Photographer Ibarionex Perello recalls how school picture day would go back in the 1970s at the Catholic school he attended in South Los Angeles. He recalls that kids would file into the school auditorium in matching uniforms. They’d sit on a stool, the photographer would snap a couple images, and that would be it.

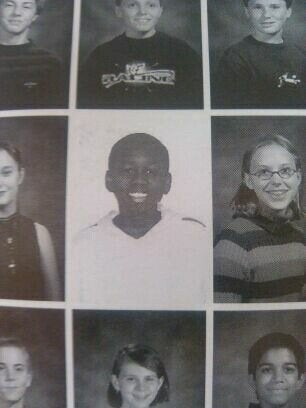

But when the pictures came back weeks later, Perello always noticed that the kids with lighter skin tones looked better — or at least more like themselves. Those with darker skin tones looked to be hidden in shadows. That experience stuck with him, but he didn’t realize why this was happening until later in his life.

When Perello got older, he learned to use a camera. And he realized that capturing images of people with darker skin tones posed certain technical challenges. Sometimes Perello felt as if he had to work against the limitations actually built into the camera and the film. And that’s because, even if we think of the camera as a neutral technology, it is not. In the vast spectrum of human colors, photographic tools and practices tend to prioritize the lighter end of that range. And that bias has been there since the very beginning.

When Perello got older, he learned to use a camera. And he realized that capturing images of people with darker skin tones posed certain technical challenges. Sometimes Perello felt as if he had to work against the limitations actually built into the camera and the film. And that’s because, even if we think of the camera as a neutral technology, it is not. In the vast spectrum of human colors, photographic tools and practices tend to prioritize the lighter end of that range. And that bias has been there since the very beginning.

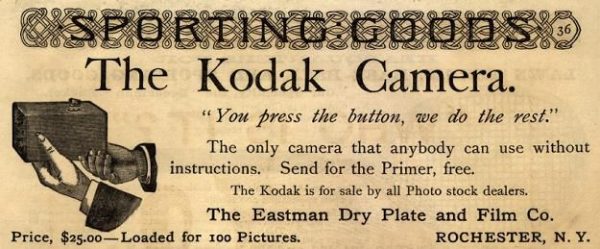

In 1888, George Eastman introduced a camera that revolutionized photography, making it accessible to thousands of amateurs. Kodak simplified the camera and offered to process film for the consumer. One of the company’s early advertising slogans was: “You press the button, we do the rest.” Kodak quickly grew into the biggest player in the industry. The company became almost synonymous with photography itself — like the Kleenex of cameras.

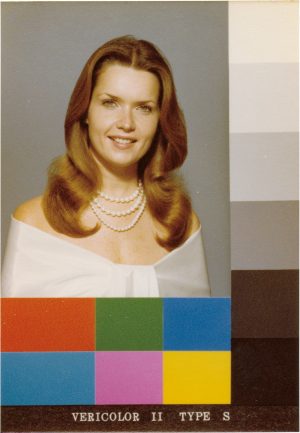

To meet the booming demand for photo processing and printing services, one hour photo labs popped up all over the country. And Kodak supplied a lot of those labs with printers. Each Kodak printer needed to be calibrated and standardized before photos were printed on it. And so the printers came with something called a “Shirley Card,” which was a color reference card created by Kodak in the 1950s. The original one had some color swatches and a picture of a white woman named Shirley Page, who worked as a Kodak employee at the time.

To meet the booming demand for photo processing and printing services, one hour photo labs popped up all over the country. And Kodak supplied a lot of those labs with printers. Each Kodak printer needed to be calibrated and standardized before photos were printed on it. And so the printers came with something called a “Shirley Card,” which was a color reference card created by Kodak in the 1950s. The original one had some color swatches and a picture of a white woman named Shirley Page, who worked as a Kodak employee at the time.

Kodak would ship printed Shirley cards to photo labs across the country, along with the film negatives needed to print the same image. Lab technicians processed the film, printed it, and ended up with multiple test prints. This allowed them to compare the Shirley card printed at Kodak with the Shirley cards printed in their lab. If something didn’t look right with the colors, they’d adjust. Once the printers were set, they’d start feeding film into the machines.

