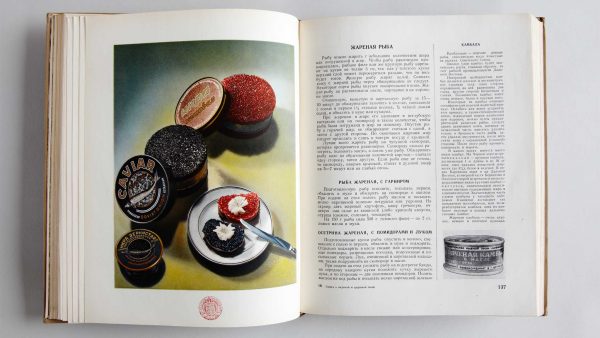

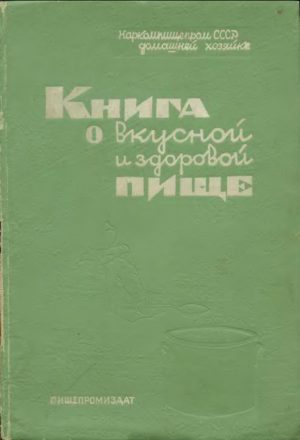

Officially titled The Book of Tasty and Healthy Food, it was often known simply as “Kniga” (translated: “book”) because it was one of the only cookbooks to exist in the Soviet Union. The volume is peppered with glossy photographs of really lavish spreads and packed with text as well. There are recipes for lentils and crab salad and how to cook buckwheat nine different ways. But this book was meant to do so much more than show people how to make certain dishes — it’s a Stalinist document aimed at addressing hunger itself in the USSR. “The book” was at the vanguard of a radical Soviet food experiment that, despite its numerous obstacles, transformed Russian cuisine.

Today, what’s usually served in Russian homes and restaurants is Soviet food, dishes that are generously dolloped with ingredients like mayonnaise and dill. But Russian food before the Soviet Union was entirely different and varied considerably on one’s geographical location and place in society.

Czarist Russia had both extreme poverty and extreme opulence, but the vast majority were living on the edge, eating a relatively basic and monotonous diet consisting of things like fermented foods, cabbage soups, plus foraged mushrooms and berries. The aristocracy, meanwhile, was fabulously wealthy and ate accordingly, consuming vast quantities of caviar and borscht with enormous quantities of meat.

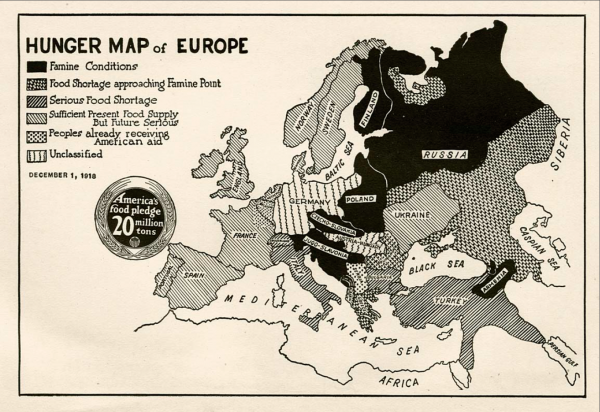

For centuries, that was simply the nature of things. Most Russians subsisted off the land, eating crops when they could and experiencing famine when they couldn’t. Food was a pervasive issue in Russia. During World War I, food riots broke out between merchants and peasants because of high prices and food shortages. These battles of basics like grains and sugars repeated time and time again.

Then, in 1917, revolution swept through Russia, and it gave way to a grand, new state: the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, which was physically massive. The USSR contained a sixth of the world’s land mass, spanned nearly a dozen time zones and over 100 ethnic populations, all of which were supposed to be united under socialism with one constitution, national anthem, and culturally: one cuisine.

