Nestled between the mountains and the ocean, right next to Santa Barbara, sits Montecito, California. The community is charming and geographically isolated. The landscape is a mix of desert and coast, with soaring hills, natural hot springs, and cool mornings. The hillsides are covered with chaparral, a plant community characterized by scrubby brush, and the neighborhoods are lined with fragrant eucalyptus. But this beautiful landscape is also what makes the area vulnerable to wildfire.

The chaparral covering the hills is fire-resistant for the first twenty years of its life, but as it ages and dries, it becomes rich fire fuel. Then there’s the eucalyptus, which has shaggy bark and flammable oils that can cause the trees to burst into fireballs as they heat up during a wildfire. The slender canyons that sit below the hilltops of Montecito are cozy little spaces where fires can easily take hold. And the community’s so-called “sundowner winds” blow hot, dry air from the desert up and over the mountains and through those canyons.

The region endures a major fire approximately once every 10 years. For this landscape, fire is predictable and it is inevitable. Now, coupled with multi-year drought, it is becoming unmanageable.

For decades, locals have taken fire as a fact of life, rebuilding as needed. But that acceptance is getting harder to sustain as fires become more frequent and more intense — and as communities are forced to reckon with rebuilding again and again. Area residents and officials are starting to rethink how they deal with disaster.

Rebuilding and Rebuilding

In 1964 — the year that reporter Susie Cagle’s father Daryl first moved to Montecito — the Coyote Fire scorched 67,000 acres just north of his mother’s new home. It burned more than a hundred houses and killed one firefighter.

Then, in 1977, the Sycamore Canyon Fire swept through and burned down 250 houses, including Daryl’s. “We got a car full of quickly gathered mementos,” Daryl recalls, “and we drove out and … [the] next morning came back and the house was gone.” Many of the houses that burned had wood shingle roofs, with air gaps in-between where embers could land. In Daryl’s case, the foundation of the house was left, so he and his mother used their fire insurance and rebuilt in the same place.

If there’s an upside to destructive wildfires, it’s that they give a community the chance to redesign. In their aftermath, towns have a rare opportunity to modify the landscape and rebuild houses in ways that will make them more resistant to disasters in the future.

Through the 1950s and 60s, Montecito made a handful of changes to prepare for future fires. The Forest Service tore up some of the flammable chaparral with bulldozers and doused it with herbicide — until fears over toxic chemicals and a growing environmental movement scrapped the project in the 1970s.

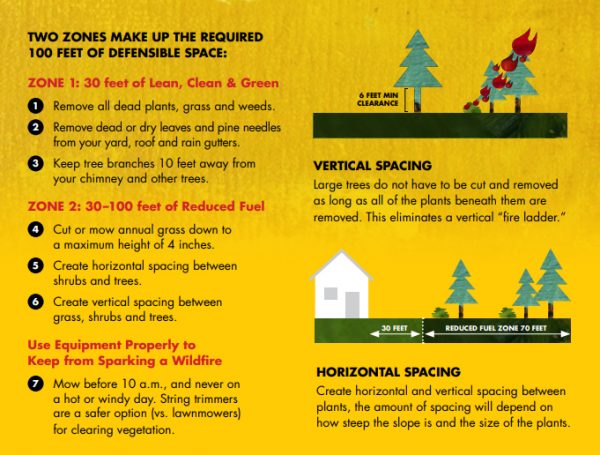

In especially fire-prone neighborhoods, the county began requiring people to build their houses with fire-resistant roofs and walls, and with wide areas of clear, open space around them — what’s known as “defensible space.”

When Daryl Cagle and his mother rebuilt their home, they changed elements of the design. Wood roofs were now banned, so they replaced theirs with concrete, and paved over the tiny surrounding yard. They did what they could to make their space more “defensible.”

But there can be limits to the effectiveness of “defensible space” design, especially in a dense community where people have small yards. “We have neighbors, and neighbors have rights,” explains Daryl, “and neighbors want trees and you can only clear brush from your own land.” So even if someone is diligent about keeping their land carefully maintained, their neighbor might have a propane BBQ, or a tall stand of lovely eucalyptus trees, posing dangers to surrounding homes.

In Montecito, preventing fires can often prove more controversial than rebuilding after them. Prescribed fires set and managed by firefighters were once considered an effective way to burn off fuel — but in coastal California, with its parched chaparral, they’re hardly done anymore. The so-called “controlled” fires can easily grow out of control and destroy valuable ecosystems and neighborhoods.

