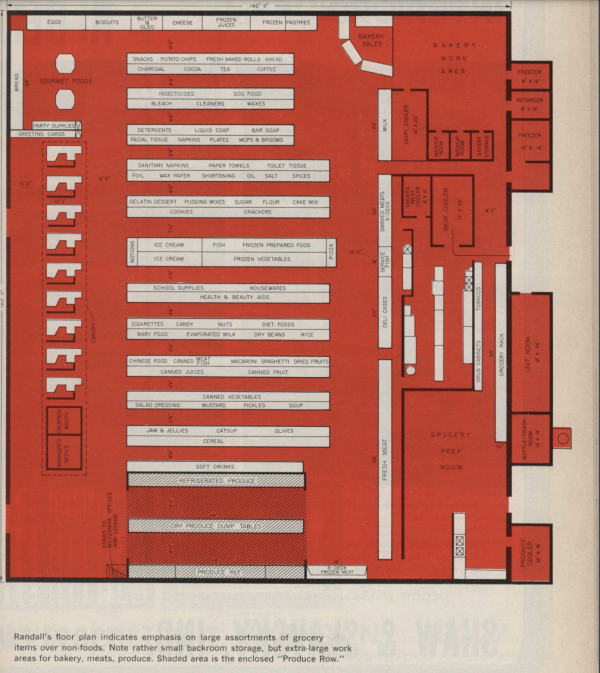

A planogram is essentially a picture with a lot of data. U.S. supermarkets have on average over forty thousand items in store. Not only do managers have to keep track of everything they also have to figure out where to place an item based on where it will sell the quickest. It’s extremely complex, and there’s a lot of money at stake.

Using these planograms, supermarkets have every single inch, every single aisle and wall planned down to a tee. From the expensive so-called “beachfront property” near the cash registers to the special displays at the end of the aisles. No placement is arbitrary. If a bottle of ranch or bag of potato chips goes somewhere, there has to be a strong economic reason behind it. Some shelves get more attention than others. The phrase “eye-level is buy level” exists because things that are placed right in the customer’s line of sight are most likely to sell.

This gets sticky when it comes to introducing less popular products. Say you wanted to put Korean BBQ sauce next to other barbeque sauces, on the condiment aisle, which is one of these attention-getting areas. A planogram would tell a store manager that putting the less familiar, “ethnic” Korean sauce on premium supermarket shelf real estate would be a waste of that space. Because an item like Hellmann’s mayo or Heinz Ketchup would just sell ten to twenty times better. To make the calculation even fussier, supermarkets work with some of the biggest brands on the shelf, to make planograms. Brands like Coca Cola, Nestlé or Frito Lay. These brands decide where their products get placed. Supermarkets also allow these huge corporations to dictate where smaller brands should go as well. This means that a lot of smaller food suppliers aren’t getting a chance to compete because they aren’t getting spots where shoppers will notice them.

Buying in H Mart

Shopping in the ethnic aisle can be extremely limiting anyway. Sometimes, one needs more than a couple of options for fish sauce. Bigger chains like 99 Ranch or H Mart service Asian groceries as well as Patel Brothers, which supplies South Asian products, and Bodega Latina, which specializes in Hispanic foods. These so-called ethnic or international supermarkets bring in $49 billion a year in the US, a huge chunk of the 765 billion-dollar grocery industry. These stores operate differently. They sell to a niche population and cater to their customer’s sometimes extremely specific needs. And they don’t have to worry as much about explaining their culture to customers who don’t know what’s up.

Ethnic aisles continue to change, but they have not gone away completely, and it’s still where you can usually find products like Joyce Chen Sauces. After his mom passed away in 1994, Stephen took over that part of the company while his sister kept Joyce’s cookware business going. A few years back, Stephen started making YouTube videos, explaining how to use Joyce Chen sauces. He wanted to teach his audience about Chinese cooking, just like his mom did.

Comments (5)

Share

I spent a couple of weeks on the USCG cutter EAGLE in 2013, and was amused to see that the mess table condiments included siracha on every table.

I got to visit Jungle Jim’s International market in Cincinnati, and wish we had one in my area. It’s half traditional supermarket, half international market with a pinch of Chuck E. Cheese thrown in. Instead of an international aisle, they give whole aisles to each country or region, as well as having a much more varied meat section, and probably the largest cheese section I’ve ever seen. It’s still not as comprehensive as going to an Asian Market for Asian products, for instance, but it’s so much broader than any grocery I’ve ever seen.

Atlas Obscura: https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/jungle-jims-international-market

When I started working at a Canadian A&P in the 1980s we had a small American foods section. There were products like Jiffy corn muffin mix, Pacman cereal, oyster crackers, clam juice, grits and Bruce’s canned sweet potatoes – alll products that arent normally available in Canada, even two hours from the border. They were imported by a company in Windsor, Ontario which would add stickers to the packages to comply with Canadian labeling laws.

If you ask most people how grocery stores make money, you’d probably say “selling groceries”. That would be wrong. I knew an executive at a large grocery chain who told me only half jokingly that if possible, they’d keep the customers out. Customers make a mess, they put things in the wrong place, and demand attention. Then you have to hire people to clean up after them. If they could keep customers out of the store, they’d be very happy.

Grocery chains make money by selling shelf space, making calendar deals (that’s where one company like Coca Cola can have a sale and Pepsi can’t), and doing advertising promotional deals. And, they don’t use their own employees to stock the shelves. They make the companies that sell the goods do that. They also sell your information via those member cards. They don’t make much money actually selling goods. There’s not much profit in groceries.

Also, they don’t put their most popular products at eye level. People are going to buy Crisco Oil anyway. You put the items people are looking for on the lower shelves, then put the more premium items at eye level. Someone comes in looking for canola oil for salad dressing, and will see that pretty bottle of olive oil, and buy that instead.

By the way, email addresses can end in *.name. It’s been a valid Internet domain since 1998, so please fix it, so it’ll accept my actual email address rather than the backup I keep for websites that still insist that the 10,000 valid Internet domains are not “real”.

For what its worth, Publix has “British Foods” in their international isle