In the 1980s, the United States experienced a refugee crisis. Thousands of Central Americans were fleeing civil wars in El Salvador and Guatemala, traveling north through Mexico, and crossing the border into the U.S. [Note: Just tuning in? Listen to the previous episode below.]

In response to this mass migration, a network of churches across the country declared themselves “sanctuaries,” offering shelter to Central Americans who were threatened with deportation and in some cases helping to smuggle people across the border. Leaders and members of these sanctuary churches believed they had a religious imperative to help people fleeing persecution.

The government, however, wasn’t swayed by the religious motivations of participating churches. In 1984, the INS (Immigration and Naturalization Service), a predecessor to ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement), launched a full-scale investigation into the sanctuary movement.

Their goal was to collect enough evidence to indict the leaders of the movement and to stop churches from sheltering migrants. The government believed that sanctuary volunteers were using religion as a cover to push a radical political agenda and to undermine immigration laws. INS decided to investigate the sanctuary movement using the same tactics they might use against any criminal smuggling enterprise. To this end, they enlisted undercover agents to infiltrate and gather evidence.

The main undercover informants were named Jesus Cruz and Salomon Graham. Both were former smugglers who had been caught bringing undocumented people across the border. They agreed to work with the INS in exchange for payment and for having the charges against them dropped.

Cruz and Graham, along with a couple of other agents, spent ten months undercover. Their methods would eventually come under public scrutiny, because they had not just infiltrated the sanctuary movement— they were also secretly recording meetings, conversations, and in some cases, church services.

In January 1985, sixteen leaders of the sanctuary movement were indicted, including Jim Corbett and Reverend John Fife, the two founders of the movement, as well as a number of other priests, nuns, and congregants. They were charged with multiple counts of conspiracy to violate federal law as well as harboring, transporting, aiding, and abetting illegal aliens.

The sanctuary leaders assembled a team of lawyers to assist in their defense. Attorneys chose two primary arguments to defend the sanctuary movement.

The first argument stemmed from religion. Many religions have a distinct imperative to assist people who are fleeing some form of violence and oppression. The defense planned to argue that the sanctuary workers were merely acting in accordance with their faith. They also believed the religious rights of the sanctuary workers had been violated by the government agents who’d infiltrated their churches and made secret recordings.

The second part of the defense’s argument revolved around the legal framework of asylum. The law provides that people fleeing certain specific kinds of oppression or violence have a right to asylum.

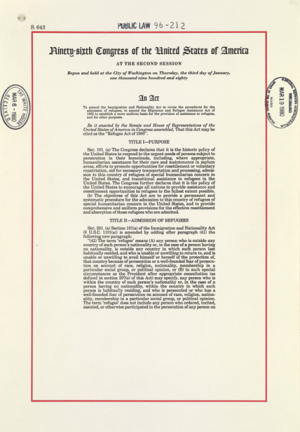

This was all happening in the context of a major shift in U.S. refugee policy. Before 1980, the U.S. approach to taking in refugees had been expressly political. It gave preference to refugees fleeing communist countries and countries in the Middle East. In 1980, President Jimmy Carter signed the Refugee Act of 1980 into law. This legislation was supposed to create a more equitable system by adopting a more humanitarian, non-ideological definition of a refugee. It drew on criteria developed by the United Nations, which identified a refugee as anyone with a well-founded fear of persecution based on race, religion, nationality, social group or political opinion.

Even though this new criteria was in place when President Ronald Reagan came into office, the lawyers for the sanctuary movement believed the government was not following its own law. They thought INS was turning away large numbers of Salvadorans and Guatemalans who should have qualified as refugees. Between 1983 and 1986, the approval rate for Salvadorans and Guatemalans seeking asylum was under 3 percent. The defense attorneys for the sanctuary movement organizers felt like they had a strong case to make against the U.S. government.

But the defense’s entire legal position was wiped out when the federal judge hearing the case ruled that they were prohibited from saying anything during the trial about a number of subjects: United States refugee law, international refugee law, conditions in El Salvador, conditions in Guatemala, or religious faith.

The prosecutor and judge had effectively reduced the case to a simple yes-or-no issue: had the sanctuary workers engaged in a conspiracy to smuggle undocumented people into the country? There was to be no discussion about context, history or motivations.

Over the next several months, the prosecution laid out its case, relying heavily on testimony from their undercover informants. The defense team tried to undermine those accounts in cross-examination, raising questions about context and motivation when they could. But when it came time for them to present a case, they rested, without bringing any witnesses to the stand.