Then there are ridge-top firebreaks, which are expensive to maintain. These big stretches of cleared land are meant to make space for fire engines, hoses, and hand-tools. They provide firefighters with ready access to the front. But residents of affluent communities don’t like to see big, ugly scars across the lush mountainsides, even when it’s for their own protection.

As communities like this have grown and spread inland, they have gotten closer to what used to be considered wilderness. Many of the people who come to live here from cities are also not familiar with the risks they are taking in the process. Meanwhile, climate change is making wildfires more frequent and intense. It’s a dangerous mix. But the local response to fire damage has stayed remarkably consistent: when a community burns, local authorities rush to issue new building permits. With California in the grips of a housing crisis that has only intensified since the 1970s, it can seem crazier not to rebuild houses, even though the threat of fire is now year-round. There is no fire season anymore.

In 2008, three decades after the Sycamore Canyon Fire, Daryl Cagle’s rebuilt house was threatened again by the Tea Fire. Once again, this blaze burned down hundreds of homes, though this time Daryl’s was spared.

When another fire sparked in the Santa Barbara hills just six months later — the Jesusita Fire — Daryl didn’t really worry about it. Sure, he could see flames in the hills from his house, but they were two canyons over, and everything that could burn between him and the fire had already burned anyway. The constant threat had made him somewhat blasé, like a lot of people in the community.

Fire and Flood

But last year, there was another fire — the largest in California history up to that point — that made people feel a new sense of danger. The Thomas Fire burned through 1,000 homes in cities to the south before the wind moved it north into Montecito.

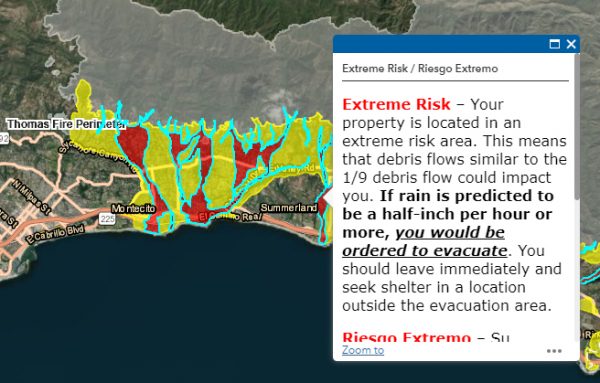

On the morning of December 16, 2017, the fire was raging five blocks away from Daryl’s home. It got so close that at one point, the satellite heat map showed the fire perimeter completely covering his house. It looked on the screen like the house was gone.

The Thomas Fire burned more than 280,000 acres and caused more than two billion dollars in damages. It eventually burned into the still-fresh scars from other recent fires — and without chaparral and other fuel to keep going, it simply put itself out. Only three houses were destroyed in Montecito. People in the town thought they’d been spared. But then the rain came.

In the early morning of January 9th, 2018, a storm pummeled Santa Barbara. A half an inch of rain fell on the mountains above Montecito in just five minutes, causing a devastating debris flow of mud, rocks, and trees to cascade down on the community from above.

The debris flow was a direct result of the Thomas Fire that had burned the mountains just weeks before. After the fire, the waxy substance that coats the chaparral leaves was left as a film across the scorched soil. That oily coating made the ground impervious to water, so rain slipped across it instead of soaking in. And as the rain skimmed across the soil, there was no chaparral to restrain it — the Thomas Fire had devoured all the plants.

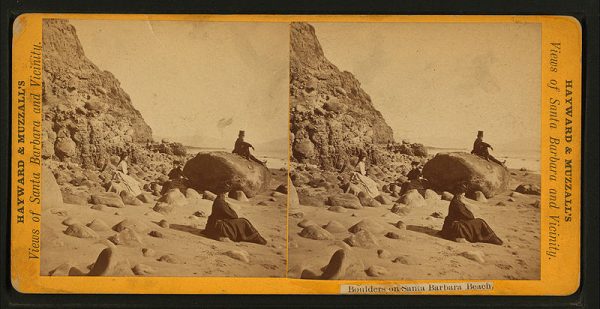

In this landscape, flood is essentially the second stage of fire. Rain came rushing down the hills into the town. As it flowed, the water carried mud, trees, and rocks off the steep hills. Boulders the size of small houses floated down several dense rivers of mud more than 15 feet deep. Some of the debris flows reached speeds up to 30 miles per hour.