New foods, it was decided, were needed to help define the new empire. All ties to aristocracy needed to be broken, and this was part of that effort. Under Lenin, who was Soviet Russia’s first leader, the Bolsheviks were looking for a way to feed everybody, separate themselves from Czarist decadence and ties to fancy sauces and copious amounts of meat, and embrace the modern era. There would be no more foraging to survive or cobbling together old-fashioned recipes in this new Soviet order, but there remained a question: what would replace these traditional approaches? Attempts were made to offer state-run canteens to fill nutritional needs, but these proved problematic. When Lenin died and Stalin took over in the 1920s, the country was starving.

Among other impacts, Stalin’s forced collectivization policies resulted in starving the countryside to feed the cities. At times, organized teams of police would break into peasant households and take everything edible. All this led to a major Soviet famine which killed at least 5 million people, mostly across Ukraine and Kazakhstan. Hungry peasants roamed the countryside, desperately searching for anything to eat. Corpses piled up along the roads. It became clear that Stalin’s policies were pushing the country deeper into crisis, and he desperately needed to turn things around. Where Lenin had promised basics like land, peace and bread, Stalin looked beyond the basics, believing that people needed more than survival to give them faith in the Soviet Union. Food needed to not just fulfill caloric needs but also provide joy.

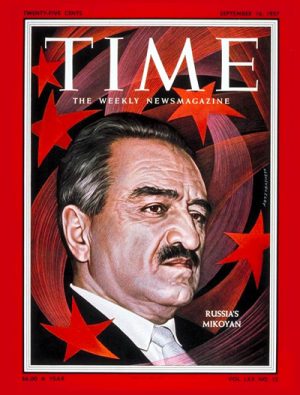

In his quest to create this joyous, indulgent Soviet diet, Stalin decided to enlist the help of a man named Anastas Mikoyan, who he named to be the People’s Commissar of the Food Industry in the 1930s. Mikoyan was a pragmatist but also a dreamer, and above all: he loved food. Stalin tasked him with a seemingly insurmountable problem: figure out how to feed a starving country while also ultimately uniting the Soviet bloc under a new and happy cuisine.

In his quest to create this joyous, indulgent Soviet diet, Stalin decided to enlist the help of a man named Anastas Mikoyan, who he named to be the People’s Commissar of the Food Industry in the 1930s. Mikoyan was a pragmatist but also a dreamer, and above all: he loved food. Stalin tasked him with a seemingly insurmountable problem: figure out how to feed a starving country while also ultimately uniting the Soviet bloc under a new and happy cuisine.

From Mikoyan’s perspective, the solution was obvious. His new cuisine would be cheap, convenient, high-calorie, mass-distributed, and pre-packaged. And for that, naturally, he turned to the most un-Soviet place imaginable: the United States of America. Up until then, Russia’s food production had primarily been small-scale and artisanal. It wasn’t built to feed the masses. Mikoyan, however, was interested in the factory lines that were successfully feeding the workers in America. It wasn’t capitalism but rather the means of production that caught his eye — the same factories, he figured, could be turned toward socialist ends. So Mikoyan traveled to America at the behest of Stalin in 1936, landing in New York and from there touring the rest of the nation.

Ostensibly, Mikoyan’s mission was to buy industrial equipment to be imported by the Soviet Union, but he became fascinated with the whole American food industry, including orange juice and frozen fruits. He visited everything from slaughterhouses to canning factories and studied materials and means of packaging like jars and corrugated cardboard. He marveled at everyday meals involving things Americans took for granted, like hamburgers, which were cheap, filling and convenient: ideal for Soviet workers on the go.

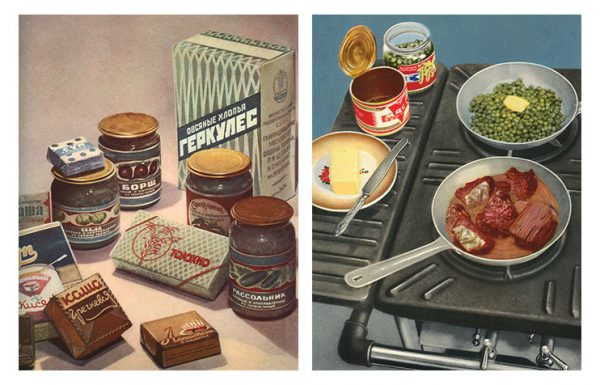

Finally, Mikoyan returned to the Soviet Union and started to build. His new hamburger factory was built to churn out 2 million patties a day. And within a year, Mikoyan’s meat plant (called Mikoyanovski) produced over a hundred kinds of sausages. He oversaw the production of canned fish and corn and peas, cheeses and meats, juices and popcorn, corn flakes and champagne — the list goes on. Then, too, there were condiments, like mayonnaise, which were packed with calories. Eventually, Mikoyan became a household name in the realm of Russian food.

