On the night of February 27th, 2010, Luis Enriquez had just gotten home from his job at a lumber factory in Constitución, Chile. At around three o’clock in the morning, Luis started to feel the earth shake. It was an earthquake—a bad one.

With a magnitude of 8.8, the quake that hit Constitución was the second biggest that the world had seen in half a century. The quake and the tsunami it produced completely crushed the town. By the time it was over, more than 500 people were dead, and about 80% of the Constitución’s buildings were ruined.

As part of the relief effort, an architecture firm called Elemental was hired to create a master plan for the city, which included new housing for people displaced in the disaster. But the structures that Elemental delivered were a radical and controversial approach toward housing.

They gave people half of a house.

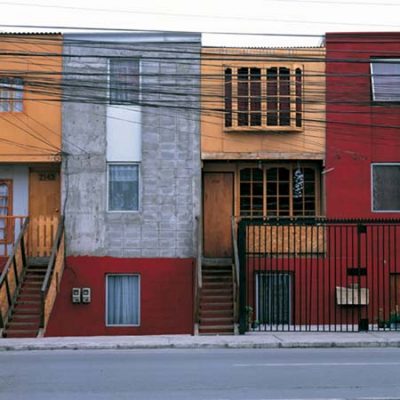

The houses are simple, two-story homes, each with wall that runs down the middle, splitting the house in two. One side of the house is ready to be moved into. The other side is just a frame around empty space, waiting to be built out by the occupant.

Elemental has made a name for itself building these half-a-homes, and not just as disaster relief. The response from the architectural community has been overwhelmingly positive. In 2016, the firm’s founder, Alejandro Aravena, was awarded the Pritzker Prize, one of the top prizes in the field.

These half-built houses are a unique response from urban planners to the housing deficit in cities around the world. The approach has its roots in a building methodology made popular by the 1972 essay, “Housing as a Verb,” by architect John F.C. Turner. Turner made the case that housing ought not be a static unit that is packaged and handed over to people. Rather, housing should be conceived of as an ongoing project wherein residents are co-creators.

Turner and other advocates of this approach, called “sites and services,” began doing building projects where they would work with governments (and/or private partners) to build the parts of housing that residents have the hardest time building on their own—things like concrete foundations, plumbing, and electrical wiring. Governments would also provide services—such as roads, drainage sewers, garbage collection, and schools—to the site.

Over time, residents would turn the component parts of their basic sites into suitable housing, on their own terms. They donate their labor and pay the cost of materials to finish the house. In the end, they own what they build.

In 2002, Elemental received a commission to build 100 units of low-income housing in the city of Iquique, Chile. Their budget was $7,500 per unit. The community was adamant that they did not want large high-rise style public-housing, and even threatened a hunger strike that type of housing was provided.

So, Elemental chose to build half-houses—tall rectangular units separated by empty space. Each one was just big enough to meet Chile’s minimum standards for low-income housing. Then residents on their own time would expand into the adjacent empty space.

Elemental spent the next few years iterating on this concept, and then in 2012, after the earthquake in Constitución, they received a commission to help create a masterplan for the city, which included creating a new neighborhood full of these incremental buildings.

Located on a high hill above the town, Ville Verde is made up of neat rows of houses, with half of each house identical, and the other half completely different. When people got their house, much was unfinished. The drywall was unpainted, the floors unfinished. Kitchens came with just a sink—no refrigerator, stove or cabinets.

Villa Verde resident Luis Enriquez worked first on making his house bigger. With help from his wife and brother—plus workshops and manuals provided by Elemental—Luis laid concrete on the empty side of the house and put up exterior walls, and flooring for the second story. His house was now big enough to comfortably accommodate his family.

Would such an approach work in the United States? Jennifer Stoloff, an expert in evaluating government housing programs sees an alignment with the American ethos of “pulling yourself up by your bootstraps” but also many risks, including litigation issues related to safety.

The biggest hurdle to an incremental building project working in the U.S. isn’t a matter of safety or legality, however. Stoloff believes the U.S. would view it as “an embarrassment.” Even though we might end up providing more people with adequate housing, “we couldn’t do it—we’d lose face,” says Stoloff.

In Chile, these projects have grown out of a culture of scarcity. But even with more money, the builders at Elemental believe that their approach would not change. With a bigger budget, they’d choose to spend money the public space surrounding the neighborhood. And this is at the heart of the sites and services approach—improving the community, and letting home owners invest in and improve on their homes.

Comments (9)

Share

This kind of topic is where 99% Invisible truly shines! More design and architecture please!

Really thought-provoking episode. Goes beyond architecture and into philosophy and ideology.

Great episode – Thanks Roman!

I love this episode! Thanks for sharing this knowledge! This got me thinking about how choice is so limited in the type of housing you can purchase here in the US, even with low-income housing aside. My husband and I got a steal on a tiny little fixer upper in a neighborhood near a wonderful park and have been building the other “half” of our house ever since we moved in. The act of adding onto and fixing the house ourselves has really rooted us in this property and neighborhood. As your episode hints, I think this is a benefit that is hard to quantify. Unfortunately it seems that a vast majority of urban houses on the market today are either way over priced for this type of piece meal ownership/development or have already been torn down and replaced with maxed-out huge new houses which means that the average person can’t afford them anyway. There’s got to be a middle ground somewhere.

In “The Mystery of Capital”, Peruvian economist Hernando de Soto explains why housing in some poor countries is an asset of increasing value to its poor residents, while in other countries the same types of housing deteriorates. It is the stability of clear and enforceable title to their houses that encourages some to improve their houses, while those who cannot have confidence in keeping their houses allow them to deteriorate. These half-houses can only function as they do when the government has a system to protect the residents’ ownership. Otherwise, why improve them? De Soto’s book is short, based on careful societal comparisons of housing development, and easy for a layman to understand. It’s a very worthwhile book to read, if you care to learn how people can get out of poverty in even very poor nations.

There are projects like this in the United States.

Rather than building half of a house and then expecting the resident to finish the other half, the resident helps build the entire house. The entire house is designed, there are licensed contractors working on the house throughout the entire process. The future owners/residents are required to put in a certain number of ours of labor each week to help build the houses.

The company I work for, Structural Design Group, did the structural designs for some of these houses that were recently finished in Santa Rosa, CA. http://www.catalinatownhomes.com/

This is so great. It reminds me of Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Litte House series. The house in which she spends the last few years with her family before marrying is half a house. Her father finishes it after she moves out, I think.

Great episode! In the US a version of this was implemented when towns like Levittown were constructed. The first floor of the house was “finished” while the second floor was left completely unfinished. There were stairs, but it was up to the residents to expand into the upper space.

Another excellent North American example is the Grow Home, developed in Quebec. More than 10,000 units have been built since 1990 by the private sector, with the cooperation of municipalities and other levels of government. The key basic idea is the creation of a fully enclosed shell with minimal interior improvements – kitchen / bathroom on the same wet wall – and freedom given to the home owner as to how the interior space gets divided up. I would like to believe the former HUD employee was simply being argumentative when she said ideas like this could never happen in the US. Some Grow Homes have even been built in the US, as noted on this website:

Link: https://www.world-habitat.org/world-habitat-awards/winners-and-finalists/the-grow-home-montreal/#award-content