As time went on, Kodak began including other women on the cards, not just Shirley Page, but the name ‘Shirley Card’ stuck. Also, these new Shirleys all shared a common trait: they were all white, which meant that the printers were effectively set for white skin. And Shirley was basically used to calibrate every printer, every time, regardless of the color of the people in the actual photographs being printed. To get accurate prints of a person with darker skin you might have to adjust the printer settings. But that just wasn’t happening at most one hour photo labs. They weren’t about customized service. They were about being fast, standardized, and relatively cheap.

But way that photography prioritizes white skin goes beyond the role of the Shirley cards. If that were the only problem, it would be relatively easy to fix.

Instead, issues can start much earlier in the process, including with the lighting and camera settings used to capture the picture. Take, for example, Ibarionex Perello’s disastrous school picture day — they set a neutral value for exposure early in the day and used it for everyone, effectively prioritizing pictures of students with lighter skin tones. Even if the photographer had finessed the lighting and camera settings with a range of skin tones in mind — there would still be another problem: the film itself, which was optimized for white skin.

If you imagine light as a gradient from black to white, there’s only a small chunk of that gradient that’s visible to a camera. “Dynamic range” describes the width of that chunk that a camera sees. The wider the range, the more tones the film is able to capture, the more accurate the image. But historically consumer film — like the kind made by Kodak — was pretty limited.

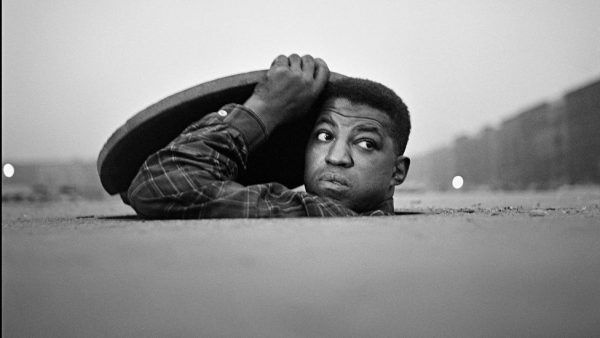

Those who have experience making pictures of people with darker skin tones know how to compensate for all these limitations in the technology. They know they need to change the shutter speed, open up the lens, or use a flash. Photographers like Gordon Parks have made amazing and indelible images of Black life, using the tools available to them. But that’s because they cared enough to figure out how to do it well. Many photographers just haven’t, resulting in the kind of images Perello remembers from picture day.

And it might seem like a small thing, school picture day. But multiply that experience hundreds of thousands of times — not just with professional portraits but also with home photography. All the birthdays and family gatherings and events where pictures are taken. And think about the impact of not being able to see yourself, quite literally, in those pictures.

Over time, the problems with Kodak’s film became clear. During the 1950s and 60s, as schools in the U.S. began to integrate, Black and white kids were increasingly photographed side by side in yearbooks. And parents of Black kids started noticing the way that their kids didn’t look right in those images.

Kodak was slow to adapt, but eventually did — not because they were listening to the complaints from people of color. Rather, Kodak changed their film because they were going to lose the business of two big professional clients: a chocolate company, and a furniture company. Again, it was a dynamic range issue. According to Earl Kage, the former manager of Kodak Research studios, the company had never even considered how expanding the dynamic range of their film would also improve how dark skin tones show up.

By the 80s, Kodak made adjustments to their film emulsions, and eventually introduced a product called Gold Max. Gold Max was leaps ahead of earlier Kodak films when it came to color representation — and the company advertised it that way, but without actually acknowledging the bias that had been baked into the film before. As Kodak started becoming more aware of racial bias in color imaging, they also introduced a multiracial Shirley Card.

Alongside these changes at Kodak, digital photography started to grow. Home photographers transitioned to digital cameras, the dynamic range of which turned out to be much better at capturing darker shades. This made photographing a wide range of people easier than it was in the days of film. Digital photography also spelled an end for one-hour photo labs, and Shirley cards along with them. Home photographers could now take and edit photos without the bias built into Kodak’s early film and printing processes.

But even though the technology of today is way better than the technology of the 1960s and 70s, there is still a lot of cultural inertia preventing dark skin from being photographed in compelling ways. Photography — and cinematography — isn’t just about the film used or the digital sensor in your camera or the techniques used to process your images. It’s also about lighting and staging and all these other elements. In other words, photography is still all about choices. And, in many ways, people still stumble when creating images of darker skin.