Boulders smashed into one house so violently that the gas main exploded. On whole residential blocks, the houses weren’t buried — they were simply gone. More than 400 homes were damaged or destroyed, about a tenth of the whole town. Hundreds of people had to be rescued by helicopter. 23 were killed. Two were never found.

Some of the people whose homes were destroyed in the debris flows have already moved away, or will as soon as their insurance comes through, and their land can be sold. The housing market has cooled somewhat, but Montecito as a whole remains desirable. If anything, the value of every property that wasn’t destroyed by fire or flood in the last year has only gone up.

But where so many fires didn’t change minds about rebuilding, the response to the debris flow has been markedly different, and not just because so many people died.

With the chaparral burnt out of the hills, the whole risk paradigm has changed, as have the engineering challenges. The threat of fire is another 20 years off. The immediate concern now is when the next rain might come and bury the town in mud.

More debris flows are inevitable in Montecito. In fact, they’re how this area was formed, hundreds of thousands of years ago. Debris flows carved the area’s lovely canyons and created its picturesque creeks. Local homeowners had been landscaping around the boulders in their yards for decades, without realizing how they got here — and what they meant about the region. Now geologists are studying the area with a new urgency. They’ve found huge, earth-shifting debris flows as old as 125,000 years and as young as 1,000.

This wasn’t the first time a debris flow had flooded Montecito with a wall of mud and rocks. It’s a regular, repeating cycle that somehow everyone still manages to forget.

Insuring the Inevitable

Debris flows are technically floods, but since they’re caused by fire, California law mandates that they are covered by fire insurance, which everyone in Montecito has. It’s the financial infrastructure that takes over when physical infrastructure fails.

More than government, it’s insurance companies that seem to make the decisions about where and how people can live in California. Insurance companies complain that they’re subsidizing poor, risky decisions, but for the most part, they don’t stop insuring people — they just increase prices, making California an even more exclusive, expensive place to live for everyone.

Local government is mainly empowered to make sure the community is prepared for the inevitable dangers that come with living in such a beautiful, risky place. But as an unincorporated community, Montecito doesn’t have its own political, decision-making bodies, and that’s intentional. The town has voted on incorporation before but it’s never passed. There’s a classic California libertarian streak here, which values personal private property rights alongside tight local community control and support. Without its own dedicated government, most rule-making and infrastructure work are handled by the county.

So far the county has made it pretty easy for Montecito to rebuild. They’ve developed a streamlined review process and are mostly letting homeowners rebuild as they choose.

But now everyone has to build with two threats in mind: fire and flood. People can clear brush from yards, install fire-resistant siding, build concrete roofs, and even buy systems that will shoot flame-retardant goo all over their house. They can close the crawl spaces above their foundation, and lift a house up on pilings. But they can’t make a home impervious to a boulder smashing into it at 30 miles per hour.

The American Institute of Architects is weighing in with design recommendations, and FEMA updated its flood risk maps from 2012 to better account for the hazards that follow a fire. The best the county can do is require people to rebuild within these new guidelines, which call for houses in the newly expanded flood plain to be raised up on elevated foundations or pilings.

Some county officials would actually like to see certain flood-prone neighborhoods stay empty, for the greater good, and they’re considering bolder steps local government could take. Eminent domain would empower the county to take peoples’ homes and land in service of public safety — if the county could come up with the money.

A single lot of land in Montecito can cost more than a million dollars, which makes this strategy challenging. Parcels near creeks would be kept vacant, as memorial parkland, and would act as a buffer — creating more space between future debris flows and homes.

There are other, bigger infrastructure projects that the government could try, that just aren’t available to individual homeowners. Metal nets could be installed on hillsides before large storms, to catch chunks of the mountain before they reach the town. And the eleven existing debris basins in the mountains — which are kind of like dams designed to catch large rocks and trees flooding down the hill — could be expanded and modernized.

But the same people who don’t like the look of fire breaks seem unlikely to embrace stark concrete dams and oversized steel nets marring their beautiful hillsides.