Finally, Mikoyan returned to the Soviet Union and started to build. His new hamburger factory was built to churn out 2 million patties a day. And within a year, Mikoyan’s meat plant (called Mikoyanovski) produced over a hundred kinds of sausages. He oversaw the production of canned fish and corn and peas, cheeses and meats, juices and popcorn, corn flakes and champagne — the list goes on. Then, too, there were condiments, like mayonnaise, which were packed with calories. Eventually, Mikoyan became a household name in the realm of Russian food.

Through it all, Mikoyan was a dogged micromanager. He taste-tested every new product and approved every last label design. To many Russians, he was like some mythical old uncle, a Soviet Chef Boyardee.

Behind the scenes, Mikoyan was hard at work churning out product after product. And since the average Russian rarely left the country because it required special permission from the state, a lot of people had never before seen some of the foods he was mass-producing. But when new things like oranges and hard cheeses and corn flakes arrived, some found it weird, or just didn’t know what to do with them, so part of Mikoyan’s job was to suggest novel uses for this fare.

Mikoyan came to realize that people needed to know about these foods in order to embrace them. They needed to become “cultured” Soviet citizens. And despite all his efforts telling people what to eat and how, it was impossible for him to educate everyone. He needed a new way to reach the masses — a way to spread new methods of preparing and eating meals to over 150 million people. The solution he arrived at in 1939 was a book: The Book of Tasty and Healthy Food. This volume became the official blueprint on how to eat Soviet food.

Mikoyan came to realize that people needed to know about these foods in order to embrace them. They needed to become “cultured” Soviet citizens. And despite all his efforts telling people what to eat and how, it was impossible for him to educate everyone. He needed a new way to reach the masses — a way to spread new methods of preparing and eating meals to over 150 million people. The solution he arrived at in 1939 was a book: The Book of Tasty and Healthy Food. This volume became the official blueprint on how to eat Soviet food.

This new book was spearheaded by Mikoyan and a team of food scientists, offering up nutritional guidelines, advertisements for pre-packaged foods, advice on food storage and table manners, and hundreds of recipes. All told, the book has over 1,400 recipes crammed into its 400 pages.

This publication was pragmatic, but also inspiring, showing tables covered in silver and crystal featuring platters of bread, fruit, chocolate, caviar, the works. Per Stalin’s vision, it highlighted a kind of luxurious optimism. Its sources ranged from America to various Soviet republics, featuring palov from Uzbekistan, borscht from Ukraine, kharcho from Georgia, and more — but the origins were not always disclosed. This was not a book about history but about the future of a unified Soviet cuisine.

Over the years, the book was revised and republished again and again to match the Soviet Union’s changing ideologies. All specific references to a dish being Jewish or American, for example, eventually disappeared. But throughout all the editions, one thing was constant: the book evoked a peculiar optimism. It embodied an almost aggressive cheeriness. And, by the 1950s, it became a staple in people’s homes. With the help of this book and years for it to soak into the culture, Mikoyan’s foods became Russian foods — and many of them evolved away from the cuisines that had inspired them. Hamburgers, for instance, gave way to kotleti, a Soviet staple made up of meat and bread that remains popular to this day. Mass production played a role in what foods flourished as well, including things like ice cream, which citizens would go out to eat even in the dead of freezing Soviet winters.

The book, for its part, didn’t advocate creating one’s own ice cream. Despite featuring ice cream, it advised people to go out and get mass-produced varieties. The point was not so much helping people prepare foods as such but about showing them what foods were out there.