The jury deliberated for more than 48 hours across the span of nine days. On May 1, 1986, six months after the start of the trial, the jury reached a verdict. Three of the sanctuary workers were acquitted of all charges, including Jim Corbett. Eight were found guilty, including Rev. John Fife.

The judge gave out surprisingly lenient sentences. No one got jail time. Everyone who had been convicted got five years probation.

Not long after the criminal trial ended, a group of churches and refugee rights organizations filed a class-action lawsuit against the government. They alleged that the government had engaged in discriminatory treatment of asylum claims made by Guatemalans and Salvadorans. In 1990, the government settled the lawsuit, giving people from these countries temporary protected status and work permits. After this victory, the sanctuary movement started by Rev. Fife and others began to wind down.

But even though the churches were slowing their work, the whole idea of sanctuary was spreading. College campuses, cities, counties, and states began to declare themselves sanctuaries—and not just for refugees fleeing persecution, but for undocumented immigrants more broadly. However, what “sanctuary” actually means varies from place to place and depends on context.

In some places, police aren’t allowed to inquire about a person’s immigration status (or to give that information to the federal government). In other places, all residents are promised access to city services regardless of their immigration status.

President Donald Trump talked a lot about “sanctuary cities” during his campaign and has pointed to murders committed by undocumented immigrants as evidence that sanctuary cities should not exist. He’s threatened to punish self-declared sanctuary cities by stripping their federal funding and, under his direction, the Department of Homeland Security is gearing up to deport large numbers of undocumented immigrants. In response, churches, local governments, and other institutions are preparing to resist.

In 2011, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement issued a memo saying that some “sensitive locations” including houses of worship, hospitals, and schools require special consideration by immigration officers, meaning the government would not prioritize deporting people from those places. But that practice isn’t codified into law and it could easily change.

Recently, there have been reports of ICE agents targeting undocumented people in places like hospitals and schools. Churches might also be vulnerable. It remains to be seen what role institutions and municipalities will play in the coming years, tangled up in an issue that will almost certainly land back in the courts.

99% Allusional

Join Roman Mars and Helen Zalzman live in Los Angeles on Friday, April 14th for 99% Allusional: Objects and Words for Beautiful Nerds. This special portmanSHOW of 99pi and The Allusionist is an Arts for LA fundraiser to support local creatives. Click here for tickets.

Meanwhile, The Allusionist has a new episode about the meaning of “sanctuary” — though we now associate the term with safety for the persecuted, it has an even longer history of referring to something rather different: refuge for criminals. Click here to listen.

Comments (7)

Share

I’m happy to see this movement gaining momentum. Freedom of Movement or the Right to Travel is a fundamental human right. Yes, there are arguments to be made about restricting immigration, but unless the person is a criminal or a danger to the public, there should be very few or no limitations as to who can enter or leave any country.

Those looking to move and work in order to better provide for themselves or their families should be free to do so and are almost always beneficial to their host nations.

In an ill-conceived effort to be ultra-topical or “relevant”, 99% Invisible becomes a poor man’s ‘This American Life’. The issue is important, but there are a hundred other sources far better suited to tackle this. Go back to your original remit. You want to do a story about sanctuary? Fine, but at least tie it back to design. Give us a story about hiding holes used by the Underground Railroad, or priest holes, or the innovations used by refugees to move undetected over borders. Don’t give us a weak collage of interviews.

Have to agree here. I subscribed to 99pi for the particular emphasis on design, and that’s what interested me, but there have been an increase of stories lately that lack this distinction. At least when Planet Money covered immigration, they tied it back to their main premise (economics).

Excellent quality as always, but a bit too far off topic for my taste.

This planet is overpopulated by humans. That over population decimates almost all natural resources throughout the world, which is already causing a mass extinction of all types of life. The more people you help survive the more burden you place on our planet.

There is a cost for everything, including well intentioned humanitarian aid. Almost every action has an equal or opposite reaction. Example: Help a refugee family of 10 and kill countless plants, animals, micro-organisms, etc. over the next few centuries as that family multiplies and consumes.

What is more important to you? Helping people now or preserving a habitat for generations to come in the near and distant future.

Humanitarian aid is vital but there seems to be no long term assessment of that aid from the people who are most influential in the pursuit of helping humans.

I am quite apalled reading some of the comments under these last two episodes. 99pi has had quite a few episodes dealing with history and other topics not directly related to design and architecture. If you are not interested in one, move along. It’s what I do.

Law and language are tools to design a society. Sanctuary is tool to design society.