Nowadays, it’s much less the technology we’re working against when it comes to accurate representation in images. It’s the users of the technology and the institutions around them, that shape the images we see. Even if Kodak’s early promise was total ease — “you press the button, we do the rest” — the technology will never achieve point-and-click perfection. Because no technology is ever neutral. There will always be choices, and trade-offs and aesthetic judgments. The camera is an amazing tool, but creating a beautiful image…that part is up to us.

Comments (8)

Share

I worked for Xerox for 13 years or as it is known to employees, Fuji Xerox. I learned that Fuji film in the blue and green package was more sensitive to cool colors like blue and green. Kodak film in the orange and red and yellow package was more sensitive to the warm colors. I would think about this when buying film which we don’t do anymore. Just found it interesting that not many people know this.

Nial Connolly

Hi Roman

This also reminded me of my uncle that photographed graduate students when they graduated. His company was contracted to snap a photo on multiple places as the graduates entered and exited the ceremony. (the show must go on). So he told me he used two Nikon film cameras for each scene that needed to be set up. There could be 2-4 scenes at an event. The 1st camera was set up for each scene’s dual-camera setup, as you possibly could guess for lighter skin tones and the second for darker skin tones. Each scene’s camera was then fired as needed to accommodate each students skin tone. You would lose this contact and possibly other contracts in this stressful business if you got it wrong. – He is now retired but was a wonderful experience to see the back office side of the business operating in South Africa.

Some of the things in this article are region locked, unfortunately :( A new inclusivity issue for films and photos!

How the world has changed: I remember going to get photos developed, and being so excited to see how they turned out, when you picked them up a week later (I live in rural Australia, one hour photo was more a city-based phenomenon). Sometimes you wouldn’t remember what you had photographed, and it was a surprise. Nothing like digital photos today. It’s important, and interesting, to realise that the photos we took were also a case of white privelege.

A missed connection in this story are the more recent critiques of face detection algorithms, which are also biased against people with darker skin. Perhaps a topic for a follow-up?

What about photographic challenges on the other end of the spectrum? How did photographers manage extremely light-skinned subjects like Edgar and Johnny Winter?

All stories of history are a picked path. What you report is a set of points connected as seen through and organized by an ideology centered in contemporary American dialogues of race, but it is a partial story and glosses the central idea of camera metering in photographic exposure and decisions made in camera manufacturing (as opposed to film manufacturing which you report on). Overall, the reporting creates an outsized sense of race as a primary element in photographic technical history and photographic exposure bias.

The Shirley Cards are one issue and I agree with the reporting, but the reporting on the technical side of cameras is problematic by omitting a major part of the conversion.

Film captures a dynamic range that is much less wide than the human eye is capable of – as you mention in the story.

Cameras are pointed at everything, obviously, from still lives to landscapes to urban spaces as well as people. In an average photograph, we see a tonal range where there are few pure whites and pure blacks, and a bell curve of tones in the middle. To get the widest range of these scenes to expose correctly you would want to manufacture a camera to meter to a neutral gray, no?

Those that have photographed a bright white sand beach and seen the resulting photograph underexpose or a night scene and seen it overexpose are encountering the limits of a set of decisions made in camera manufacturing. This unfortunately means skin tones at the ends of the spectrum are also incorrectly read when metered automatically and an underpaid or undertrained school photographer isn’t going to adjust manually to every student.

This is a regrettable consequence of a logical set of decisions in camera manufacturing.

The reporting fails to establish a broader frame that includes how cameras are designed and see the world that would help explain the issues reported, and the story needed to be much clearer about the difference between the true bias in Shirley cards and the unintended problems with skin tones on the ends of the dynamic range spectrum caused by an unracialized set of decisions around camera manufacturing and light metering. They’ve been smeared together for the sake of a good story in line with contemporary narratives instead of prioritizing accuracy.

Your reply reminded me about the use of the Gray Card https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gray_card

Back in the day, meters were often used to measure the light and the use of a Gray Card helped the photographer produce an image that was true to the colors and light that the human eye saw. My husband would be able to explain the gray card much better. He was a commercial photographer for 30 years. So in many cases, a poorly lighted subject is partly inexperience on the part of the photographer and limitations of the film and camera used. Plus the processing of the film.

Hey guys, love your work.

But I’m curious… Google Pixel is now pushing adverts referencing the Shirley Card and how their camera was designed for diversity, yah yah yah.

Curious whether you started this conversation, or did they? Please don’t disappoint me!