Of course, in reality, food scarcity was still an issue, and many of the idealized spreads found in the book were not realistic for most people. Day to day, people still ate whatever they could find or buy, and for many there weren’t a lot of options. Hunger persisted. Mikoyan’s impressive factories made a lot, but not enough. Grocery store shelves were still often empty, especially outside of big cities. Most of the food, it turned out, had been disappearing into networks of privileged elites, long before it even reached the shelves. Those who befriended others with access, like butchers, could sometimes get treats, like meat. Citizens would carry bags when out of the house on the off chance that the local stores had unexpected foods lining the shelves.

Every cookbook sells a fantasy, of course, but it’s the discrepancy between the abundance on its pages and the absence in the shops that makes this particular volume so jarring. And from a practical perspective, the book’s recipes were often so vague as to be useless, containing instructions like “put meat in oven until cooked.” Serving sizes and preparation times were not its focus.

After the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, there was a lot of hunger and anger again in the region. Many people lost everything. And in the end, the book once again could do little to help with everyday life. For some, though, the foods in this book have become a source of nostalgia, and many of the brands featured in it remain popular to this day.

Comments (10)

Share

The mixture of gratitude and envy to the producer. It’s such a wacky and extravagant book that is also a cultural staple, that yes, it required a foreigner to tell this story. As a proud owner of all sorts of old junk, I am glad someone paid attention to the craziness of this stuff and showed it to the world. As someone who has grown up in the provincial Russian town in 1970-s I confirm the book was perceived a dreamy fairy-tale by the kids; more than two thirds of the products described and pictured in it, was not only unavailable, but unknown to the ordinary Russians. The image of canned asparagus puzzled me for years)). And yes, the mystery of ice-cream in the winter relates to the lack of freezers in the stores and kiosks: ice-cream in the summer was only available in the capitals.

Great Episode! The Netflix show Chef’s Table did a great episode on the current trends in Russian Cuisine and Vladimir Mukhin of White Rabbit Restaurant in Moscow.

I was really curious to listen to this until I figured that the podcast authors call all citizens of USSR Russians and did not even mention that Stalin’s man-made famine was done in order to control Ukrainian and Kazakh population. It was a genocide.

Thank you for saying this, Jul. I had to stop halfway through this episode. Calling former USSR citizens ‘Russians’ is so demeaning, especially considering all of the ways that Russia continues to harm it’s neighboring countries. Using ‘Russia’ as an umbrella term for the former USSR is what makes people believe that Russia still has ownership over places like Ukraine, Kazakhstan, Georgia, etc. I hope this podcast does better research in the future, especially when talking about a genocide.

Please share the name of the ‘what if’ shopping bag. What a fabulous story!

The “what of” bag is called “Avos’ka” and looked like this: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/String_bag?wprov=sfla1

Loved this episode! I have had a copy of “Kniga” since 1985, when I bought it as an exchange student in Leningrad (it’s the 7th edition, from 1980). It’s absolutely terrible as a cookbook—the index is useless, and the instructions (as pointed out) are vague and unhelpful. But it’s invaluable as a sociological study into the way of life of the USSR. I have hundreds of cookbooks and cook from them often, but this is one that I have never cooked from, and probably never will…until maybe now, when it might be an interesting diversion.

At this stage I am really hoping Stitcher will never send you their gingle ahaha.

The photo of the people lining up is actually in Poland. Never a part of USSR officially but under its control. Similar cookbooks were published here.

“Years later, she dusted it off, & handed it to me.” That hit so. hard.

My mom grew up impoverished in nowhere Indiana with Depression-era parents. They made do with what they had, used unripe melons to cool the necks of their sick siblings during summer heat, and made the most delicious meals with what little they had, which wasn’t much, but it fed nine kids. I didn’t grow up with those trials, but my mom still cooked those meals from time to time on special occasions. She passed her recipes and cookbooks down to me just a few years ago.

Now my armpits are spicy and this strange liquid is coming from my eyes. Damn you, 99PI… Why do you have to make me feel my feelings? ;)