The weather can be a simple word or loaded with meaning depending on the context — a humdrum subject of everyday small talk or a stark climactic reality full of existential associations with serious disasters. In his book The Weather Machine, author Andrew Blum discusses these extremes and much in between, taking readers back in time to early weather-predicting aspirations and forward with speculation about the future of forecasting, including potentially dark clouds on the horizon.

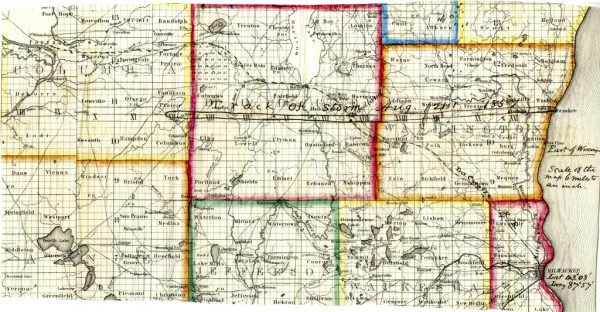

The very idea of forecasting weather across great distances was essentially a non-starter until information was able to travel faster than the weather itself. With faster-than-weather communication systems like telegraphs, the landscape of forecasting was transformed. Suddenly, in the mid-1800s, it became possible to map out phenomena like the paths of hurricanes by relaying data in realtime.

By the 1870s, there was a growing sense that people might be able to model the weather globally. In Norway, physicist and meteorologist Vilhelm Bjerknes began to work on equations for making predictions. His theory was simple: one could make a model, test its predictive power, then adjust the model depending on what weather actually followed. His so-called “Primitive Equations” are still part of weather modeling today, but at the time, he lacked the mathematical tools to actually solve them.

By the 1870s, there was a growing sense that people might be able to model the weather globally. In Norway, physicist and meteorologist Vilhelm Bjerknes began to work on equations for making predictions. His theory was simple: one could make a model, test its predictive power, then adjust the model depending on what weather actually followed. His so-called “Primitive Equations” are still part of weather modeling today, but at the time, he lacked the mathematical tools to actually solve them.

Later, in the 1920s, an English meteorologist by the name of Lewis Fry Richardson followed up on Bjerknes’ work, but calculated it would take 64,000 people working together to produce a useful forecast, meaning one that could be calculated before the actual weather arrived. Essentially, he faced a computational limitation, making the process unfeasible at the time.

Throughout the first half of the 20th century, weather forecasts were indeed created and used, but they were mostly based on general observations rather than rigorous mathematical calculations. When it came to D-Day, for instance, a change in the Allied attack schedule, resulting from a rough two-day forecast, made a big difference in the war effort.

Throughout the first half of the 20th century, weather forecasts were indeed created and used, but they were mostly based on general observations rather than rigorous mathematical calculations. When it came to D-Day, for instance, a change in the Allied attack schedule, resulting from a rough two-day forecast, made a big difference in the war effort.

Finally, in the post-war era, with the rise of space flight and modern computing, more rigorous options became possible. As President Kennedy was making his famous promise to put a man on the moon, he also made a less-remembered call for a global weather forecasting system, making it part of a larger promise about the future of technology that would rely on unprecedented global cooperation.

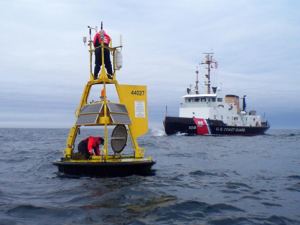

Today, we have forecasts that are more accurate than ever, able to make predictions far in advance. The World Meteorological Organization gathers once every four years to discuss issues and solutions in their much-advanced field. They discuss specific technical challenges as well as big-picture dilemmas, like the rise of private company interest in the forecasting business. With the threat of climate change, there is more at stake and privatized forecasting enterprises are entering the fray.

Today, we have forecasts that are more accurate than ever, able to make predictions far in advance. The World Meteorological Organization gathers once every four years to discuss issues and solutions in their much-advanced field. They discuss specific technical challenges as well as big-picture dilemmas, like the rise of private company interest in the forecasting business. With the threat of climate change, there is more at stake and privatized forecasting enterprises are entering the fray.

After a century and a half of being a service governments provide for their citizens, there is an increasing push for private forecasts. On the one hand, this could improve forecasts, but it could manifest in structural inequalities depending on who can access the best forecasts.

Right now, there’s still a relatively free exchange of weather data between countries, made possible in part through agreements about openness and sharing. If that model changes, though, the impacts could be significant — privately purchased weather data could lead to a sectioning-off of who has access to what information. Good weather forecasting involves data from around the world, and perhaps that fact alone will help encourage governments to keep such data more open.

Comments (1)

Share

Prior to his suggestion of needing 64 000 people for a useful forecast, in 1916 Richardson tried to make a forecast for 7am, May 20, 1910. This six-year-late forecast was intended to be a proof-of-concept obviously. Unfortunately for Richardson, it wasn’t a terribly good forecast. Fortunately, though, the concept itself was valid.

Not sure if this anecdote is in “The Weather Machine”, which I still have to read. (I

found the story in the book “Weather: An Illustrated History: From Cloud Atlases to Climate Change”.)