Chindogu by Vivian Le

Everyone understands the struggle of being away from a power outlet and having a battery for a device die. This would seem like a hopeless situation, but thankfully, there’s a handy, AC-free battery-powered battery charger. All it takes are 12 new batteries to fully charge that one battery of the same type! Useful right? Probably not! But at the same time it’s not entirely … un-useless.

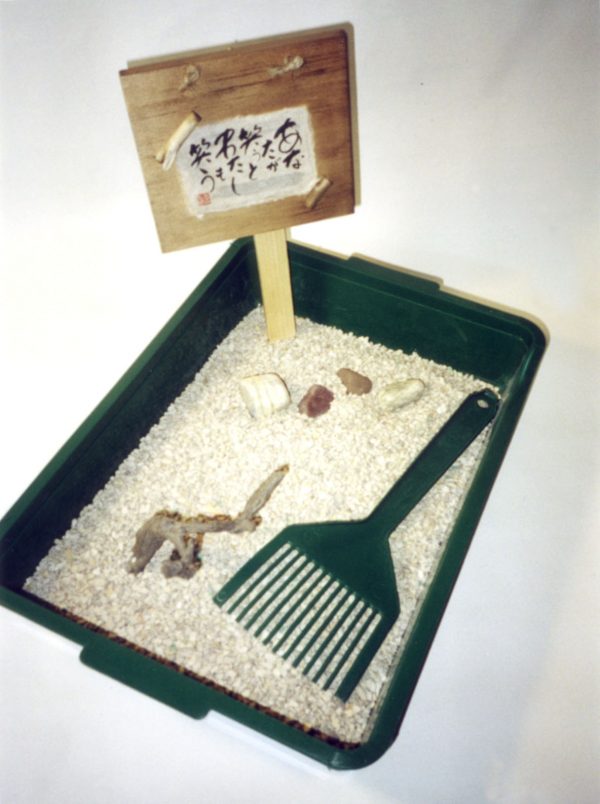

The AC-free battery-powered battery charger is just one example of a chindogu — the art of inventing everyday gadgets that appear to solve a particular problem but are in reality pretty useless. It derives from the Japanese word “chin” meaning “weird,” and “dogu” meaning “tool.” While there are literally thousands of different types of chindogus, other examples include: a solar-powered flashlight, training wheels for high heels, and a zen kitty litter box that would let you practice the art of sand raking while simultaneously cleaning up your cat’s feces.

In the early 1990s Kenji Kawakami was the editor of a Japanese shopping magazine called Mail Order Life. Most of the items in the pages were typical home goods like dishware or electronics, but one month, Kawakami realized he had a few extra blank pages that he needed to fill. Kawakami studied aeronautical engineering in school, and on his spare time enjoyed tinkering with crafts in his workshop. As a joke, he decided to fill the rest of the pages with a few of his un-useless inventions just for fun. This ended up being such a hit with his readers, soon Kawakami was including photos of other chindogus in every issue of the magazine.

Within a few years, an American translator and journalist named Dan Papia came across Kawakami’s chindogu, and thought this concept needed to be shared with the world. Papia believed that chindogu could be an entire movement, with people all over the world building their own prototypes, holding contests, and having fun with it. Kawakami and Papia founded the International Chindogu Society and established ten tenets of the art form:

- A chindogu cannot be for real use.

- A chindogu must exist.

- Inherent in every chindogu is the spirit of anarchy.

- chindogu are tools for everyday life.

- chindogu are not for sale.

- Humor must not be the sole reason for creating chindogu.

- chindogu are not propaganda.

- chindogu are never taboo.

- chindogu cannot be patented.

- chindogu are without prejudice.

Although it might seem a little strange to use absurdist design as a form of anarchy, Kawakami was actually a radical activist in the 1960s and 1970s. You can see elements of this in chindogu themselves — nonconformity and anti-consumerism is something that is rooted in the concept of the movement. These gadgets represent the spirit of creativity and invention without being bogged down by the threat of commercialism. Kawakami and Papia ended up releasing a handful of books featuring chindogus that they had created, or that had been submitted by other members of the International Chindogu Society. But since the fifth tenet dictates that chindogus are not for sale, Kawakami donated much of his money to charity.

Comments (17)

Share

umm, a solar powered flashlight isn’t exactly useless you know…

just in case Viv doesn’t get it, it charges when you don’t need it…

I would agree, especially during natural disasters it can be a pretty handy tool when there’s a mad rush to stock up on batteries.

I agree, especially for those living in areas that are prone to natural disasters such as Hurricanes they can be of great use.

Hello 99 PI,

Articles or principles of a manifesto or a constitution are tenets. Unless these principles are only contract residents of the doctrine, then they may be tenants.

Awesome story on the Prisoner. Go Trufelmans!

Re blue glass: I can’t see a window pane from the street view image, but there is a house in Berkeley that is clearly devoted to blue glass. The architecture looks old enough to me, but you’re the experts. You don’t even need to cross the bridge. Northeast corner of Milvia and Francisco.

The original 1966 yule log footage was found in a can and restored in 2016. Please correct this error.

Regarding the Yule Log segment: the Latin word for hearth is “focus”. Back in the old Roman days, I guess that’s about all there was to focus on sitting around your living room. So maybe it’s not such a stretch to think of a family staring into a fireplace.

Two of your stories in this episode made me feel my age. I watched The Prisoner when it was originally broadcast in the US in the 1960’s. I had seen Patrick McGoohan, the star, in another British series called, Secret Agent Man in the US and Danger Man in Britain. The Prisoner was very weird but I loved it.

Since we lived in New Jersey, we got WPIX, channel 11 and we always watched the Yule Log on Christmas Eve. I probably didn’t see the original log video but we always tried to identify where the loop ended.

You guys are fantastic! Really enjoyed the show! You made my day!!!

There’s a Victorian in SF where one of the apartments on the top level has nothing but blue glass. I’ve always wondered about it! Corner of Fulton and Cole — clearly visible in Google Streetview.

https://goo.gl/maps/3yDhjpdm5AD2

BBC R4 Extra has a radio adaptation of “The Prisoner” in progress: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/m0001f39

And it was a sort of follow-on to McGoohan’s previous series, Danger Man (1960–68; retitled as Secret Agent in the US). That was a actual thriller program.

I grew up with the Yule log. There is a happy addition to the story. The original 1966 footage was discovered. https://pix11.com/2018/12/24/watch-the-wpix-yule-log-and-learn-the-history-of-the-famous-christmas-fireplace/

Love the log. But WPIX wasn’t/isn’t a UHF station. It was Channel 11, home to local kids’ shows (Officer Joe Bolton, Captain Jack McCarthy, Chuck McCann). Home also to The Honeymooners, in years and years of late-night repeats.

Listening to the Yule Log story reminded me of my favorite Christmas music album that our family had when I was young — all the hits by Percy Faith, The Ray Conniff Singers, Mormon Tabernacle Choir…none of the Mariah Carey nonsense.

Did Roman really not know what a Yule Log was?

Today with blue light

“Energy Saved, Sleep Lost: The Unintended Consequences of LED Lighting”

https://medium.com/@caseorganic/energy-saved-sleep-lost-the-unintended-consequences-of-led-lighting-c0909d4872d0

I totally sent you an email about Portmeirion :) Will shamelessly take the credit (pff Vaery’s ancient t-shirt :)) Love the show!