Going to Stay

Daryl wasn’t affected by the January floods, but his house sits right in the middle of a historic debris flow — there’s a creek at the bottom of his steep driveway, and the telltale boulders line his neighbors’ yards. Reporter Susie Cagle showed him the FEMA map that puts him in the red zone, but for Daryl it seems to exist in a separate place from his lived reality. So far, the house has made it through every disaster but one. By his count, those odds are pretty good. Any other evidence just isn’t persuasive.

“It needs to burn down twice for me to get a sense of how often it burns down,” says Daryl. “I mean burning down once … I don’t have enough data points to predict how often it burns down.” This math seems dubious, but part of Daryl’s personal threat appraisal seems to be an assumption that disaster builds character. He likes to say he has a healthier relationship with the stuff he owns because he’s experienced losing everything before. Plus, he asks: with climate change, isn’t every place disaster-prone? At least this place, with all its risks, is comforting and familiar.

“I could move somewhere else in California and have an earthquake,” observes Daryl, or “move somewhere else and have a hurricane take out all of middle of Florida” or “move to Houston and have floods destroy the whole city, then move to New Orleans have floods destroy the whole city.” Or he can stay put and take his chances in a place where his house has so far burned down only once every 57 years.

Comments (5)

Share

Good episode. I was especially interested because I went to high school in Santa Barbara (Laguna Blanca ’71) and remember volunteering to help clear away debris flows in Montecito after a big fire in ’69 or ’70.

Reminds me of this issue in another part of the US.

https://www.npr.org/sections/money/2017/09/29/554603161/episode-797-flood-money?

Maybe we are just systemically hardwired to build in defiance of nature, time and time again.

The Jawbox intro just blew my mind. That was my favorite band when I was a kid and I had just embarked on a youtube Jawbox renaissance a few weeks ago. You were already a 10 in my book…now you are an 11.

Listening to these two episodes about the effects of wildland fire, to people and property who live amongst the wildland urban interface, and then relating it to my 34 years of experience as a firefighter, who worked his way up through the ranks to become a Battalion Chief, Operations Section Chief and Fire Behavior Analyst, I feel I must provide a few additional comments.

Firstly, I feel empathy for those who have had to live through the chaos of a wildland fire as it grinds through their community having also been on the receiving end of a fire in my own neighborhood. I also sympathize for those who have lost loved ones in either the fire, or the subsequent floods and debris flows. Nothing can compare to that loss.

But to the content of the two episodes I feel I must also interject some corrections and suggestions.

While it is obvious to anyone paying attention, fires in the interface areas of California are getting bigger, there’s no doubt about that. But, blaming it on climate change, is a red herring argument. The real causes of larger fires are indeed anthropogenic, but they are the great increase and influx of population in the urban interface, an unwillingness of many residents to take all the necessary mitigating factors to improve their defensible space, the unwillingness of local, and more so state, agencies to enforce those regulations and then follow up with community wide hazard reduction of the intermixed green spaces, the unwillingness of the federal land managers to mitigate the hazards on their “side of the fence” by reducing the fuel loadings (either mechanically or through prescribed burning), the ham stringing of legitimate fuels reduction projects by over-zealous environmental activism and by an increasingly risk adverse fire service. Yes, quite the run-on sentence, but it is a very complicated problem.

Defensible space of individual properties helps immensely.

Fuels reduction projects along interface boundaries and within community green spaces work.

Fuel breaks along ridge lines work. Sorry if they’re unattractive.

Aggressive initial attack works. The urban interface is no place for passive fire tactics, or a “let burn policy”.

I am not a hydrologist, but I don’t think the hydrophobic quality of the soil after an intense fire is cause by residual oils from the chaparral that burned off the slope. I also know that in all but the most adverse situations, debris dams and catch basins work well. I guess the choice is do you want a small disturbance in the viewshed, or a debris flow through your whole neighborhood?

People can live in the interface, if; they take personal responsibility for their property, the public land managers take responsibility for their “property”, the utilities take responsibility for their property, and when disasters strike multiple times in the same footprint, the lights go on for community planners who then prevent the rebuilding of the same problem in the same area. That’s the future design solution.

The last statement of the story isn’t necessarily true.

Move to Michigan.

No major fires, no damaging earthquakes, no debris slides, no hurricanes, no tsunamis, no drought, very low tornado risk, no rising waters flood risk.

Oh, and did I mention unlimited clean fresh water :)

https://www.insurancejournal.com/news/national/2014/09/10/340082.htm